As Nazi power spread across Europe in a terrifying wave, many felt that resistance was futile. A seemingly indomitable and heinous force was devouring the continent, and most of the population — laypersons or clergy — felt that silence was the only option.

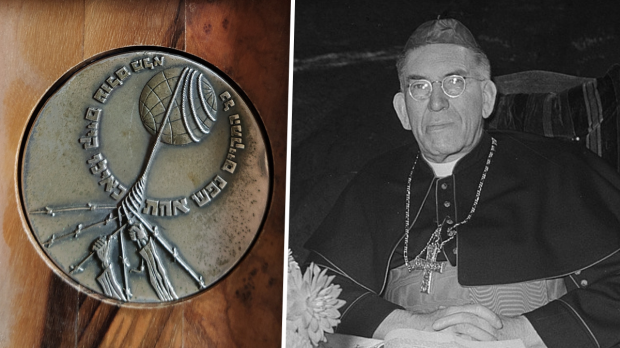

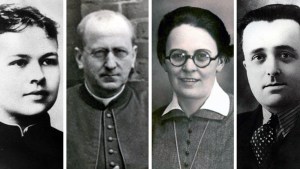

Some individuals, however, chose to operate according to the words “non possumus non loqui” (“We cannot be silent”). Among them was Johannes de Jong, a Dutch cardinal credited for personally saving “hundreds of Jewish families and children.” He has now just received the distinction of “Righteous Among the Nations” — a title Israel bestows on non-Jewish persons who risked their lives to save Jews from the Holocaust.

Johannes de Jong was born in 1885 in a village on a Frisian Island in the northern Netherlands. He was one of nine children (two other brothers ultimately became priests). He attended Rijsenburg Seminary and then the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome, where he earned doctorates in philosophy and theology. He was ordained a priest in 1908.

Aside from his clerical duties, De Jong also served as a professor of Church history. A New York Times article said his students remembered him fondly “for his gentleness as well as his scholarship,” and that he had the demeanor of “the typical ‘absent-minded professor.’”

Consecrated as the Archbishop of Utrecht in 1936, De Jong was coming into prominence at a difficult time. In the much larger, neighboring country of Germany, the national socialist (Nazi) movement had gained a menacing trajectory.

When World War II erupted, the Netherlands maintained an official position of neutrality. In May 1940, the Nazis invaded and occupied the country.

During this period of occupation (which would last until Germany’s surrender in May 1945), De Jong was effective in getting Dutch Catholic trade unions to resist the Nazis, and he firmly maintained that any Dutch Catholics who belonged to Nazi-affiliated organizations would be excluded from the sacraments.

De Jong also wrote letters denouncing the persecution and deportation of the country’s Jewish residents, and he urged other members of clergy to warn the faithful about the dangers of national socialism.

Such activities led to a visit by Gestapo (Nazi secret police) officers, who tried to coerce him into silence. But De Jong would not oblige them.

Shortly after World War II, De Jong was elevated to the cardinalate. He remained a cardinal until his death, following a long illness, on September 8, 1955, two days before he would have reached age 70. The day after his death saw publication of a brief New York Times article mentioning that he resisted the Nazis with “the strength of a valiant personality” and that, “When the Nazis threatened him, he stood firm … and went on doing his duty as he saw it.”