Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

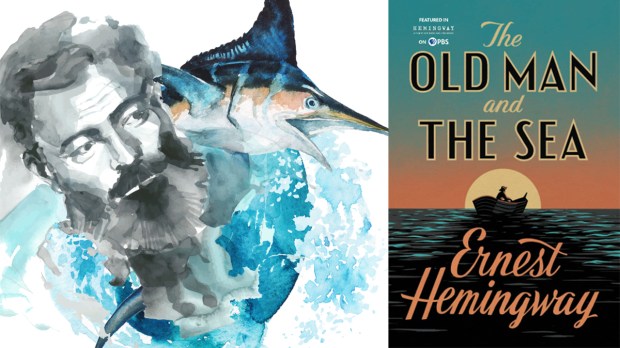

He was cursed or unlucky. Or, perhaps, he was just past his prime. Whatever the case, Ernest Hemingway opens his novel The Old Man and the Sea by telling us, “He was an old man who fished alone in a skiff in the Gulf Stream and he had gone eighty-four days now without taking a fish.” A widower, Santiago lived alone. He had moved his wife’s photograph off the wall (where it was framed near pictures of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and the Virgin of Cobre) because it made her absence too acute. “Everything about him was old but his eyes … which were cheerful and undefeated.” A young boy, whom the old man had taught to fish and had been in the skiff with him since he could walk, asked about the next day’s plan. “[I will] go far out to come in when the wind shifts. I want to be out before it is light.”

With the old man’s unfortunate hardship, the boy’s parents pointed him to a different boat — one that is less salao. “It was my papa made me leave. I am a boy and I must obey him.” The old man understood. “He hasn’t much faith,” the boy pawed the ground. “No,” Santiago said, “But we have. Haven’t we?” After talking about baseball, the boy looked at the old man and declared, “And the best fisherman is you … There are many good fishermen and some great ones. But there is only you.” The old man smiled, “I may not be as strong as I think. But I know many tricks and I have resolution.”

And so the old man would set out, alone, for the depths off the coast of his Cuban village. Many hours after he is at sea, his line is taken by something that proves to be tenacious and massive. In his attempts to wrangle with the fish, he recognizes that the size of the fish is something, in his many years, he has never yet encountered. It takes patience and nuance, he muses, to bring such a creature in. Every ounce of strength and every bit of wisdom is employed to outthink this enormous and beautiful creature. As hours and hours pass, the sun begins to set, and Santiago’s boat is being pulled into ever deeper waters. The line sears his hands, shoulders, and back as he waits for the beast to tire. At one point, the fish surfaces and leaps heavenward revealing itself to be a magnificent and impossibly large marlin.

As day turns to night turns to day again, Santiago is weakening. But he is still resolved. He catches smaller fish and eats them raw. He drinks sparingly of the water he has brought along. He talks to the beast and talks to himself. He waits for the fish to tire, to quit pulling his skiff into the deep, and to begin circling so that Santiago might slowly bring it in. When finally this occurs, it is the third day. With great difficulty, Santiago drags the massive marlin boatside where he harpoons and lashes it to the boat. It is time, now, to sail home.

But as the boat makes its long, uncertain journey home, Santiago fights exhaustion, thirst, and a touch of delirium. As blood from the majestic fish trails behind the boat, sharks descend upon it. Santiago is forced to stab and pummel the sharks, losing his tools as he does. But in spite of his tireless efforts, the old man finds himself overwhelmed by the relentless beasts. As his skiff arrives home, the hulking marlin is little more than an eviscerated skeleton.

Impossibly weary, the old man steps out of his boat, trudges home and collapses in bed. The boy, having worried that his friend was lost at sea, found him deeply sleeping in his home. When he inspected the old man’s torn hands, he wept. One fisherman measured the carcass still attached to the boat. “He was eighteen feet from nose to tail.” The boy, getting coffee from the village shop, heard the proprietor say, “What a fish it was. Never has there been such a fish.”

When my wife saw me reading The Old Man and the Sea, she grimaced. “Ugh. I didn’t like that book. I remember reading it in ninth grade and it just went on and on.” But I was blown away by it. An old man, washed up in the eyes of all but a faithful boy, carries on. Bereft of his wife, financial comfort, and professional success, Santiago puts out into the deep. His young eyes, which Hemingway describes as “the same color as the sea,” saw things differently. Hilaire Belloc described such eyes once in a shepherd he met in the high Downs over Findon Village: “[He] had in his eyes that reminiscence of horizons which makes the eyes of shepherds and of mountaineers different from the eyes of other men … He was perpetually in perception of the Unknown Country.” Through those same eyes, the old man saw vast waters and towering skyscapes, majestic marlins and menacing sharks with unbending faith and unshakable resolution. And when he towed the ravaged husk of his prize to the docks of his home harbors, he embodied the spirit of Teddy Roosevelt’s immortal words,

[The credit belongs to the man] who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.

Even in brokenness, the old man was more whole.

Upon awakening, the old man saw the boy keeping vigil beside him. Santiago confessed, “They beat me, Manolin. They truly beat me.” “He didn’t beat you,” the boy answered. “Not the fish.” The old man nodded. The boy looked at his teacher and friend, and insisted, “You must get well fast for there is much that I can learn and you can teach me everything. How much did you suffer?”

“Plenty,” the old man said, perhaps with a smile.

And then he drifted back to sleep.