The biggest art exhibition opening in London this spring, featuring the Renaissance painter Raphael, is unusually full of religious content. Raphael is essential to the story of Catholic imagery. Where would Christmas-card publishers be without his two whimsical cherubs at the feet of the Sistine Madonna?

Not everyone loved Raphael so much in the 19th century. Perhaps because he had become the brightest star in the Renaissance heavens, a group of British artists showed their disapproval of the fawning admiration that surrounded him. In 1848 they formed the “Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.”

This band of brothers – and one part-time sister – wanted to turn back the clock to a less polished era. Above beauty and artifice they valued realism. They were not averse to Raphael’s love of religious themes, nor were they put off by the papal commissions that the 16th-century master relied on. It was not really Raphael himself they objected to; for these young rebels he cannot have seemed like an old fogey as he died at the age of 37. They just visualized things differently.

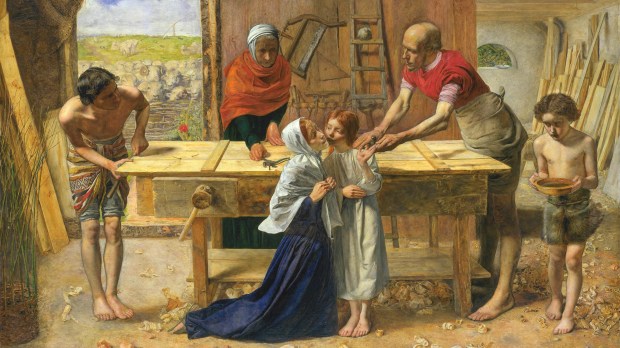

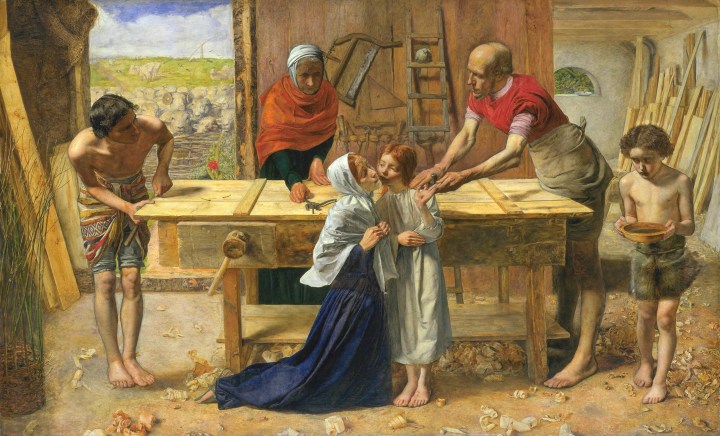

Perhaps the most brutally honest reworking of a sacred theme was Christ in the House of His Parents by J.E. Millais. Few paintings scandalized Victorian society as much as this one, shown at London’s Royal Academy in 1850. Where was the grandeur or good looks of the First Family of Christianity? The Pre-Raphaelite concern for realism had introduced, according to The Times: “misery, dirt and even disease.” Charles Dickens was alarmingly offended by the physical appearance of Jesus: “a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-haired boy in a nightshirt.” There was also “a kneeling woman, so horrible in her ugliness that she would stand out from the rest of the company in the vilest cabaret in France.”

Seldom has such scorn been poured onto a painting in which so much symbolism has been cleverly inserted. The most important element is the wound on Jesus’s hand as the blood drips onto his foot.

After this aberration, Millais went on to such success with the British establishment he eventually became a baronet (hereditary knighthood). Sir John Everett Millais Bart painted one strangely ecumenical scene, in which a Catholic girl tries to save the life of her determined but doomed French Calvinist boyfriend.

The Pre-Raphaelites were certainly not against Catholicism. Observers thought they leaned too far towards Popery and high-church Anglicanism. This was the time that the most-admired Church of England clerics were defecting to the Church of Rome. Millais even painted the super-star convert – the top Anglican theologian John Henry Newman who became the Catholic Cardinal Newman. In 2019 he was canonized by Pope Francis.

The Pre-Raphaelites liked to pursue matters of faith, especially if they could re-create a medieval look. Most enthusiastic of all was the William Holman Hunt, an evangelically inclined artist who travelled to the Holy Land to imbibe the Biblical backdrop. Millais, on the other hand, used a carpentry workshop in London as the model for his vision of the young, injured Jesus. Holman Hunt’s most famous work was one of the most-viewed paintings in the 19th century. His Light of the World marked a personal awakening to true belief and toured the world. Disturbing some of his huge audience were worryingly Popish aspects, such as Christ’s robes which were thought a bit too Catholic.

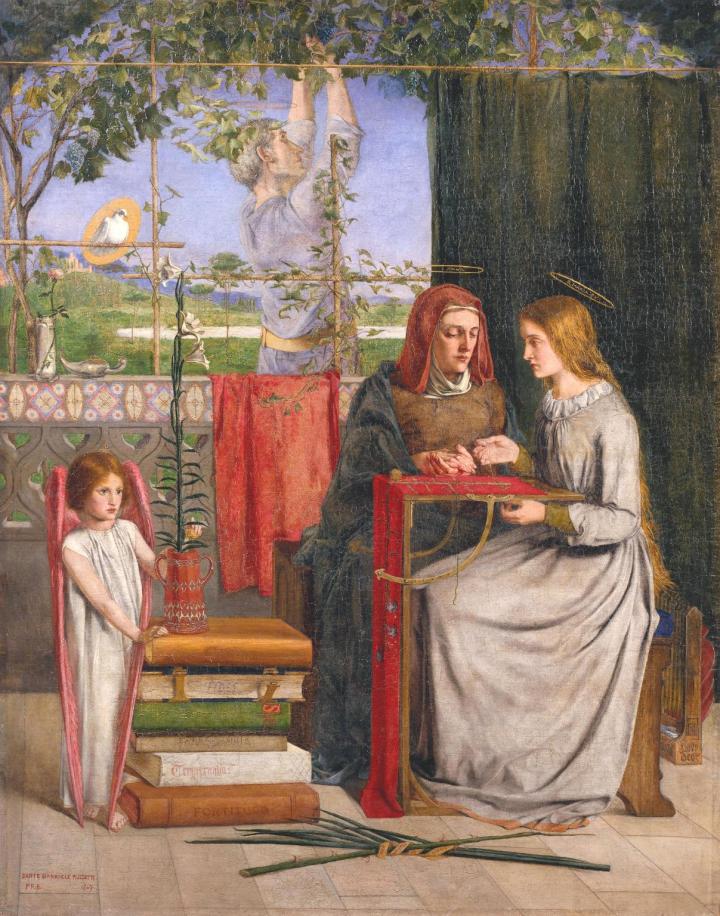

The actual religious beliefs of the Pre-Raphaelites are hard to classify and often wavered. None seems to have been a Catholic, although Dante Gabriel Rossetti was influenced by the Catholicism of his Italian father. Their faith was important to them, but so was experimenting with different subject matter.

Three hundred years earlier, Raphael hadn’t lived long enough to do much experimenting. Almost all his works are religious on the surface. He also appears to have been a devout Catholic despite having mistresses instead of a wife. The great Renaissance art writer Vasari believed that Raphael brought so much spirituality to his paintings, they caused miracles to happen. It can’t be said that the Pre-Raphaelites were responsible for any miracles, but some viewers at least had their faith restored.

In many ways, Raphael had a lot in common with the artists who chose to challenge his reputation with the name of their group. At least they didn’t call themselves the Anti-Raphaelite Brotherhood.