Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

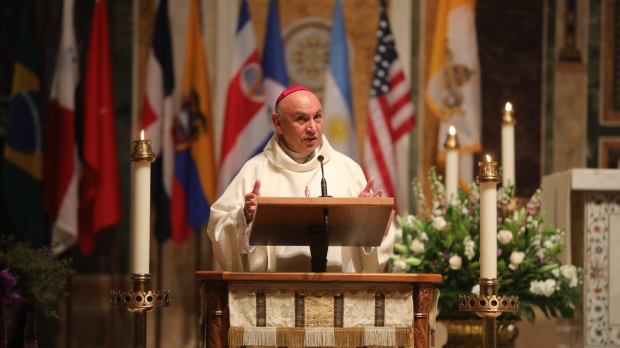

Hispanics are not the future. They’re already the present of American Catholicism. This is the belief of Bishop Mario Dorsonville, auxiliary bishop of Washington, D.C., and chairman of the USBCC’s Committee on Migration.

Bishop Dorsonville, Colombian by birth and incardinated in the U.S. since 1990, is very familiar with the challenges and difficulties of the Hispanic Catholic communities. He has witnessed the changes that U.S. Catholicism has undergone in recent decades. These transformations – at times quiet, at times discreet, but irreversible – have gone hand in hand with a growing Hispanic presence in ecclesial communities across the country.

This presence is not a novelty. On the contrary, it has been part of the American identity since the beginning of the country’s colonial history. This is a reality that must be faced with the spirit of integration that characterizes the universal Church, supporting the strengths they bring and fostering unity and belonging to the host country, explains the bishop.

The prelate granted an interview to Aleteia in the context of the upcoming Congress on Hispanic Ministry Raíces y Alas (“Roots and Wings”), to be held in Washington, D.C., April 24-30. The bishop will lead one of the central acts of the congress, which will consist of a formal petition to the senators on Capitol Hill for immigration reform and for a resolution in favor of granting citizenship to DACA immigrants.

Aleteia: You know very well what it’s like for a person from Latin America to integrate into American society. What would you say are the biggest challenges which need to be faced, and what concrete help is needed from the Church?

Bishop Dorsonville: The most important challenge is to make that cross-over to mutually understand the ways of feeling and thinking of Americans and Latinos.

Let me give you an example: in Latin America, in the mornings, people talk. Here, in the United States, people read the news. Anyone in the United States who talks at breakfast time is out of context, because what people need here is silence. It’s those little details.

The same thing happens with the liturgy. When you celebrate Mass for the English-speaking community, people arrive ten minutes before because everything is already organized. Everyone involved knows what they have to do, and how they’re going to do it. They’re simply waiting for the priest. When you celebrate the Eucharist in a Hispanic context, the experience is totally different. But that doesn’t mean that one is good and the other is bad. They’re different. And in the difference there are very good things.

The bishops wrote a letter 25 or 30 years ago called Strangers No Longer. In it they express appreciation for the fact that Latinos appeared in American society with some great qualities and clear principles: a deep love of family, an intimate relationship with God as a brother or as a member of the household; with a celebration of faith in a festive key that is experienced in their processions, in their songs, in all the human expressions found in the context of faith; and finally, a deep devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary. In fact, Our Lady of Guadalupe, as patroness of all America, has penetrated deeply in these last 30 years in white American culture. There are many churches that have images of Our Lady of Guadalupe. We have her here at the National Shrine. Africans, Asians, Hispanics, and Anglo-Saxons come to her… Mary helps us to evangelize and unite us as a universal Church.

I believe that one of the fundamental principles for those who come to the U.S. to serve in Hispanic ministry is a predisposition to understand the culture they’re coming to. It’s important to assimilate certain aspects and learn them in order to dialogue with that new culture. Immigrants also have to learn to accept other cultures, other ways of being and expressing themselves, and to see them not as a threat to their culture but as a cultural enrichment.

If there’s one very important thing that must be brought to the minds of the citizens of this nation, it’s that immigrants came to enrich the culture, not to destroy it. In addition, we have a common denominator which is that we are Christian. Immigrants do not bring a total change of values or religion, but a complement of different peoples and nationalities who believe in the same Jesus Christ.

A: You’re very familiar with the pastoral ministry with Hispanics in the United States. What do you think are the difficulties and opportunities in this area? Considering that there is a Hispanic aspect in the foundation of the country, is this need to show the American society that the immigrant is not the bearer of contrary values but of identical values and others that are complementary, a part of a difficulty or an opportunity?

MD: I believe that difficulties are always opportunities for human encounters that help us to dispel doubts. It’s true that the Hispanic people are inscribed in the very roots of this country, but there has also been an important flow of migrants in the last decades. And if the Catholic Church has grown in these last decades in the U.S. it is because of that, because of immigration. There is no other factor.

At this moment, there are almost 67 million of us Catholics in the United States. Of those, between 32 and 33 million are Hispanic. We’re already talking about almost half of the Church in the United States! Moreover, this Hispanic presence is no longer limited only to some southern states, but also in the center and near the Canadian border. There are now more than 5,000 parishes in the country with Hispanic ministry.

This brings us to understand that the future of the Church in the USA is also Hispanic. I say also because it is not only Hispanic. It’s a huge, multicultural conglomeration of Africans, Asians, African-Americans and Europeans. But, obviously, the largest minority is Hispanic. Unfortunately, we see that white Catholics are decreasing while the other cultural groups are growing.

This encounter which we are talking about as a challenge and an opportunity is happening in all the parishes where there’s a multicultural presence and, above all, a Hispanic presence. Here in Washington, 30 years ago there were only three or four parishes with Hispanic ministry. Today there are 43 parishes out of 137.

This poses an additional challenge: the shortage of bilingual U.S. clergy. Bringing a priest from another region isn’t the same as training him here in the United States. We bishops prefer to have clergy trained here rather than from abroad, for two main reasons. First, because these clergy are not permanent (at some point they’ll have to return to their dioceses of origin), and second, because there are difficulties with visas. We are at a very complicated moment in this aspect as well.

A: The Hispanic community in the United States is itself diverse. Indeed, the Hispanic community is not a homogeneous bloc. The national identities that make it up have different origins, different traditions, and different ways of living and celebrating faith. But when they converge and integrate in the United States, some traditions are lost and others are preserved. Would you say that in the U.S. a new “hispanidad,” a new concept of Hispanic Catholicism, is being born? Do you think we can already speak of a U.S. Hispanic Catholicism?

MD: I think we’re on the way but we haven’t achieved it yet. Devotions are very important because they represent a tradition that comes from grandparents and is carried in the heart. I always say that Venezuelans, Colombians, or Peruvians, when they come to the U.S., even if they keep their traditions, have to open themselves to the catholicity (that is, to the universality) of the Church, and to the society in which they live. They should remember with immense affection the land of their birth, but they must feel that they are citizens of this country.

I remember the first pro-immigrant march we had here at the Capitol. I told the attendees that we had to carry the American flag, because at the end of the day we are here. But they said “no, we are Mexicans, we are Ecuadorians.” In the end, there was a parade of flags here that looked like the Olympic Games. And this created enormous bewilderment in the American mind, because they interpreted it as if it was a set of foreign nations that wanted to raid American soil (and the American people). It’s very important, at this time, to put that aside. We have to bet on a new genesis. We have to continue grouping ourselves under the flag that unites us, and that the bishops have tried by all means to promote: the Our Lady of Guadalupe. There we find a message of unity that brings together Hispanic communities of different nationalities.

It seems to me, moreover, that it’s a mistake to assign priests of the same nationality as their parishioners. A parish priest should feel that he belongs to any of the nationalities he serves, in order to assimilate them within a pan-Hispanic context. This does not take away, at any time, the possibility of celebrating the procession of Our Lord of Miracles, or of Esquipulas, or of the Savior of the World. It’s fine for everyone to celebrate their own traditions. But this is a matter of one day a year, and not every day. The Hispanicity of the Catholic Church must continue to evolve so that we all feel as one family in one house.

A: This idea of “one house” refers to a fundamental biblical value: the hospitality of Abraham. You said in an address on Capitol Hill that welcoming refugees and immigrants was “more important than ever.” As head of the Committee for Immigrants and Refugees at the USCCB, you have spoken of compassion and solidarity. What do you think needs to change in society for that compassion and solidarity to be practiced? It’s evident that there’s a deep reluctance to welcome migrants not only in white communities, but even among Hispanic communities themselves. Serious episodes of xenophobia are also occurring in Latin American countries.

MD: This is a very important point. I’m convinced that, when we talk about change, we must first talk about a very important word: the opportunity for human encounter.

We often encounter false ideas about immigrants, fertilized by rhetoric that has no understanding of the truth. Human encounter often clears the barriers imposed by ignorance. I think that rejection is, above all, fear. Especially because when you don’t speak a language you feel excluded, and no one likes to feel excluded.

This is what Pope Francis has insisted on since the beginning of his pontificate: let us promote knowledge of the human person, encounter, so that human beings can dialogue, can know and understand each other, so we can build a much more fraternal and supportive society. Let us get to know each other in person, and not only through messages that can be false and manipulated.

I believe that the first step would be to make it possible for those under the DACA program to obtain their citizenship. This will do good to the minds of Americans, who may be skeptical about the presence of people who have entered their country illegally.

We see these generations of young “dreamers” who have grown up, who have studied, who have served, who have contributed to the economy, who are responsible sons and daughters. Some of them are fathers or mothers. Polls show that 70% of the American people believe, in fairness, that all those who are under the DACA program should have a clear path to American citizenship.

I believe that this is a fundamental step to consider, because many times it’s not words but encounters on an interpersonal level that really change ways of thinking. These encounters make it easier for migrants not to be perceived as a burden but as people who contribute to the development and future of the nation itself.

A: There seems to be a part of American Catholicism that is taking refuge in pre-conciliar devotional forms, and they see that as part of their Catholic identity, which is perfectly legitimate. But we also have communities that are bringing Hispanic ways of celebrating, of creating community, etc. In general, what can Hispanic Catholicism bring to U.S. Catholicism? Is there a new “American spirituality” forming as these two communities come closer together? Or on the contrary, are these communities not moving closer and is the American church culturally “ghettoized?”

MD: It’s a very complex situation. It’s hard to pinpoint where we’re really at, although there have been achievements. I remember the first Spanish Masses in Washington in the 1970s were held in basements, because the pastors didn’t want the heat or air conditioning to be expended on those “other” celebrations. It was quite complicated.

Unlike previous migratory waves, now there is not a total melting pot: Hispanics retain certain values which, thanks to technology, will never disappear. We have channels in Spanish, we have WhatsApp. They have permanent contact with their original cultures, which were never abandoned. The Irish left their country and never went back. In fact, they brought their whole family with them. This is not the case with Hispanic migration, much less with our Church.

The key is that we build a Church not in ghettos, but profoundly Catholic, literally universal. We can live the universality of the Church as long as we feel part of that universe. The great danger is in becoming a “national” Church, which is what happened before. This is the opportunity we see, from the episcopal point of view, to be totally loyal to the leadership of the holy Pontiff – be it Francis today, be it whoever it may be tomorrow.

The validity of the Second Vatican Council as a fundamental principle of the celebration of the liturgy in our Church, the inculturation of the Gospel as we accompany the grassroots Christian communities that exist in our diocese… these are all small seeds that are bearing fruit. They are not yet bushes, much less trees, but they are beginning to sprout. We have to give it time, but there has been progress. We’ve come out of the catacombs and are now in the churches. The National Shrine has a Sunday mass in Spanish. There’s also one at Christmas, and another one at Easter. The John Paul II International Center is bilingual. The Knights of Columbus, who were totally white, venerate Our Lady of Guadalupe and have her in their shrine. These are small steps but they show an openness to a universal church.

Now, one thing is very clear, which perhaps some do not see, and that is that the very future of the United States, no longer of the Catholic Church, but of the country itself, cannot be white. It’s going to be a culture that embraces many other cultures. It’s going to be brown. Not white anymore, but brown. This is clear, and in that sense there has been great progress. There are some dioceses in the south and southeast of the country that no longer ordain priests who do not have the ability to celebrate the sacraments in Spanish. It’s a requirement without which no mission is conceivable, because the churches are full of Hispanics.

Of course, we place all of this in God’s hands. He is the one who gives us the principles and the opportunities. In fact, the Hispanic Catholic’s way of thinking has changed and is evolving. It’s not that we’ve reached the end. We’re at the beginning, and there’s much to fix and manage. Some will not understand, and many times changing the mindset of a 60 or 70 year old is virtually impossible. But the new generations understand it perfectly.

Our evangelization also faces other challenges that depend not only on the multiculturalism in which we live, but also on all the disastrous attacks we face against the family, against life, against the dignity of the human person. Too many tendencies of this same society go against the very principles of morality and faith that we have learned from the Gospel. In reality, the only way to confront them is the unity and communion of the Catholic Church.

I would add, to round out all that we’ve discussed, that if there’s something beautiful about Hispanics, it’s that when we enter a new culture, we’re profoundly grateful. We must never forget that when we came to a foreign nation, there was always a hand that helped us, that understood us, and helped us to become better and better. This goes for all Hispanics and for all immigrants, because the worst thing that can happen in life to immigrants is for them to forget their own roots. When we forget who we are, it becomes easy to be unfair to newcomers. Sometimes an immigrant’s worst enemy is an immigrant with papers.

This interview was conducted by Aleteia staff writer Daniel Esparza and Inma Alvarez, Editor in Chief of Aleteia’s Spanish edition.