Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

“Do you look for the Star of Bethlehem with the pope’s telescopes?”

Questions like this are all too familiar to those of us of the staff of the Vatican’s astronomical observatory. It is possible to undertake a serious study of the Star of Bethlehem—there was a significant conference on the Star in 2014 at the University of Groningen. But questions about the Star often are about what we human beings want to see in the sky, rather than about what anyone actually did see.

What do we know about the Star of Bethlehem?

The Star of Bethlehem is typically depicted as in the photograph below: an unmistakable sign in the sky; a big, brilliant celestial beacon, guiding the magi to the newborn Christ.

This idea is old. Aurelius Clemens Prudentius lived from 348 to 413. He wrote “Of the Father’s Love Begotten.” He also wrote “Bethlehem, of Noblest Cities.” It includes the following:

Fairer than the sun at morning

Was the star that told his birth;

To the lands their God announcing,

Seen in fleshly form on earth.

These words are a translation, of course. Prudentius actually wrote:

Haec stella, quae solis rotam

vincit decore ac lumine,

venisse terris nuntiat

cum carne terrestri Deum.

The Latin vincere is “to conquer.” Prudentius says the Star “conquers” even the sun—truly a mighty beacon! And so we like to imagine the Star blazing in the night sky:

They looked up and saw a star

Shining in the east beyond them far,

And to the earth it gave great light,

And so it continued both day and night.

But that mighty beacon is not the Star of Bethlehem described by Matthew’s Gospel. Matthew 2 tells us that the magi arrived in Jerusalem, asking about the newborn king. “We saw his star,” they said, “at its rising” (“in the east” is another translation). This news disturbed Herod, who “called the magi secretly and ascertained from them the time of the star’s appearance.”

Herod would not have had to ask when an obvious, bright object appeared in the sky. Everyone would know. It would be the talk of Jerusalem. Those “celestial beacon” images we all know, be they in ancient songs, in beautiful stained-glass windows, or even in tacky plastic illuminated crèche sets, are contrary to what Matthew tells us about the Star. They are about the star we want the magi to have seen in the sky.

Matthew tells us that the Star the magi actually saw was something that Herod and his scholars had completely missed. But it was also something that Herod could in fact see and comprehend. Otherwise, he would have dismissed the magi as crackpots—or, being the sort of person he was, had them killed for stirring up “fake news” about a new king.

Astronomers are very familiar with things in the sky that nobody else sees until we point those things out:

“Oh, there’s Saturn,” we say. “Saturn?” comes the reply, “How do you know that? It looks like just a star. I would have never even noticed it.”

“Look at the difference in color between Arcturus, Vega, and Antares,” we remark. “I never noticed that stars had colors,” we hear back.

What do astronomers tell us about the Star?

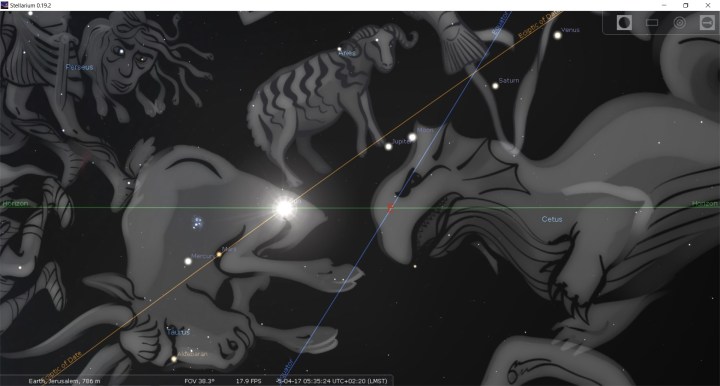

So, what was this Star of Bethlehem that only the magi noticed? The Groningen conference, held in response to work by a Rutgers University astronomer, Michael Molnar, discussed that. Molnar, looking carefully at the ideas of astrologers at the time of Christ’s birth, had argued that the Star was a certain arrangement of solar system objects in the sky that would have been significant to those astrologers (see image below). To a trained astrologer, that arrangement corresponded to a royal birth, in Judea. To the average person, it meant nothing. The Star would have passed unnoticed, unless pointed out by someone like one of the magi.

This simulation of the April 17 arrangement, seen from Jerusalem, was made by the author using the Stellarium planetarium app. The green horizontal line is the eastern horizon, the gold line is the path of the sun through the stars (marking the zodiac), and the blue line is the celestial equator. However, it is only certain details that make this arrangement portentous according to ancient thought. Nothing in that April 17 sky would have seemed unusual to the average person. Only Venus and Saturn would have been easily visible to casual observation. In fact, more eye-catching arrangements of the planets and moon have been visible in 2021, in the evening sky over the course of the past few months.

Interesting questions posed to the Vatican Observatory

The Vatican Observatory was not part of the Groningen Star of Bethlehem conference. The pope’s telescopes do ordinary astronomical research (although, as Vatican astronomer Fr. Paul Gabor, S.J. and I have recently discussed here at Aleteia, “ordinary” at the observatory can be “extraordinary”!). Nevertheless, we have had our own experience with the sort of celestial arrangement that Molnar describes.

In 2017 we received questions sort of like the one at the beginning of this article, but not about the Star of Bethlehem. Some folks wanted to know why the Vatican Observatory was not paying attention to a celestial arrangement that would happen on September 23 of that year. Various internet sources were telling how, on that date, the heavens would be arranged in a tableau of Revelation 12:

A great sign appeared in the sky, a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars.

On that day the sun would be in the zodiac constellation Virgo, the moon at the feet of Virgo, and the “nine” stars of the zodiac constellation Leo, plus three planets (Mercury, Venus, and Mars), would be at the head of Virgo—and thus the woman in Revelation 12. This was supposed to be a unique celestial occurrence that, like the Star of Bethlehem, would herald great events. Like Molnar’s version of the Star, it would not be noticed by most people. Indeed, it would be all but invisible.

In response to the questions, I wrote a post for the Sacred Space Astronomy/Catholic Astronomer blog at www.vaticanobservatory.org. In the post, called “Biblical Signs in the Sky? September 23, 2017,” I showed how, owing to the regular motions of solar system objects, this celestial arrangement was not unique. Similar ones had appeared in the September skies in the past. These had not obviously heralded great events.

“Biblical Signs” became Sacred Space Astronomy’s most-read post. It became the most-visited page on any Vatican Observatory web site—by an overwhelming margin. More than four years later, it still is often among the more visited pages at www.vaticanobservatory.org during a given week. We human beings love to read about great signs in the sky.

That love does not translate into love of learning about astronomy itself—about what we actually do see in the sky. Essentially none of the vast crowd of visitors who have come to read “Biblical Signs” has stuck around to follow the astronomical content on our web site. Alas, this remarkable fact suggests just how much more appealing is the idea of great signs compared to the reality of science, of ordinary astronomy.

That is unfortunate. Were we all more knowledgeable about ordinary astronomy—including the most ordinary astronomy regarding the how and why of the motions of the planets through the zodiac (which people can see with their own two eyes)—then we all might be less persuaded by hyped-up internet stories about signs in the sky.

But as it is, the idea of a mighty Star of Bethlehem pointing out the newborn king will surely remain popular, despite scholarly conferences and Matthew’s Gospel—and we will surely continue to get those “looking for the Star of Bethlehem” questions at the Vatican Observatory. I am sure the magi would understand.