Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

In 1866, an English priest named Herbert Vaughan opened a school named St. Joseph College of the Sacred Heart located in Mill Hill, England. He wanted to send missionaries into all parts of the world, and in 1870, he petitioned the pope for a mission field.

Meanwhile, the archbishop of Baltimore, Martin John Spalding, had been appealing to Rome for years for help in ministering to newly freed slaves in the US. In 1871, Pope Pius IX issued a document known as the “Negro Oath,” which Vaughan’s missionaries to America took to “vow and solemnly declare that I will make myself the father and servant of the Negroes.”

It was the birth of the Josephite Fathers and Brothers, who to this day are “committed to serving the African American community through the proclamation of the Gospel and our personal witness.”

Honoring the “first missionary”

With the “Negro Oath” in hand, Fr. Vaughan — later to become cardinal-archbishop of Westminster –and four other priests set off for Baltimore. Vaughan consecrated the mission to the Sacred Heart of Jesus and named his missionaries the “Josephites,” because St. Joseph was honored as the “first missionary.” The formal name of the Josephites is the St. Joseph’s Society of the Sacred Heart.

With the help of St. Katharine Drexel, who bought land for them, the small group established a seminary, parishes, schools and the beginnings of an interracial brotherhood. Missionaries would study at the college in England and then travel to America for their mission.

One of the original Josephites was an African American named Charles Uncles, a former parishioner of St. Francis Xavier in Baltimore. When Baltimore Cardinal James Gibbons ordained him in 1891 at the Baltimore Basilica, making him the first African American to become a priest in the United States, the event attracted national attention and coverage from The New York Times.

In 1893, however, Cardinal Gibbons offered to accept the Josephites as an independent organization, and the now-Cardinal Vaughan agreed. What began as a mission to help the newly freed slaves evolved into a society assisting all of the African American community.

Solicitude

The Josephites have made a “tremendous contribution to the evangelization and pastoral care of the African American community since … 1871,” Baltimore Archbishop William E. Lori said in 2013.

“Our commitment is expressed through sacramental, educational and pastoral ministry, service to those in need, and working for social justice,” the society says.

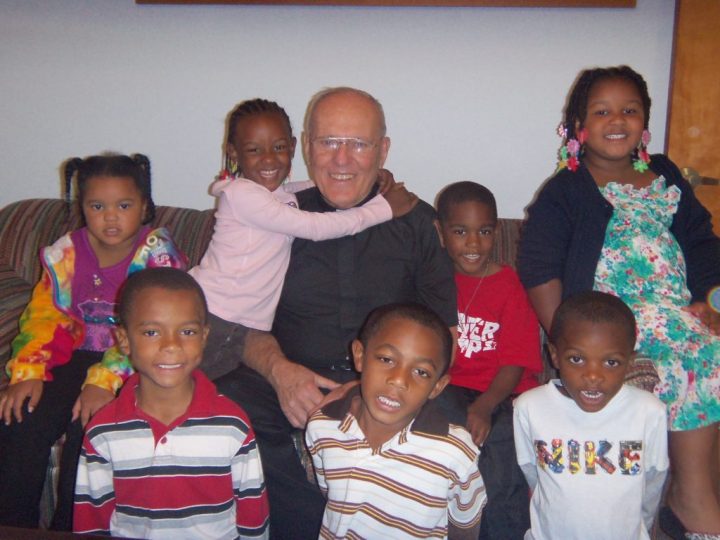

For Fr. David Begany, pastor of Holy Family parish in the Houston suburb of Baytown, that means “solicitude to the Black community, an awareness of how they experience life in America. Part of the Josephite charism is to recognize the needs of African Americans and try to promote their social welfare. I try to bring a sensitivity to what they’re going through. Our charism is to encourage them, be a spiritual father to them.”

Though other religious communities of men serve the Afican American community – the Society of the Divine Word and the Edmundites – the Josephites are the only community of men in the Catholic Church in the U.S. that is engaged exclusively in this particular ministry.

The Josephites have 38 parishes in Alabama, California, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Texas, Virginia, and Washington, D.C. They run four parish schools and St. Augustine High School in New Orleans, which is the only all-male, private African American Catholic high school in the U.S. A Josephite priest serves as chaplain at Xavier University in New Orleans, the only Catholic historically Black university in America. In addition, the society runs the Josephite Pastoral Center, an education, publishing, and research ministry in Washington, D.C., that specializes in resources for Black Catholics.

Archbishop Shelton Fabre of Louisville, Kentucky, is a product of Josephite education. He grew up in “and was formed in” St. Augustine in New Roads, Louisiana, a Josephite parish, and “is very proud of that background,” said Lonnie Thibodeaux, director of communications in the Diocese of Houma-Thibodaux, Louisiana, which Archbishop Shelton previously headed.

“African American Catholics are proud of their Catholic faith,” Fr. Begany told Aleteia. “The weekly attendance rate for predominantly African American parishes was about 40% (as of 2017), which is higher than the average Catholic parish.”

The priest said that Black Catholics have persevered in their faith, in spite of having been discriminated against in their own Church in the past – for example, having to sit in the back of the church or in the balcony, and having to receive Communion last.

“When I was growing up, even though I wasn’t Catholic then, if you visited a church that wasn’t Black, you had to sit in the back,” recalled Joycelyn Clementin, who became Catholic 50 years ago and is now a parishioner at Corpus Christi-Epiphany parish in New Orleans.

“Other parishes wanted to keep it separate but equal, but the Josephites were determined to break that down,” added fellow parishioner Albert Nicholas, 83.

Even the Josephites themselves, in the early days, had trouble getting Black candidates for the priesthood to the altar. “As the society matured, we accepted some Black priestly candidates, but often they were not accepted by the local episcopacy and thus could not be ordained or serve in dioceses,” said Fr. Begany, who is White. “Later, in the 1960s and 1970s, Black clergy were welcomed by the Church at large, and so some of them became Josephites.”

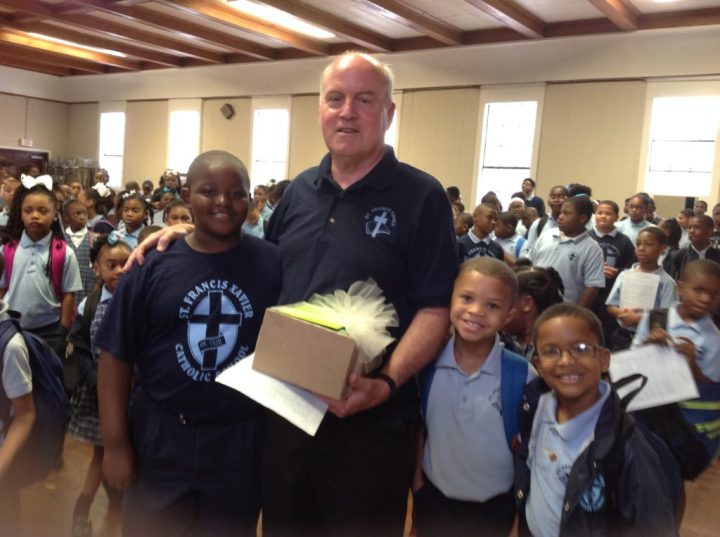

Forming the next generation

The Josephites also put their lives in danger as they served their people in parts of the South. In 1926, a Josephite priest, Fr. Vincent Warren, was briefly kidnapped by the Ku Klux Klan as he drove through Virginia to give missions to African American congregations.

The Josephites were instrumental in incorporating the African American cultural experience into the liturgy of the Church. And four Josephites and three laymen founded the Knights and Ladies of Peter Claver in 1909, the largest fraternal organization of African American Catholics.

Fr. Thomas Frank, pastor of Our Lady Star of the Sea in Houston, said the Josephites early on made the effort to start schools and collaborate with religious communities of women to teach in them, such as the Blessed Sacrament Sisters, the Oblate Sisters of Providence, the Holy Family Sisters, and the Holy Ghost Sisters. “At one time we had 19 parish high schools, so as a result we created an African American middle class of educated folks that we promoted not only in terms of Catholic education but also on to college and so forth,” Fr. Frank told Aleteia. And that got started before the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s.

Unfortunately, Catholic schools became more and more expensive to operate, he said, “and when you’re in marginal communities, where you don’t have the numbers or the income to sustain it, it became difficult to do.”

Fr. Frank added that the society was “very much part of the process to destroy segregation and to create integration rather than assimilation. Unfortunately, we’re still fighting that battle of integration versus assimilation.”

Many Josephite parishes are involved in Industrial Areas Foundation community organizations, Fr. Frank said. The IAF is a national community organizing network founded by Saul Alinsky in 1940.

“One of the things I found about IAF community organizations was that they’re interfaith and they’re interracial and consistent with the teachings of the Catholic Church,” said the priest. “They were nonpartisan. What they focused on were issues that were important to the self-interest of the community, and that could be anything from doing voter registration to saving school districts to having construction projects that various urban centers would get approved by their cities in bond programs, but then give those projects that were in the ‘poorer or working class’ areas so that they could benefit from them and not be put at the bottom of the list.”

On a prior assignment in Los Angeles, he was involved with One LA, and his parish was “deeply involved” in getting community colleges and businesses together “so they could get folks educated with jobs,” he said. “We also were dealing with the whole housing issue and the mortgages that went upside down because of those mortgage packages that were executed by some of the bigger banks.”

Going forward

As the society continues to minister to an African American community still facing many of its historical problems, the Josephites are seeking ways to address their own challenges. It has suffered from the same vocations dearth other communities have experienced in recent decades. From a height of almost 300 members, they’re down to 55 priests and three brothers, with 19 students in formation at the seminary. Part of the reason might be that it’s not really necessary anymore to join a particular community in order to serve African American Catholics. Diocesan priests can do so as well.

Over the past 15 years, the society has been recruiting in Africa, specifically Nigeria.

There’s also been a drop in the number of younger people in the Church, and some Josephite parishes tend to have older populations.

“Like everyone else, we’re trying to work out how we involve our young people and to sustain the parish community that provided the values and the education for these families to stay together and be in good shape economically and spiritually,” Fr. Frank said.

“Our mission of evangelization is just as important today as it was 100-plus years ago,” said Fr. Ray Bomberger, vicar general of the society (the Josephites’ superior general is Bishop John H. Ricard). “The challenges of incorporating the youth is a real challenge, and reaching out to the unchurched. And I think our social ministry in terms of seeking for justice in housing and healthcare and education, those of kinds of issues, our educational ministry [continue to be challenges]. Those schools were always a great source of evangelization and an opportunity to reach thousands, not only kids. … It’s a real challenge to reach out to them right now. How do we do that?”

Fr. Bomberger said that issues of racism “haven’t gone away” and in fact, “might even have become more insidious. It’s a continuing challenge to raise awareness. How do we address those things in today’s changing world?”

Fr. Begany added, “Some of the young seem to have a post-racial vision and say, ‘Oh, there’s no need to have a separate mission to Black Catholics. We’re all equal.’ And to them, that’s probably true. But in the greater society, unfortunately, that’s not the case yet.”

But judging from what the people they serve have said, the Josephites are a cherished part of the African American community. “They are beautiful, dedicated people,” said Joycelyn Clementin, at Corpus Christi-Epiphany in New Orleans. “I find they sacrifice a lot, they give a lot of themselves to the people. … The priests we’ve had here all went beyond the call of duty to be there for the parishioners.”

The only thing Kenneth DeGruy, the 77-year-old sacristan at Corpus Christi, doesn’t like about the Josephites is that “there are not enough of them around.”

Said fellow parishioner Albert Nicholas, “I wish they could canonize some of the Josephite priests I’ve met.”