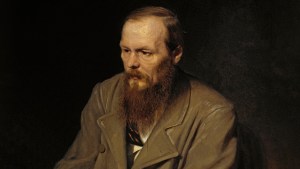

I first read Crime and Punishment when I was in college. I remember reading quotes like, “Pain and suffering are always inevitable for a large intelligence and a deep heart,” and thinking, Man, this Dostoevsky fella is wound really tight. I liked that, though. I was an insomniac melancholic young man. I was wound really tight, too. The darkness of Dostoevsky suited me just fine.

If you know his backstory, the writing starts to make more sense. When he was a child, Dostoevsky’s father was murdered by serfs — feudal workers bound to farm the family’s land. Then, as a young, aspiring author, he fell in with an anti-government intellectual group and was arrested. Their punishment was death by firing squad. The men were led out to a wall in the courtyard of the prison where soldiers with guns awaited them. A priest came and heard their final confessions. A wagon full of coffins was parked nearby. The order came for the firing squad to raise their weapons and Dostoevsky whispered to his friend that they were about to meet Christ.

Suddenly, a messenger on horseback arrived with their pardon. Instead of death, they were sentenced to four years in a prison in Siberia. A reprieve, to be sure, but Siberia was no picnic. He writes all about the ordeal in The House of the Dead.

A few years after release from prison and return from exile, Dostoevsky wrote Crime and Punishment. Perhaps this is why it’s so intense and the themes of psychological unraveling, violence, and subsequent guilt are so starkly portrayed.

It’s a book I’m glad I’ve read, but I’d be lying if I said it was a good book to relax with on the beach. I can’t claim I’m ready to read it again anytime soon. Sometimes great art, though, is difficult. It challenges us and leaves us better for having read it.

Crime and Punishment is great art for the subtlety of its psychological portrait of some very conflicted characters, but even more so for its hidden themes of redemption. The heart of the book isn’t doom and gloom. It’s all about redemption.

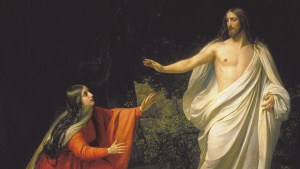

Dostoevsky was a devout Christian and his faith shines through in his writing. Two of the most recognizable Christian themes in Crime and Punishment are allusions to Lazarus and Mary Magdalene, both biblical characters who experienced extreme lows before finding redemption.

For instance, Raskolnikov is often described as dressed in burial rags and living in a sort of tomb because his evil deeds have deadened his soul. The reference is very clear if you manage to read all the way to the end. In the final two pages of the novel, Sonya reads the story of the raising of Lazarus to Raskolnikov. The story is even called a, “fulfilled prophecy.” Dostoevsky uses the parallel with Lazarus not only to illustrate how one man can, through God’s forgiveness and love, be redeemed, but he also means to say that his novel is an encouragement for every reader to rise up, come out of whatever spiritual tomb we may have fallen into, and find spiritual solace. There is no one who cannot be redeemed.

Mary Magdalene’s connection to the story

The feast of St. Mary Magdalene is coming up later this week, so I thought I might point out some of the allusions to her also. The character of Sonya resembles the popular characterization of Mary Magdalene (which is a mistaken version of this saint’s life) in many ways, most obviously in the fact that both women spend time as prostitutes. There are also more subtle comparisons. For instance, Sonya follows Raskolnikov all the way to the jail where he will turn himself in, just as Mary Magdelene follows behind Christ as he walks up to Golgotha. She selflessly and without word gives up her money to help others in the same way that Mary Magdalene pours oil on the feet of Christ.

In his Diary of a Writer, Dostoevsky says, “One can seriously believe in human brotherhood, in the universal reconciliation of nations, in a union founded on principles of universal service to humanity and regeneration of people through the true principles of Christ.” He truly believes that no one is beyond God’s ability to rescue and all the world is in divine hands.

This is the insight that I really needed back when I was reading Crime and Punishment as a young man. I was in an unsettled period of life, trying to figure out who I was and struggling to understand how God valued and loved me.

The fact that the story Dostoevsky tells is exceedingly dark makes the light of redemption in the end shine all the brighter. Lazarus is brought back from the dead. The “lost” Magdalene became a great saint. You and I, too, will be carried by God through whatever struggles we face, whatever mistakes we have made. There is always forgiveness and mercy. Always.

Crime and Punishment is long and at the very end, after many pages, Dostoevsky claims there is so much more to be written than we’ll ever know. In this, he alludes to John’s Gospel, again to the stories of Lazarus and Mary Magdalene. That Gospel ends with the same words, that there is more to life than can be written, more miracles than can fit in the world. God is still writing your story.