It’s “keep Christ in Christmas” time again. You might have already seen the phrase this year, whether on social media, a bumper sticker, your local church, or elsewhere. True, the need to preserve and uphold the religious nature of this holiday is obviously mete and just. But saying “Xmas” instead of “Christmas” is not at all a scrubbing of the name of Christ out of the season. In fact, it is quite the contrary. The X in “Xmas” has literally meant Christ since the very inception of Christianity —or, as some like to abbreviate it, Xtianity.

Surely, some Christians (prominent ones included) make the “Xmas” abbreviation part of a larger (cultural) war waged against the popular “Happy Holidays” saying. And whereas the “happy holidays” greeting is just a way to make sure one is wishing everyone a joyful season according to their own religious affiliation (remember that, for example, Hanukkah and Christmas are more often than not celebrated a few days apart from each other), saying (or writing) “Merry Xmas” is not at all equivalent to tossing the name of Christ out of the season. It is actually a rather ancient tradition.

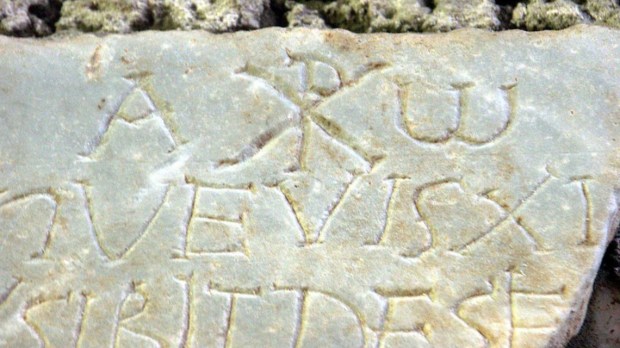

The letter “X” stands for Christ for a simple, straightforward reason. The word “Christ” in Greek, the language of the New Testament, begins with the Greek letter chi, “X,” reading “Xristós” (Χριστός). It was just a matter of time before theologians and scribes began to abbreviate the word “Christ” by just writing down either the first letter, X, or the first and second letters of the word, XP. These abbreviations are indeed quite common. Even the word God, theós, is oftentimes substituted by the Greek theta, θ, the first letter in the Greek θεός. These kind of abbreviations abound in Hellenistic texts from late antiquity, an the reason is also simple and practical: surfaces to write on were, in general, quite expensive back then, and any way to save as much space as possible while copying manuscripts was surely welcome. In fact, these abbreviations are rather ubiquitous, and come both in Greek and Latin. Saint Joseph, for example, was often referred to just as “PP” (hence the Spanish “Pepe”), for “Pater Putativus.” Even punctuation marks were quite scarce: we don’t find a list of these symbols until the seventh century, with the Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. Needless to say, paleographers often have a hard time deciphering some relatively uncommon abbreviations in ancient, late-antique, and medieval texts.

The XP abbreviation for the name of Christ, popularly known as the chi rho emblem after the Greek name of the two letters composing it (the X and the P being phonetically equivalent to our “ch” and “r” sounds) became especially popular as early as in the first half of the fourth century, when the Roman Emperor Constantine used it in his military banner in the famous battle of the Milvian Bridge. According to Eusebius, Constantine received a heavenly vision while praying.

[W]hile he was thus praying … a most marvelous sign appeared to him from heaven … when the day was already beginning to decline, he saw with his own eyes the trophy of a cross of light in the heavens, above the sun, and bearing the inscription, CONQUER BY THIS [In hoc signo vinces, “with this symbol you shall prevail”]. At this sight he himself was struck with amazement, and his whole army also, which followed him on this expedition, and witnessed the miracle.

Understandably, contemporary historians debate the authenticity of Eusebius’ account, arguing it is rather the stuff of legend, or that it was written in the typical hyperbolic language of late antiquity. In any case, what is certain is that by the fifth century the Chi-Rho was already being widely used in Christian art all throughout the Roman Empire, and that the XP abbreviation eventually dropped the P (rho). So feel free to wish your loved ones a merry Christmas, a merry XPistmas, or a merry Xmas, as tradition commands.

Make sure to visit the slideshow below to learn more about ancient Christian symbols.