How many nails were used in the Crucifixion of Christ? A look at how Jesus was depicted on the cross reveals much about the history of Christianity.

Venerating images of Christ’s Crucifixion is a custom shared by Catholics and Orthodox Christians. With the great schism separating the two for as long ago as a thousand years, there are also differences. Some of these relate to theology and authority. Others are more practical, such as the order in which believers “cross” themselves. Catholics go from left to right, while Orthodox Christians do the opposite.

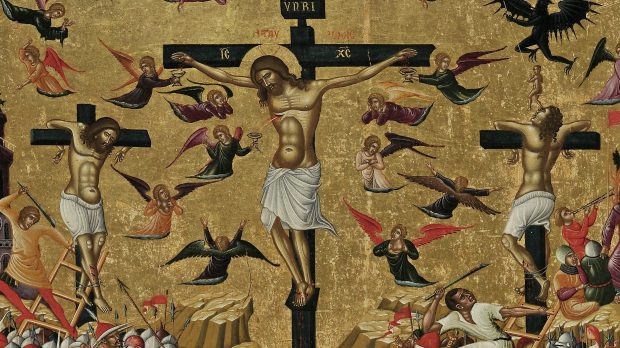

Within the Eastern Orthodox churches, it has always been four nails and a general lack of enthusiasm for crucifixes in “the round.” This was a result of Byzantine influence. The imperially endorsed Christianity of the Roman Empire was centered on Constantinople, the site of two periods of mass destruction of sacred images. Western Christians did not join in. They had to wait till the Protestant Reformation to witness similar devastation.

In Latin Rite Christianity, iconography was not set in stone – or wood or precious metal. Diverse images of Christ on the cross emerged in the centuries after the split with the Eastern Orthodox in 1054. The most widely accepted by Catholics today is the three-nail version that began to be seen since around 1200.

The timing of the switch from using four nails to three is hard to explain and easy to see. There were many discussions over the centuries concerning the nature of crucifixion. There is still little consensus on how the Romans performed the task. Being a shameful form of execution, there were few ancient writers prepared to describe the process. Archaeology doesn’t help much either. It appears that a variety of techniques were used in different places.

The evidence of Saint Francis

The stigmata of Saint Francis of Assisi were held up as proof that Jesus was crucified with four nails. It might seem strange that the presence of four wounds would be considered evidence, since three nails would cause the same number of holes through hands and feet. In the case of Saint Francis it was said that the outlines of four nails could be seen.

While disputes happened, artists went their own individualistic ways. With three nails and one leg twisted in front of the other, the creative possibilities of depicting pain were far greater. To show Christ as a suffering man was the objective. The Passion became something to truly ponder.

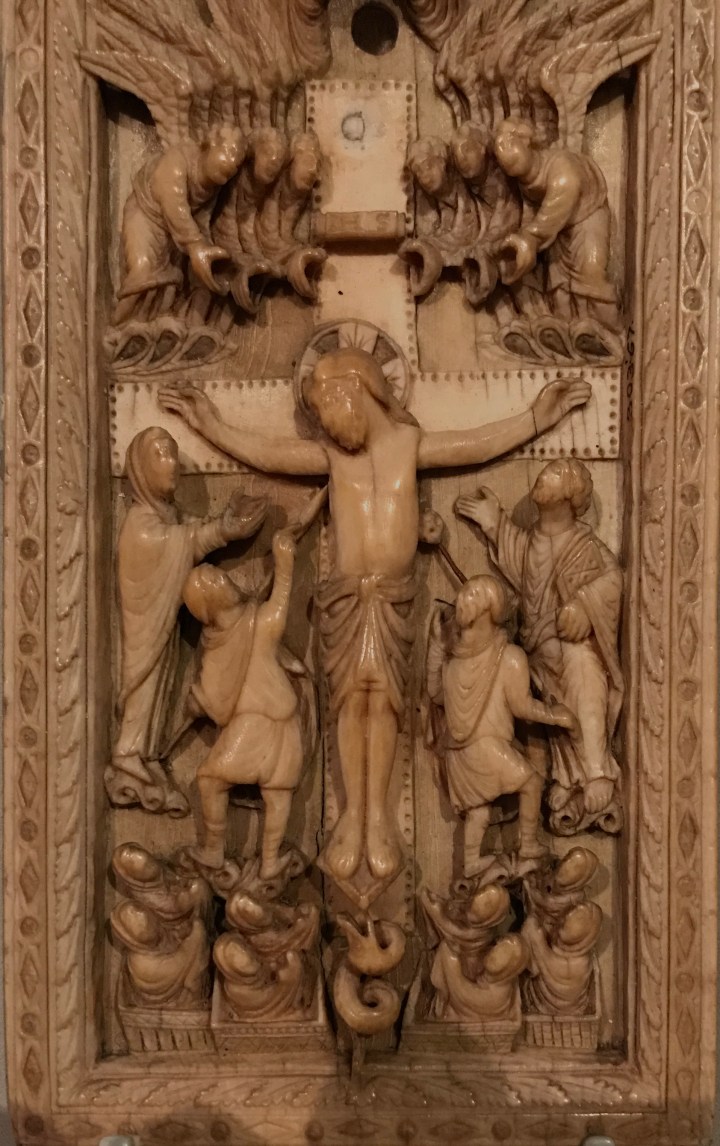

Everywhere that Catholicism travelled in its days of global expansion, missionaries brought the three-nail crucifix with them. In the Americas, Africa and Asia this became the basic form, to which local expressions might be added. The main exception in Africa was Ethiopia, where Orthodox Christianity prevailed. In Asia, some of the Corpus Christi figures that were exported from Goa and Sri Lanka to European royals did feature four nails. This wasn’t a theological divergence; the carvers were merely following the shape of an ivory tusk in the most economical way.

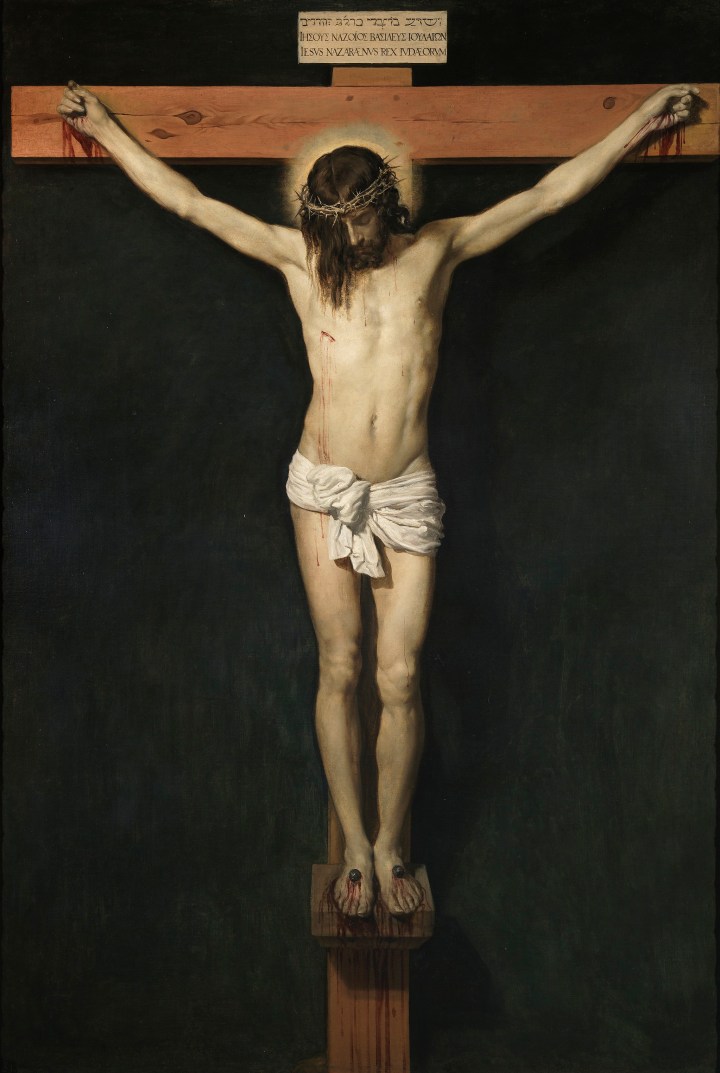

Many later European artists also took a different route. Masters such as Velazquez could build up massive emotional engagement with four nails and minimal contortion. By the 20th century the less-tortured Saviour had become common again, without the gore and pathos of the previous 800 years. A fully clothed Christ Triumphant on the cross is more about conquering death than the agony that Our Lord experienced beforehand.

Traditional visual values in the East

Meanwhile, Eastern Orthodox scenes of the Crucifixion continued in much the same way as they always had. When permitted, after the iconoclasms, they were required to be as two-dimensional as possible. The ancient shallow-relief, four-nail precedent has been maintained throughout Orthodox Christendom. One partial exception is Ukraine and its massive diaspora, much of which is in the USA.

The Ukrainian motherland is a topical and confusing place. Despite seeming very much the junior partner in its relationship with Russia, Kiev was the birthplace of Russian Orthodoxy. Christianity came late to that part of Europe. Only in 988 did a Kiev ruler convert his kingdom from its Slavic paganism. The land that is now known as Russia came next. Six hundred years later, the Moscow newcomers had taken control, which is how things have been until four years ago when the Orthodox Church of Ukraine received its credentials of independence for the top authority in Constantinople.

The uniqueness of this meeting place between “Eastern” and “Western” Christianity is occasionally confirmed by its depictions of the Crucifixion. The slanting footrest that makes most Orthodox crosses so distinctive is sometimes straight and parallel with the two other bars. Christ’s feet, which are always splayed apart in Russia, can be so close together on Ukrainian crosses it is hard to tell how many nails have been used. Ukrainian Catholics have been known to wear Ukrainian Orthodox crucifixes and vice-versa.

Further reconciliation is in the air. For some it will be too late; the Orthodox Church of Ukraine is now considering allowing Catholics to be buried in its cemeteries. Although this Church may have become independent of Moscow it is still sticking with most of the old ways, including the traditional four-nail crucifixes.

Turning to Turin

Perhaps the last word on the number of nails should go to the Turin Shroud. Scientific opinion is divided on many aspects of this important relic. One detail that seems to be conclusive is that it shows the wounds of a man crucified with three nails.