When compared to Late Ancient literature in general, biblical narratives seem to leave much to the reader’s imagination when it comes to describing its main characters. The Bible does not describe, for example, any of the physical features of Moses or David. We only know the former might have been a stutterer (or that he didn’t really speak the same language of the people he was leading through the desert) and that the latter was shorter than Goliath, the giant — which is not much to say, really.

It is true that by looking at some names and learning their etymological meaning, some things can be deciphered. Esau, for example, might mean either “reddish” or “hirsute,” suggesting he was both hairy and, perhaps, a bit of a redhead. Then, surprising as it might be, the Gospels say very little (in fact, almost nothing) about how their main character, Jesus, looked — much less about the appearance of the apostles.

The same goes for Mary, as the scriptures do not provide many details about her appearance either. That’s why artists had to rely, from the very dawn of Christianity, on the artistic canon of their day and age, rather than on the actual written testimony of the early Christian communities, when they sought to portray their Messiah and his mother in icons or frescoes.

One of those artists — tradition holds — is also the author of one of the Gospels. Christian tradition has attributed to Luke many different talents, one of them that of being an exceptional painter, and the author of the very first “portrait” of Mary herself. Considered the most literary of all Gospel writers, he is not only credited with the Gospel According to Luke and the Acts of the Apostles, but Eastern churches consider him the original iconographer, responsible for “writing” the first icon of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

In the Acts of the Apostles, Luke recounts Paul’s shipwreck on Malta in the year 60.This is how Christianity came to this island in the heart of the Mediterranean. Since then — and still today — the Maltese have been among the most passionate Catholics in the world and have a special relationship with the Virgin Mary.

The small archipelago has more than one church per square kilometer (nearly four per square mile), and most are dedicated to Our Lady. Some are known for numerous answered prayers, which have occurred over the centuries. This is confirmed by the numerous votive offerings (“ex-votos”), which are testimonies of miracles received. Here, we share the (miraculous) stories of five of these churches.

Our Lady of the Ruins: Our Lady Tal-Ħerba

In the heart of the old village of Birkirkara, there’s a church dedicated to the Virgin Mary that, even if small, remains among the most well-known and visited shrines in the archipelago. Originally, it was built amid rubble and ruins, probably the origin of the name Our Lady Tal-Ħerba (meaning, approximately, “of the ruins”). In its titular painting, the Virgin is depicted with Jesus in her arms, gazing upon the souls in Purgatory. The date of construction of the original shrine is uncertain, but it was already a well-known Marian destination by the 16th century. In 1615, the bishop of Malta referred to this church as Tal-Ħerba, a shrine dedicated to the Assumption of Mary.

Tal-Ħerba is all about mercy: a flood of graces has inundated the faithful who have prayed to the Blessed Virgin Mary before her image in the small church Tal-Ħerba. Numerous ex-votos are testimonies of these graces received: small paintings donated to the shrine in thanksgiving, depicting the grace received. There are more than 500 ex-votos in the shrine of Our Lady Tal-Ħerba, dating back as early as the late 16th century.

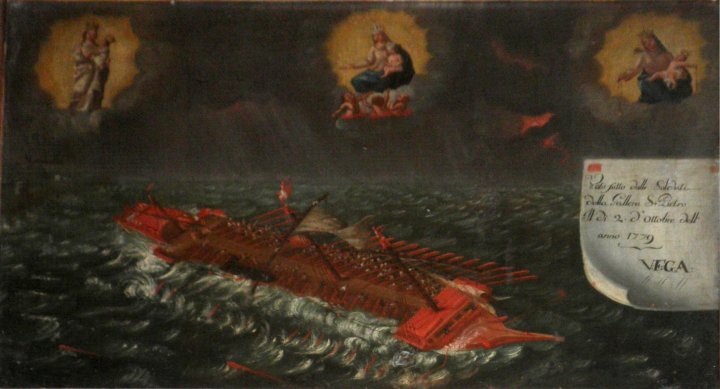

The paintings were commissioned to painters known as “madonnari.” Some are rudimentary and very simple, others more elaborate; some are the gift of individuals, others of groups. Among the most recurrent subjects are those concerning maritime life. Indeed, the Maltese were often employed in navigation, as privateers or in the service of first the Hospitaller Order and then the British Crown. Storms, battles, diseases, and the dangers of navigation are the reasons why these men raised their supplications to the Virgin.

While this type of subject is found in many Marian shrines on the island of Malta, the Tal-Ħerba shrine is also characterized by several ex-votos of women who prayed to the Virgin Mary for a healthy pregnancy and birth after experiencing miscarriage. Many paintings show a woman, often depicted still in bed, with her newborn child, born alive through the Virgin’s intercession, sometimes even with her stillborn child from a previous birth or with her other children gathered around her as she teaches them to pray to Our Lady Tal-Ħerba.

Shrine and Grotto: Our Lady of Mellieħa and Our Lady Tal-Għar

The National Shrine of Our Lady of Mellieħa is the oldest in the Maltese archipelago. It has a long history shrouded in mystery and tradition. One of the oldest traditions has it that the evangelist Luke painted the fresco of Our Lady kept in this shrine during his stay in Malta with St. Paul in the year 60. Another tradition says that some Catholic bishops visited the cave in 409 and consecrated it as a church. Be that as it may, the present icon is of late Sicilian-Byzantine origin, probably dating back to the 13th century. In the following centuries, devotion to the icon increased greatly. Pilgrims here have always asked the Virgin Mary for graces. The numerous ex-votos kept in the sacristy reveal that she was not slow to grant them.

The iconography of the painting reflects the definition of the Council of Ephesus (431) of Mary as Theotokos, as Our Lady carries Jesus in her arms. Restoration work revealed some secrets of the sacred icon: the inscription “MAT DEI,” short for “Mother of God,” and a flower or star on Our Lady’s forehead representing her eternal virginity. The pearl-like details of the two haloes — of Our Lady and Jesus — represent light and brightness, and the dark-colored traces on the Child’s halo, when connected, form a cross within it. The original color of the Virgin Mary’s veil was a strong reddish hue, the imperial color, a symbol of royalty. The shrine at Mellieħa is part of the European Marian Network, which binds together 20 Marian shrines from 20 different nations.

Crossing the road, just below the shrine (about 50 steps down), is the underground crypt of Our Lady Tal-Għar, a 17th-century chapel carved out of the rock thanks to the great love of a Sicilian merchant, Mario de Vasi, a frequent visitor to the shrine of Our Lady of Mellieħa. By his wish, a white statue of Our Lady holding Baby Jesus is also found in the cave. A legend says that the statue was brought from this chapel to the shrine on three different occasions and each time they found it back in its original place in the underground chapel. It has remained there ever since.

A number of miraculous events took place in 1887, 1888 and 1948, all of which are recorded in documents kept in the shrine’s archives: various groups of people, on different days and at different times, gathered in prayer, saw the statue of the Virgin Mary moving her right hand vertically and perpendicularly, making the sign of the cross. Over the years, thousands of pilgrims have visited this underground shrine and prayed to Our Lady tal-Għar, attributing to her many miraculous interventions and healings, both spiritual and temporal. Healing and the birth of a child are among the most frequently requested graces. The walls of the chapel are covered with written testimonies of people who have received the requested grace.

The Three Hail Marys, Our Lady of Ta’ Pinu

The beginnings of devotion to Our Lady Ta’ Pinu are ancient. Before taking the name Ta’ Pinu, the local church was a small chapel dedicated to the Assumption. In 1575, apostolic visitor Msgr. Pietro Dusina, a delegate of Pope Gregory XIII, found it in a very bad state and ordered its demolition. When the demolition began, a worker broke his arm at the first blow: this episode was considered a divine sign and the chapel was not demolished. Ownership of the chapel changed many times, until Pinu Gauci (hence the name, Ta’ Pinu) paid for its restoration and also commissioned the painting of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary for the main altar.

In 1883, this modest, virtually unknown country chapel became the scene of miraculous events. On June 22, while walking past the old chapel, a peasant woman named Carmela Grima heard a woman’s voice inviting her to enter. The same voice asked her to recite the Hail Mary three times. She later described the incident to a friend, Pietro Portelli, and discovered that he too had heard the mysterious voice near the chapel; later, Portelli’s mother (suffering from a serious illness) had miraculously recovered. The news spread quickly and the faithful began to flock to the chapel.

In 1920 work began on today’s shrine, which was opened in 1931. The neo-Romanesque church stands around the old chapel (which has remained intact behind the altar) that still houses the miraculous painting of the Assumption of Our Lady. Today the national shrine of Ta’ Pinu is the most important shrine in the archipelago, a destination for local and foreign pilgrims alike. Many of them return to Ta’ Pinu to give thanks for a grace received: ex-votos literally cover the walls of two rooms near the sacristy. Among them is that of John Paul II: while traveling to Tanzania, due to a technical failure, the papal plane had to make an emergency landing in Malta. Once again, the Polish pope saw the protective hand of the Virgin Mary in his life.

The popes of the 20th century have venerated Our Lady of Ta’ Pinu in a special way. Pius XI in 1935 sent one of his delegates, Cardinal Alessio Lepicier, to crown the image of the Virgin. John Paul II, in May 1990, was the first pope to visit this chapel, where he recollected himself in silent prayer before this image. After Mass, celebrated in front of the shrine, the painting was brought out and five golden stars were applied around the head of the Virgin Mary. Benedict XVI visited Malta in 2010. On that occasion, the image of the Virgin was brought from the shrine in Gozo to Malta. The pope gave a golden rose to the Virgin and urged the Maltese to pray to Our Lady Ta’ Pinu and called her “Queen of the Family.” Pope Francis visited the island in April 2022 and stood before the image of the Virgin at the national shrine of Ta’ Pinu.

Our Lady of the Cave and the Dominicans

It is said that around 1400 the Virgin appeared to a hunter, who had taken refuge in a rocky hollow because of a storm. Following this event, the devotion to Our Lady of the Grotto was born in what today is Rabat, then a suburb of Mdina. The faithful soon began visiting the cave and praying before the image of Our Lady. The first papal legate to confirm this new devotion among the Maltese was Frederick of Bordino, who in his will (1414) left oil for lamps to be lit before the image of the Virgin Mary. The tradition was always passed down orally until, in 1670, it was documented by the Dominican historian, Fr. Francesco Maria Azzopardo.

The origins of the church date back to the arrival of the Dominican friars in 1450. The order is very attached to Our Lady, and it’s a tradition to name Dominican churches after the Virgin Mary. One of the three friars sent to found the priory was a Maltese friar, Pietro Zurchi, who was surely familiar with the devotion to Our Lady of the Grotto. He was probably responsible for requesting this location for the foundation of the priory and the church, which stands above the cave of the apparition and is dedicated to Our Lady of the Grotto. The complex was completely restored in the 16th century because of severe damage suffered during the “Great Siege.” It’s said to be one of the most beautiful convents on the Maltese islands. Historian Gian Franġisk Abela wrote in 1647, “The crypt of Our Lady of the Cave has always been cared for with great devotion and love by our ancestors, so it is also done in our days and so it will be in the future.”

Almost nothing is known about the first image of Our Lady of the Cave. It’s possible that it was either painted on wood or painted directly on the wall of the crypt, a practice common at the time. The present image, in alabaster, is from the early 17th century. The Dominicans commissioned it to replace the original painting, damaged by moisture. In 1957, the Archbishop of Malta crowned the effigy of the Virgin Mary on behalf of Pope Pius XII. In 1980, the Dominicans commissioned a marble replica from Italy in order to save the original, which suffered heavy wear and tear especially during feasts and pilgrimages. On the occasion of the 1999 feast day, the replica remained on display for a few days in the church. A woman noticed reddish tears coming down from the Virgin’s eyes. Investigation and repeated analysis determined that it was human blood.

Throughout the centuries Our Lady of the Cave has not failed in granting graces. This is evidenced by the various ex-votos on display in the church. In particular, in 1887 a cholera epidemic struck the island: Many faithful invoked Our Lady of the Grotto and were cured. Twelve years later a smallpox epidemic struck Malta. Records tell that the parish priest from the town of Msida (the hardest hit) led his community to pray to Our Lady of the Cave. Msida was freed from the epidemic the very moment the vow was made.

Our Lady and the Bomb – The Rotunda of Mosta

The title of “Our Lady of the Assumption” is perhaps the most important one in the Maltese archipelago. All parishes existing until the early 17th century had at least one church or altar dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin Mary. In addition, three of the oldest parishes are dedicated to the Assumption: that of Birkirkara, which existed as early as 1402 (now St. Helen’s Basilica); the mother church within the Citadel of Gozo, mentioned in 1435; and the parish of Birmiftuħ, now called Gudja, which is mentioned in the Rollo de Mello of 1436. Today, nine churches in Malta and two in Gozo are dedicated to Our Lady of the Assumption, who holds a special patronage over the archipelago.

The Rotunda of Mosta is certainly the most famous church in Malta dedicated to Our Lady of the Assumption, both because of its special architecture, which makes it unique in the archipelago, and because of a miraculous episode. On April 9, 1942, during World War II, the German air force dropped four bombs on the church. One of them, weighing 500 kilograms (1,100 lbs), penetrated the church through the dome. All 300 people praying in the church were unharmed and the bomb did not explode. The dome also did not collapse, helping to confirm the exceptional nature of this structure. A few months later, on August 15, Assumption Day, a convoy, later dubbed “St. Mary’s convoy,” reached Malta’s Grand Harbor bringing crucial supplies. This not only averted Malta’s surrender, but enabled one of the greatest naval victories. The population attributed their liberation to the intercession of the Virgin Mary.

The Rotunda of Mosta, in its present form, was designed by the French-born Maltese architect George Grognet de Vassé, who was inspired by the Pantheon in Rome. The church was built between 1833 and 1860. It is perhaps the most monumental church in Malta. Its massive unsupported dome, with its 37-meter interior diameter, is the third largest in Europe and the ninth largest in the world. The church is a true work of art. In it, neoclassical lines inspired by the Pantheon are harmoniously integrated with elements of the Maltese culture. Externally, the building is made of local stone. Inside, it is decorated in neoclassical style and lit by large windows.

This content has been brought to you in partnership with the Malta Tourism Authority