The concentration camps were a veritable killing machine. Millions of Jews, people with disabilities, those accused of acting against Germany, or individuals judged to not have enough Aryan blood, along with members of other groups the Nazis deigned undesirable, were executed en masse.

Catholics, mainly in Poland, suffered extermination and fought against it, sometimes risking their own lives to help others in the process. Many of those men and women have been raised to the altars for their dedication to others and their defense of the faith in those dark years of European history.

In August 2021, a new process of beatification began that has served to bring to light one of the many stories not only of heroism, but above all of hope in humanity.

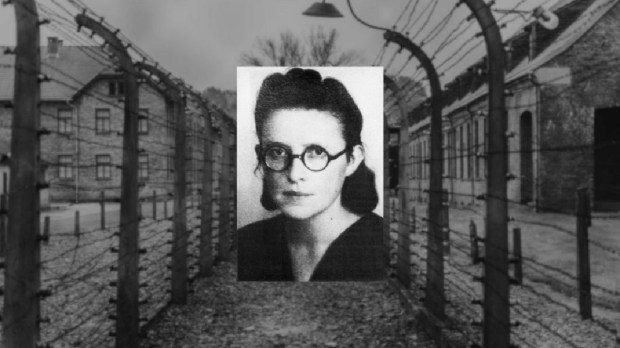

Stefania Łącka, like so many other people of her time, was not born to be a heroine. She was a simple woman, belonging to a Polish peasant family in which she, together with her parents and siblings, worked together as a team.

Born on January 6, 1914, from a very young age she experienced a deep faith. Every day she found a moment during the long days of work in the fields to take refuge in the church and pray.

At the parish, Stefania also took the opportunity to read, because the parish priest opened his doors to anyone who wanted to read in his extensive library.

Destination: Auschwitz

Eager to learn, the young girl put a lot of effort into her studies, which were cut short by the war. Before the German troops occupied Poland, however, Stefania Łącka had time to become active in various Catholic movements and to work as the editor of a religious magazine, Nasz Spraw.

After the Nazi invasion, the publication was forced to close, but continued to operate clandestinely. It was only a matter of time before she was arrested by the Gestapo on charges of collaborating with Germany’s enemies.

Transferred to a prison, Stefania Łącka was atrociously tortured, but the Germans failed to extract from her any of the names of her comrades who had not yet been arrested. Already then she began to show an iron will, not only enduring the abuse of her body but encouraging the rest of the prisoners not to let themselves be overcome by the irrational evil of their captors.

On April 27, 1942, she boarded a train that would take her to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. There she was no longer Stefania Łącka. She was, like the rest of the prisoners, a number: 6886.

Risking her life

Far from giving up, she refused to lose her humanity or to let the rest of the prisoners lose theirs. Her good knowledge of German enabled her to join the camp infirmary and gain access to some documents.

Stefania did not just give comfort to the dying. Even though she knew it would cost her life if she was discovered, she altered data to get some people off the lists of those condemned to the gas chambers or to receive a lethal injection. She also wrote letters to the families of prisoners, and shared the power of prayer with everyone she could.

When she was unable to save babies condemned to the gas chamber along with their mothers, Stefania Łącka didn’t hesitate to baptize them in secret.

Despite suffering a terrible outbreak of typhus and all the unimaginable hardships in the camp, the young Polish girl became a pillar of faith and hope. Stefania was determined to save as many people as she could, and, if she could not save them, to accompany them in their tragic fate by encouraging them through prayer. Her strength and courage would earn her the name of “guardian angel.”

“I will put myself in your place.”

Helenka Panek, another Auschwitz inmate, recounted years later that, standing in line waiting to hear the numbers of those to be executed that day, she was next to Stefania. Seeing Helenka nervous and distressed, she assured her that if her number came up, she, Stefania, would stand in her place to save her from death.

Stefania Łącka survived one of the deadliest concentration camps in history. When the war ended she was full of plans and began studying Polish philology at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow. However, her body had become so weakened after years of physical abuse and malnutrition that she died from tuberculosis on November 7, 1946.

In the church in Gręboszów, near where she was born, there’s a plaque in her memory in which she is remembered as a person “of deep faith. She brought a smile and hope, and many people owed their survival of the ordeal of the camp to her. Her kindness was providential in this hellish context of human suffering.”