Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

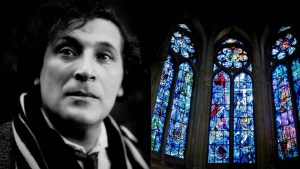

It was Pablo Picasso who famously claimed that, after Henri Matisse’s passing, no other painter had been able to “get color” like Chagall. As Vittoria Traverso explained in her article on Chagall’s stained-glass windows, his “dreamlike style and choice of subjects — love, faith, grief — gave his works a deep-felt humanity that differentiated itself from much of the abstract and intellectual creations of his modernist contemporaries.” In a word, his work was decidedly incarnate.

Visual artist and a psychoanalyst Jennifer A. Swan’s book On the Spirit and the Self: The Religious Art of Marc Chagall, explains Chagall’s place in the history of 20th-century art as a primarily religious artist. In the words of Dr. Murray Stein, author of The Bible as Dream, Swan’s book “has captured the amazing expanse of Marc Chagall’s spiritual vision. This is an artist [Chagall] for our divisive times, a bringer of healing.” In short, Swan’s book explains how Chagall was able to draw from the sources of his own Hasidic Jewish faith and tradition and “translate” it to a “universal” language – that is, he would get to the core of his own religious experience, clarify it, and express it in a symbolically dense yet still accessible-to-all visual language. In that sense, “Chagall was among the most prolific and significant religious communicators of the 20th century.”

The director of the Marc Chagall Biblical Message Museum in Nice (France), Jean-Michel Foray, claimed Chagall was the painter who “restored to art the elements that (most) contemporary artists rejected, such as allegory and narrative — art as comment on life.” This preservation of the role of art as commentary is part of Chagall’s Jewish heritage, Rabbinic literature consisting primarily of collections of biblical commentaries.

In fact, Pope Francis has referred to Chagall’s “White Crucifixion” as one of his favorite of his paintings, highlighting its “narrative” power. In a biography published in 2013, Pope Francis: Conversations With Jorge Bergoglio: His Life in His Own Words, the then-Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio said that the “’White Crucifixion’ by Marc Chagall, who was a Jewish believer, is not cruel, but hopeful […] Pain is depicted there with serenity. To my mind, it’s one of the most beautiful things he painted.”

On Francis’ predilection for this painting, the website of the Diocese of Denver notes that:

“White Crucifixion” was painted in 1938, on the threshold of WWII, after Chagall had become aware of horrific Nazi programs against the Jews. In the painting, a crucified Christ is surrounded by scenes of terror and devastation. Above the cross float three rabbis and a Jewish matriarch, in obvious distress. A man on the lower left flees with the Torah, as on the right we see the Jewish holy book in flames. A man in green flees with his knapsack on his shoulder, while below him a distraught mother cradles her infant – an image reminiscent of so many recent photographs of Syrian and Iraqi refugees fleeing the brutality of a more immediate conflict.

On the left of the canvas is a boat presumably filled with emigrants, while above them a village is upended and in flames, its inhabitants and their belongings scattered amidst the chaos. Though Pope Francis discussed this painting several years ago, it is sadly even more relevant today as the earth currently endures its worst refugee crisis since the Second World War.

Chagall’s Peace Windows

Traverso’s article explains how, in his early seventies, the Russian-born master began to work with stained-glass. “Over the course of 15 years,” Traverso goes on, “Chagall designed iconic glimmering blue windows in both synagogues and churches around Europe that are now known as peace windows.” Having spent much of his life in Catholic France, Chagall was interested in spreading a somewhat “universal” message of peace, love, and tolerance using both Jewish and Christian themes.

“For me a stained-glass window is a transparent partition between my heart and the heart of the world,” Chagall said. “It is something elevating and exhilarating.”