“Lady, Our Lady,” writes Vittoria Colonna, “did you not press and pour/ into your milk, like essential oils wrung,/ the whole of you, like living breath into lung,/ to nourish the whole of your divine son?”

These words, taken from sonnet No. 51 of Colonna’s poems for Michelangelo (recomposed by Anna Key, this particular poem was published in the Poetry edition of the Word on Fire Journal), describe the Blessed Mother nursing the Christ child.

The image is startling — a mother gathering from within herself all that is necessary for life and serenely giving it away to her child.

The frightening power of maternal love

I’ve witnessed similar scenes of my wife nursing our babies. For 15 years now, she has regularly had some child or other wrapped close to her body, perhaps nursing while cooking dinner, embroidering, or sitting in the pew waiting for Mass to begin. I’ve seen her silhouetted by lamplight, nursing late at night, cheek quietly pressed to the milky white head of an infant, dozing while a tiny exploring hand massages and pinches her face. I’ve watched her collapse onto the bed at night only for a cry in the next room to instantly resurrect her against her will.

There is something almost frightening about it, the way that mothers casually give so much of themselves away. Heart and soul, as Colonna might say, poured out like wine from a press. It takes a visible toll. The difficulty on the body, the sleepless nights, the emotional intensity, it shines in the ragged happy eyes of new mothers. Other women struggle mightily with fertility issues or post-partum depression and its attendant feelings of helplessness.

No, I don’t think the image of a mother being squeezed under a wine press is particularly sentimental. It’s lyrical, yes, but as poetic metaphor it doesn’t flinch. It describes a reality that lies hidden just beneath the surface of everyday life – the beauty of a loving, maternal body stretched to the limit.

Life squeezes us all in particular ways unique to each person.

Giving ourselves away

In my vocations of father, priest, and writer I regularly find myself vulnerable and befuddled, almost confused at the acuteness of the way the universe pulls me apart and stitches me back together like some play toy, and yet I willingly volunteer, over and over again, to participate in the game.

My only desire is to give my life to something worthy of love. I’ve found that desire fulfilled in God, the Church, my wife, my family, and all the beauty that slips past my peripheral vision on a daily basis, the kind of beauty that vanishes when I turn to look and slips away from my ability to describe in words. There’s great struggle in our attempts to love, and pieces of ourselves fall away as we make ourselves a gift. It’s in those rifts that I glimpse Heaven. It’s the places where the sky weighs heaviest that my gaze pushes into the stars.

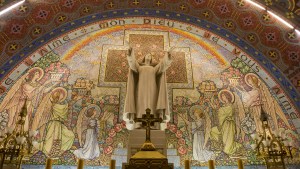

There’s something about motherhood, particularly the motherhood of Mary, that unveils both the hurt and glory of self-emptying. It’s a gesture that makes me unaccountably shy. Colonna feels the same, asking of Mary, “Did his living fire scorch your holy breast, and more,/ breaking into pure light and pure song/ the pieces of you like a universe born?”

A nursing mother, from the exterior, is a picture of familial bliss. But what of the self-sacrifice that creates the scene and, almost certainly, at least in little fits and starts, continues after it like a steady heartbeat?

The wine press of love

Novelist Katy Carl, telling the story of one of her deliveries, writes, “Here lay this perfect creature, now with his own life outside mine: velvety-skinned, cosmos-eyed, the very definition of vulnerability, infinitely precious, infinitely fragile. How could I carry us both forward into a world that could hurt so much?” And yet, there lies the baby in your arms, infinitely precious.

“Who can understand it,” Colonna wonders, “how spirit tore/ into the material world like lightning.”

The Solemnity of the Assumption is an event in which Christ calls his mother back into his arms, while perhaps not providing an answer in the sense that we can explain it in a catechetical sentence, does provide some understanding of the mystery. How it happens that a new life is created, a body endowed with and shaped by a soul, this we cannot know. How it is possible for the boundless God to fit himself into the material world and not burn it up in a flash. Well, this defies logic.

But in the Assumption the circle is closed, the self-emptying reveals how full it really is, the wine press of love, as Colonna says, is “Consoling like the evening’s red flush.”

Love does not venture forth unmet. We carry each other forward into the world. A mother her child. A husband his wife. A friend his friend. It isn’t without purpose, this sacrificial love we share, because it births something wondrous, so strong it could tear us to pieces but without which we cannot live.

****

Sonnet No. 51 by Vittoria Colonna

Lady, Our Lady, did you not press and pour

into your milk, like essential oils wrung,

the whole of you, like living breath into lung,

to nourish the whole of your divine son? Or

did his living fire scorch your holy breast, and more,

breaking into pure light and pure song

the pieces of you like a universe born?

Who can understand it, how spirit tore

into the material world like lightning,

did not burn but lit it up in a flash

that lasted through the long night, whitening

like snow the dark, dark world? In the flesh

he came and defied every logic, not frightening

but consoling like the evening’s red flush.