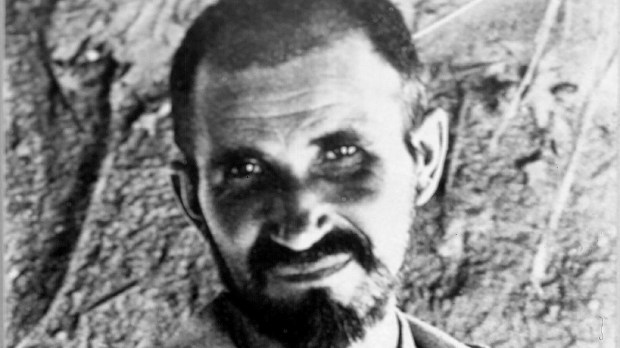

On May 15, 2022, Blessed Charles de Foucauld will be proclaimed a saint by Pope Francis in Rome. Bishop Jean-Claude Boulanger, bishop emeritus of Bayeux-Lisieux and author of “The Prayer of Abandonment – A Path of Confidence with Charles de Foucauld” (La prière d’abandon – Un chemin de confiance avec Charles de Foucauld) introduces us to this great saint.

“His whole life was a prayer of abandonment,” you write about Charles de Foucauld. Elsewhere you define the Blessed as a “guide for our time.” When we think of Paul VI’s statement that “contemporary man believes more in witnesses than in teachers, in experience than in doctrine, and in facts rather than in theories” (Evangelii Nuntiandi), in what way does Charles de Foucauld offer a model to be followed in today’s world? How can we follow this model?

Bishop Boulanger: Charles de Foucauld went through a period from his youth until he was 28 years old that shook him deeply, a mystical “night of faith.” He was a young man with no bearings after the death of his parents and his grandfather. He was in search of meaning, like many of our contemporaries and in particular the younger generations. He had more means to live than reasons to live—again, among the young, this is often the case. As such, he speaks a lot to the youth of today. He teaches us not to despair of God. He would even say: “God uses contrary winds to bring his boat into port.”

You call the prayer of abandonment of Charles de Foucauld, this act of offering, of trust and submission to divine action, his great teaching. How difficult is this attitude today for us modern people who like to have control over everything? In a situation that sometimes lends itself to despair, how can we pass, like Charles de Foucauld, from “Father, why have you abandoned me” to “Father, I abandon myself to you?”

Bishop Boulanger: At an uncertain time in his life, Charles de Foucauld meditated on the last words of Christ on the cross. He had given everything to Jesus, and his vocation suddenly seemed to be in question because the abbot had told him that he was not cut out to be a monk. This phrase of Jesus became the prayer of all his testimony. He didn’t know that this prayer would become the symbol and the image of what he was going to go through. He was going to abandon himself to God, to the priest as father, to Fr. Huvelin.

Very often, we’d like to be in direct contact with God. But Charles de Foucauld always trusted those whom the Church put on his path, even if sometimes he reacted brusquely: when Fr. Huvelin (his spiritual guide) told him that he was not made to lead others nor to found a congregation, Charles de Foucauld trusted him while expressing his astonishment. God uses human mediation if we trust the Church to lead us on the path of holiness. This path, as far as Foucauld was concerned, was long: he felt that God had abandoned him, especially when he no longer had any disciples. He considered himself like the olive forgotten on the tree after the harvest.

One does not immediately say, “Father, I abandon myself to you.” It’s a spiritual battle. We must take the path that Charles de Foucauld laid out for us.

You insist, with regard to the use of the term “Father” in the prayer of abandonment, on the disappearance of the figure of the father in our present cultural context, even its death. You also write that “sinful man rejects the fatherhood of God.” How do you conceive this “crisis of fatherhood” and of paternal authority in our present society? Why is the figure of the Father necessary for us today?

Bishop Boulanger: For several years now, I have been accompanying a charitable home in my parish and I have noticed that there is a profound crisis. The crisis we are experiencing is that fathers have become peers. They don’t accept fatherhood; they want to be friends with their children, similar to them. Sometimes they remain eternal adolescents. To become a father, one must accept to be dispossessed and die to one’s ego. What delights a father’s heart is to see his children grow up, become independent, assert themselves, and sometimes challenge him.

Charles de Foucauld, who was abandoned as a child (he lost his father and mother at the age of 5), received the grace, by contemplating Jesus, to contemplate him as Father: a father with a mother’s heart. “God is paternally maternal,” said St. Francis de Sales.

Many parents today exist only through their children; they expect everything from them. Their relationship is often fragile. They don’t accept it when their children take distance, when they build themselves up independently. Charles de Foucauld had the good fortune to meet a true father in Fr. Huvelin. When he died, he was able to say, “He was a father.”

You recall the death of Charles de Foucauld, who was found shot in the head on December 1, 1916, in Tamanrasset, a martyr of sorts by Islamic fanatics but a friend of Muslims. What does Charles de Foucauld teach us about these matters?

Bishop Boulanger: Charles de Foucauld always wanted to be a friend of Muslims, but also of unbelievers: soldiers, researchers, or Tuaregs. In this respect, he always made a distinction between Islam and the Muslims, to whom he owed a lot because it was they who, since his exploration of Morocco, had awakened in him this thirst for the absolute. He was not fooled by the political mixture of a certain Islam that sought domination. He understood how difficult it was for them to break with their way of life. We must remember that he was very close to the haratins, black slaves in the service of the Tuaregs, poor among the poor.

At the time of his death, in Tamanrasset, the looters intended to kidnap him. He was a valuable hostage at the time of the First World War to exchange for other arrested jihadists. The symbolism of that night is beautiful. When his body was found, the Gospel was found fallen on the sand: he had been meditating on the word of God. Next to it was found the Blessed Sacrament that he had been adoring, God made so small and silent. For him, evangelization in the Muslim world passed through the celebration of the Eucharist and the Blessed Sacrament. He did not speak of Eucharistic proximity but of presence. It is Jesus who gives himself to those among whom we live. Finally, he was writing a letter to his sister with the following sentence: “One can never love enough.”

The spirituality of Charles de Foucauld is based on three words: Gospel, Eucharist, and evangelization. He lived in a particular environment, in the midst of Muslims, where the word “God” is present in every sentence. Our environment is different, perhaps more difficult than the one in which he found himself: it’s an environment of secularization where the word “God” has disappeared. He wanted to give his life, despite the danger, like the grain of wheat that falls into the ground. He never doubted that one day the Muslims would recognize Jesus as the Son of God. He never turned away from the Muslims.

In what way is Charles de Foucauld also an enlightening figure for establishing a healthy secularism?

Bishop Boulanger: Charles de Foucauld understood that one should not impose a civilization or a religion on others. It happens not by force, but by “the apostolate of goodness, of closeness.” Our laws should not impose a way of life on believers. Charles de Foucauld suffered greatly due to the colonial presence of France, especially in Algeria, where our culture was imposed by force. The Tuareg chiefs were forced to learn French and to speak that language with the administrative officials. Charles de Foucauld spent 11 years writing a Tuareg-French dictionary and spoke the language of the Tuareg people in the hope that the Gospel could be translated into their language.

Imposing our vision today on our Muslim brothers is harmful. There will always be fundamentalists, but believing that the law can impose a way of life means touching the conscience of human beings. They should be invited to take these steps, but it cannot be imposed by coercion. Charles de Foucauld was hurt to see that the secularists of the end of the 19th century imposed the building of chapels and the destruction of mosques. He suffered to see how France at that time (anticlerical years) behaved culturally but also religiously.

Pope Francis concluded his encyclical Fratelli tutti (2020) with a mention of Charles de Foucauld. As a lover of Charles de Foucauld, did you find the spirit of the Blessed in the encyclical? Is the Pope an heir of Charles de Foucauld?

Bishop Boulanger: I have already spoken with him about this. He is very fond of St. Francis of Assisi, who said that in order to be a brother to the poor and the little ones, you have to accept to be one yourself. This is the path of Charles de Foucauld: the first of the Beatitudes concerns the poor in spirit. Like St. Francis, Charles de Foucauld needed time to accept his poverty and become small. Without being small, one cannot become a friend of the little ones. Pope Francis translates this expression well: only one who is small is capable of becoming a brother, he repeats, with Charles de Foucauld.

Interview by Augustin Talbourdel