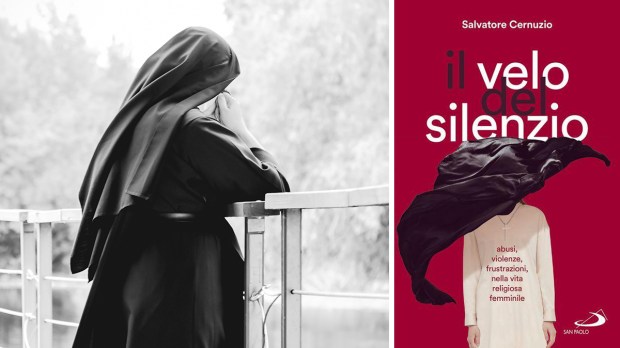

Spiritual abuse, sexual abuse, abuse of power or of conscience: These are dark realities in communities of consecrated women that Italian journalist Salvatore Cernuzio has sought to reveal. In The veil of silence. Abuses, violence, and frustrations in the religious life of women (Il velo del silenzio. Abusi, violenze, frustrazioni nella vita religiosa femminile, published in November 2021), this Vatican reporter gives 11 women a voice.

These 11 nuns, from all over the world and from different communities, were abused during their religious life. As a result, many of them have chosen to renounce community life. The journalist, who works for Vatican News, the official media channel of the Holy See, tells I.Media what he learned by lifting the “veil of silence” of abuse that sometimes covers the world of women’s consecrated life today. (Interview edited for length)

Why did you decide to write this book? What was your source of inspiration?

Cernuzio: My inspiration was an encounter with a friend who entered a cloistered monastery and then left. I found her after many years in a very different, almost dramatic state. Then there were articles. The first to sound the alarm were Donne, Chiesa, Mondo, [“Woman, Church, World,” the women’s monthly of the Osservatore Romano, Ed.] They published an interview with Cardinal João Braz de Aviz [Prefect of the Congregation for Institutes of Religious Life, Ed.] in which he spoke of the residence that Pope Francis wanted established to help former religious women. Later, in La Civiltà Cattolica, Fr. Giovanni Cucci’s investigation of the abuse of conscience and power in women’s communities was published. There, I asked myself how many women religious were now on the street and perhaps needed to speak out.

How is the book presented?

Cernuzio: The structure, which is almost a diary of each of these women, came naturally. I tried to be as objective as possible and I didn’t want to focus everything on sexual abuse. The message that this book wants to contribute, what these women are saying, is that there are abuses, besides sexual abuse, that are equally harmful to human dignity, such as psychological abuse, abuse of power, or abuse of conscience.

Each story in the book represents one of the macro-problems that afflict consecrated life: bullying, racism, sexual abuse, or illnesses that are ignored and go untreated.

How would you characterize spiritual abuse?

Cernuzio: Spiritual abuse is a symptom of a system that is sick. The root, in my opinion, is this syllogism that I have heard many times in these experiences: “You don’t want to obey, therefore you aren’t holy, therefore you don’t have a vocation.” This blocks a person’s spiritual and psychological maturation. These women were treated as minors, as if they had limited abilities, or perhaps as rebels, simply because they opposed or challenged an order; sometimes only because they had suggested the idea of studying or consulting the constitution of their religious order. The idea that one is always obliged to obey blindly can be a first step to abuse of power.

As I heard these stories, I was also struck by how these psychological and spiritual abuses or abuses of power played out in normal life situations. One woman shared that she had an objective health problem: depression. But the attitude of her sisters was that maybe it was her fault, maybe she hadn’t prayed enough, maybe she needed to step up her spiritual life or her work.

This is a subtle form of abuse designed to make the person feel even more guilty and victimized. Who do you turn to for help in this situation? One woman said to me, “There was no heaven for me”; I imagine they have all been in this situation.

In your opinion, do some of the situations described in your book reflect a more general problem regarding the Church’s attitude towards women?

Cernuzio: In my opinion, no, it’s quite the opposite. Some orders have remained as worlds apart. It’s true that the Church has a lot of work to do on the role of women—the pope himself has said so and has tried to act—but many orders or religious institutions have not moved on this point. They continue to hold on to anachronistic rules and traditions. I wouldn’t say it’s a problem of the Church, but of certain circles.

In fact, these women are not denouncing the Church as an institution. They are denouncing this situation, this wound, that they have experienced within the Church. These abuses are like small cancers that have crept into the body of the Church.

They felt isolated because they experienced an intrusion in their relationship with God, in their vocation.

Sr. Nathalie Becquart, in the preface of the book, speaks of an antidote to this evil: the synodal style. This journey, initiated by the pope, can be a great opportunity, like a blank slate that we hope will be used in the right way. Everyone can take advantage of this opportunity to make their voices heard and, eventually, to bring about change.

The Church, as Pope Francis says, must listen. The tragedy of sexual abuse has made us aware that we have often failed to listen to the victims and those who have suffered. The first step is to give credibility to what is said, from all sides, without taking anything for granted.

What instruments does the Church and/or the Vatican offer to support women religious who find themselves in these abusive situations?

Cernuzio: Those who have had the courage to go to the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life have received support and in some cases commissioners have also been sent. The dicastery carries out its own investigations and apostolic visits. But in my opinion, the problem lies somewhat earlier. The cases listed in the book are human problems that must first be resolved internally, within the orders and institutions themselves, before turning to the Vatican.

When a sister finally leaves her community, what support does she receive?

Cernuzio: The “ex-sister” is, let’s say, still a fairly unknown phenomenon, unlike perhaps the “ex-priest.” So, apart from the individual cases of people or communities who have taken care of certain women, or organizations like the Scalabrinian Missionaries project, I have not heard of other support, at least in Rome.

There is a lot of care and accompaniment in discernment when it comes to bringing people in, but there is not the same care when sisters leave.

The support also varies depending on the situation. For a young Italian girl who leaves a monastery or a convent, it is easier to return home to her family. She doesn’t experience the same drama as a foreign woman who is in Italy with a religious visa, not a residence visa, and doesn’t know how to change it.

Secondly, many women have entered these institutes at a very young age; they have no professional skills, and they don’t know how to work.

What can you tell us about the two houses run by the Scalabrinian Missionaries in Rome?

Cernuzio: The work that these missionaries do is valuable because they help women not only to heal their wounds but also to reintegrate into society. However, this project is vast, involving all women, lay and religious.

Perhaps we need a more specific service to these ex-religious women. But what is important is that these structures should not be considered as an easy way out [for the leadership of communities, Ed]. They must guarantee global support and accompaniment, on a spiritual, economic, psychological and professional level.