In the Soviet Union, religious practice was tolerated but certainly not encouraged. After an initial struggle against the Russian Orthodox Church, the regime allowed it to operate, but exerted measures to control it. It was generally considered unacceptable for members of certain professions, such as teachers, state bureaucrats, and soldiers, to be openly religious.

Fr. Alexander Men thought differently. The controversial Russian Orthodox priest reminded his followers what Christ taught: that Christians are to be the salt of the earth and a light for the world. He encouraged believers to not settle for the kinds of jobs the government allowed them to take, such as a security guard, but to strive to make their contributions, as Christians, in the world of art, learning and literature. He baptized hundreds of people, founded an Orthodox open university, and opened one of the first Sunday schools in Russia.

Born in Moscow to a Jewish family in 1935, Men was baptized at six months along with his mother in the banned Catacomb Church, a branch of the Russian Orthodox Church that refused to cooperate with the Soviet authorities. Ordained a priest in 1960, Men became a popular figure in Russia’s religious community in the 1970s. He was harassed by the KGB for his active missionary and evangelistic efforts.

On Sunday morning, September 9, 1990, he was murdered by an ax-wielding assailant outside his home in Semkhoz, Russia. He was on his way to celebrate Divine Liturgy. His murder was never solved. Fr. Men was 55.

Several years later, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Barbara J. Elliott met with Fr. Men’s widow and son and visited the priest’s final resting place. A former PBS reporter in Europe, Elliott was interviewing people in the former Soviet Union and Eastern bloc who had actively resisted communism because of their faith.

Fr. Men, Elliott said in a recent interview, “just spoke out for a free life in Christ and how that was incompatible with communism, which is built on an atheistic system. He was just fearless. He was also very charismatic and had a great following.”

The regime, Elliott said, tried to silence him, moving him to make it difficult for people to come hear him. But people would “get on the train to see him and just have a moving seminar on the way,” she said. “They just couldn’t silence him.”

Was he killed for his faith? “His wife knew that he was a martyr,” said Elliott, who now teaches at Houston Baptist University. “He knew what he was saying was dangerous.”

The Soviet Union, which for many in the West had been seen as the world’s biggest violator of religious freedom, finally disintegrated by the end of 1991. The red banner with its hammer-and-sickle emblem was lowered over the Kremlin for the last time on December 25 of that year.

Duty to remember

Time, it is said, heals all wounds. But time also can blur the lessons of history. Thirty years after the end of the USSR, when the West celebrated a victory over atheistic communism, some commentators worry that many people are forgetting how evil the “Evil Empire” was.

Even seven years ago, Žygimantas Pavilionis, then ambassador of the Republic of Lithuania to the United States, wrote, “Today we see the rehabilitation of Stalin’s reputation within the West as that of leader of an Allied Power that helped the West defeat Hitler, with little attention paid to Stalin’s atrocities committed before, during and after WWII. Within Russia itself, Stalin is increasingly viewed as a national hero, an opinion that has grown along with the size of Russia’s Communist Party in the Duma over the last decade.”

“Positive attitudes toward communism and socialism are at an all-time high in the United States,” says the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation. “We have a solemn obligation to expose the lies of Marxism for the naïve who say they are willing to give collectivism another chance. New generations need to confront the reality of Marxism in practice. Socialism is not a kind, humane philosophy. Marxist socialism is the deadliest ideology in history.”

The foundation’s website tells us, “Communism killed over 100 million.”

Indeed, that is a figure that far exceeds the number of people who died in the Holocaust, but most people are unaware of the extent of Stalin’s campaigns of genocide and political liquidations. The 2019 film Mr. Jones, about a Welsh journalist’s efforts to expose the Soviet dictator’s 1930s planned famine in Soviet Ukraine, the Holodomor, is one of the few on the subject.

The 100 million that the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation trumpets would include deaths in other communist countries, such as the People’s Republic of China, Vietnam, North Korea, and Cuba. But how many of those died in the USSR? Even before the fall of the Soviet Union, in the days of Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika and glasnost, a Soviet weekly newspaper published what the New York Times said was “the most detailed accounting of Stalin’s victims yet presented to a mass audience. The 1989 article indicated that about 20 million died in labor camps, forced collectivization, famine and executions.

“The estimates, by the historian Roy Medvedev, were printed in the weekly tabloid Argumenti i Fakti, which has a circulation of more than 20 million,” the Times reported.

Disputed numbers

In 1997, a number of European academics published The Black Book of Communism in French. That volume, whose English translation was brought out by Harvard in 1999, estimates the number of victims in the Soviet Union to be about 20 million. According to French historian Stéphane Courtois, who edited the book, the crimes by the Soviet Union included the following:

- The execution of tens of thousands of hostages and prisoners

- The murder of hundreds of thousands of rebellious workers and peasants from 1918 to 1922

- The Russian famine of 1921, which caused the death of 5 million people

- Decossackization, a policy of systematic repression against the Don Cossacks between 1917 and 1933

- The murder of tens of thousands in concentration camps in the period between 1918 and 1930

- The Great Purge, which killed almost 690,000 people

- The dekulakization, resulting in the deportation of 2 million so-called kulaks from 1930 to 1932

- The death of 4 million Ukrainians in the Holodomor and 2 million others during the famine of 1932 and 1933

- The deportations of Poles, Ukrainians, Moldovans, and people from the Baltic states from 1939 to 1941 and from 1944 to 1945

- The deportation of the Volga Germans in 1941

- The deportation of the Crimean Tatars in 1944

- Operation Lentil and deportation of the Ingush in 1944.

Yale historian Timothy Snyder, writing in 2011, challenged the figure of 20 million. After two decades of access to Eastern European archives, it was clear to him that the number of civilians killed by the Soviets was fewer than the number of noncombatants killed by Hitler’s National Socialists, which was about 11 million.

But, Snyder said, “Mass murder in the Soviet Union sometimes involved motivations, especially national and ethnic ones, that can be disconcertingly close to Nazi motivations.”

Snyder, author of Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, said the number of people who died in the Gulag between 1933 and 1945, when both those dictators were in power, “was on the order of a million, perhaps a bit more. The total figure for the entire Stalinist period is likely between 2 million and 3 million. The Great Terror and other shooting actions killed no more than a million people, probably a bit fewer. The largest human catastrophe of Stalinism was the famine of 1930–1933, in which more than five million people died.

“Of those who starved, the 3.3 million or so inhabitants of Soviet Ukraine who died in 1932 and 1933 were victims of a deliberate killing policy related to nationality,” he continued. “In early 1930, Stalin had announced his intention to ‘liquidate’ prosperous peasants (‘kulaks’) as a class so that the state could control agriculture and use capital extracted from the countryside to build industry. Tens of thousands of people were shot by Soviet state police and hundreds of thousands deported. Those who remained lost their land and often went hungry as the state requisitioned food for export. The first victims of starvation were the nomads of Soviet Kazakhstan, where about 1.3 million people died. The famine spread to Soviet Russia and peaked in Soviet Ukraine. Stalin requisitioned grain in Soviet Ukraine knowing that such a policy would kill millions. Blaming Ukrainians for the failure of his own policy, he ordered a series of measures — such as sealing the borders of that Soviet republic — that ensured mass death.”

Class warfare

Justifying mass murder on the basis of class, as Stalin said he would do in 1930 in the case of the Kulaks, should’t surprise anyone familiar with the history of Marxist-Leninism. As David Satter pointed out in a Wall Street Journal article marking the centenary of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, Vladimir Lenin said in 1920 that communists subordinate morality to the class struggle. Good was anything that destroyed “the old exploiting society” and helped to build a “new communist society,” Lenin said in a speech to the Komsomol — the All-Union Leninist Young Communist League.

“This approach separated guilt from responsibility,” wrote Satter, author of Age of Delirium: the Decline and Fall of the Soviet Union. “Martyn Latsis, an official of the Cheka, Lenin’s secret police, in a 1918 instruction to interrogators, wrote: ‘We are not waging war against individuals. We are exterminating the bourgeoisie as a class. . . . Do not look for evidence that the accused acted in word or deed against Soviet power. The first question should be to what class does he belong. . . . It is this that should determine his fate.’”

Satter agrees on the 20 million figure, which includes 200,000 killed during the Red Terror (1918-22); 11 million from famine and dekulakization; 700,000 executed during the Great Terror (1937-38); 400,000 executed between 1929 and 1953; 1.6 million killed during forced population transfers; and a minimum 2.7 million dead in the Gulag, labor colonies and special settlements.

“To this list should be added nearly a million Gulag prisoners released during World War II into Red Army penal battalions, where they faced almost certain death; the partisans and civilians killed in the postwar revolts against Soviet rule in Ukraine and the Baltics; and dying Gulag inmates freed so that their deaths would not count in official statistics,” Satter wrote. “If we add to this list the deaths caused by communist regimes that the Soviet Union created and supported — including those in Eastern Europe, China, Cuba, North Korea, Vietnam and Cambodia — the total number of victims is closer to 100 million. That makes communism the greatest catastrophe in human history.”

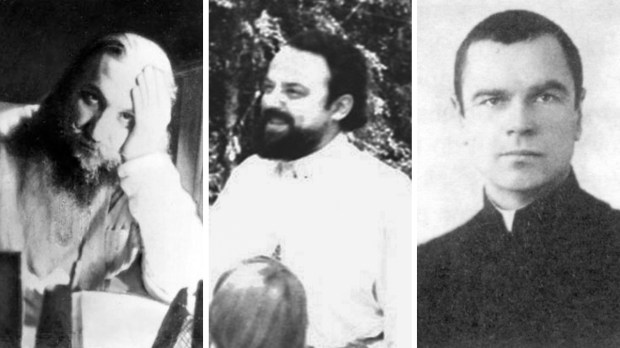

Three martyrs

To help put a face on some of those numbers, historians such as Robert Royal have done yeoman service. In The Catholic Martyrs of the Twentieth Century, Royal, founder and president of the Faith & Reason Institute, writes about Bartholomew Remov, a Russian Orthodox archbishop who became a Catholic in 1932. The Vatican made him the apostolic administrator of Moscow after Archbishop Eugene Neveu, returning to his native France for medical treatment, was unable to get back into Russia.

“Remov had already been arrested twice, in 1920 and 1923, simply because he was a prominent Orthodox leader, and then released, both times because of poor health,” Royal writes. “Through informers, the NKVD [the secret police and predecessor of the KGB] learned – or manufactured evidence – that Remov was giving Neveu information about the closing of Orthodox churches and religious persecution. He was arrested again in 1935 with 21 members of Catholic monastic orders. But his case was treated separately. Because of his eminence and importance, he was sentenced in a closed court session to ‘capital punishment by firing squad, with confiscation of goods.’ … The sentence was carried out in the Moscow Butyrka Prison.”

Volodymr Pryima was a Ukrainian Greek Catholic cantor. Born in 1906 in Western Ukraine, he attended a school for liturgical musicians and led the choir at his local village church in Stradch. He was married with two young children.

According to Catholic Online, on June 26, 1941, four days after the start of the German-Soviet War, Pryima accompanied his parish priest, Fr. Mykola Konrad, to visit a sick woman who had requested the Sacrament of Reconciliation. The two were detained by agents of the NKVD while returning through the forest to town. The agents tortured and murdered them. They were two of the 28 New Martyrs of Ukraine beatified by Pope John Paul II on his visit to the country in June 2001.

Fr. Janis Mendriks was born near Aglona, Latvia, in 1907. He entered the Congregation of the Marians of the Immaculate Conception in 1926 and was ordained a priest at St. Jakob’s Cathedral in Riga in 1938.

According to the University of Notre Dame’s book of Remembrance: Biographies of Catholic clergy and laity repressed in the Soviet Union, in 1942, Fr. Mendriks refused a Christian burial for a German police officer who was known to have been having an affair. The Nazis wanted to kill him and he was forced to go into hiding until the end of the war.

After the war, when the territory was occupied by Soviet forces, he once again took up his pastoral ministry. In 1950 he was arrested and sentenced to 10 years in the camps, which included work as a coal miner in Vorkuta in the Komi Republic. While in prison he secretly nourished the faithful, celebrated Mass and gave them the Blessed Sacrament, which he always secretly carried with him.

After Stalin’s death, the convicts, hoping for release, refused to go to work. When the authorities were not able to get them to submit, they decided to liquidate them. Fr. Mendriks remained with them in order to prepare them for their death, knowing that he would be killed along with them. He was in the first rows of those who were shot by soldiers on August 1, 1953. The Marian Fathers maintain that he died a martyr’s death.

He is one of 16 candidates included in the cause of “Catholic New Martyrs of Russia” opened in 2003.