It is 1941 and the poet T.S. Eliot is suffering through the London Blitz. Like so many others, he lives out this particularly savage year of violent warfare in constant stress, not quite sure when the air-raid sirens will sound and German planes will appear in the skies ready to unload their deadly cargo. London has become a ruinous, dangerous urban landscape.

Eliot’s mind goes back to a more peaceful time and place, to his childhood in St. Louis, Missouri – to a house right around the corner from where I used to live – where he grew up along the banks of the Mississippi River. His family took regular vacations to Cape Ann, Massachusetts, which he remembers fondly.

Back in London, he had already been writing a poem about the river and ocean, full of memories, called, “Dry Salvages.” Years earlier, he’d completed a poem called, “Burnt Norton,” which is about an old ruined manor house in England. “East Coker” is another, about a Somerset village from which Eliot’s ancestors had emigrated to America.

These poems, in which he considers the ruin of war, nostalgia, loss, and regret in the context of redemption, eventually formed a completed poetry cycle called Four Quartets.

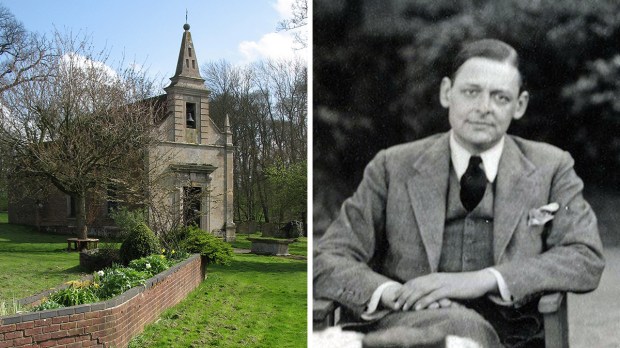

The fourth and final poem of the collection, “Little Gidding,” was published in late 1942. In it, Eliot recalls yet another experience. In 1936, he’d visited a strange little out-of-the-way community called Little Gidding in Cambridgeshire, England.

Although he only visited that one time, the memory of it clearly lingers with him as he completes the Four Quartets. He feels he needs to write about his time in that peaceful place to work out his emotions about all the death and destruction he has experienced during the war.

Little Gidding

Little Gidding is very old. The original buildings were built around 1196, essentially as a self-sufficient farming estate complete with a family chapel. The place had fallen into disrepair when a man named Nicholas Ferrar took possession around 1622 with money he made investing in the Virginia Colony. Nicholas was an ordained Deacon in the Anglican Church and envisioned living a semi-monastic life along with his family. Eventually, 40 family members lived in the community, where they would pray six times a day using the Book of Common Prayer and sit through long nights in the chapel waiting for sunrise. They observed fasting days and practiced works of charity.

The active religious community only lasted until 1657 when the last Ferrar brother died, but family descendants continued to live there for more than a century and the legacy of Nicholas Ferrar became ingrained with the place.

T.S. Eliot, visiting centuries later, still feels the prayerful presence, writing, “This is the nearest in place and time … here is the intersection of the timeless moment.” Clearly, the experience of that quiet place left a lasting mark on him, because this is where his mind returns when he begins questioning how it is that we journey through life, amid the horror of modern warfare, and how to reconcile ourselves to beauty when the world becomes so ugly.

The poem begins, “Midwinter spring is its own season/ Sempiternal though sodden towards sundown,/ Suspended in time …”

Midwinter spring

Springtime brings new life, but it’s a struggle. Flowers push up laboriously through sodden earth, terrible storms arrive on warm air currents, bursting with electricity. Spring brings sunny days and dawns when we wake up to frost in the fields. Over it all lingers the timeless God.

What does it mean, spiritually speaking, to find ourselves in a midwinter spring? There’s hesitation in the air, an uncertainty about whether the day will be a good one or will slip back into winter. These are days when we feel suspended in time. It’s a metaphor for how we become unsure of ourselves, unsure of how to deal with personal struggles, disappointment, violence, illness, or constant negativity in the news. Don’t fall back into winter.

Eliot seems content to wait right where he is in that middle place. The secret is that the timeless God gathers it all up, every experience of our past, present, and future, and keeps us close to His heart. The sun is stronger every day. The frosty fields at dawn glitter with divine pentecostal fire. We waver, “between melting and freezing,” but our journey is always proceeding The soul’s sap quivers with the beauty of the past, the hope of the future, and the goodness of the present moment, to be here, in our given place for better or worse.

Don’t give up. This is Eliot’s whole point. It doesn’t matter if you’re on an idyllic seaside vacation or suffering through the London Blitz. Our task is to keep moving even if it seems time is standing still.

“The end of all our exploring,” he writes, “Will be to arrive where we started/ And know the place for the first time.”