Saintly living may seem too far, too cruel, too radical a means for living. “I believe in God,” we gently assure ourselves, even as we say, “but I’m not a religious zealot or anything.” Holiness is fine enough, as long as it’s tame.

A consuming fire

Yet the Christian God is not tame. C.S. Lewis makes this point, describing his Christ-like Aslan the lion, saying, “He’s wild, you know. Not a tame lion.” As the Scriptures say, “Our God is a consuming fire” (Heb 12:29).

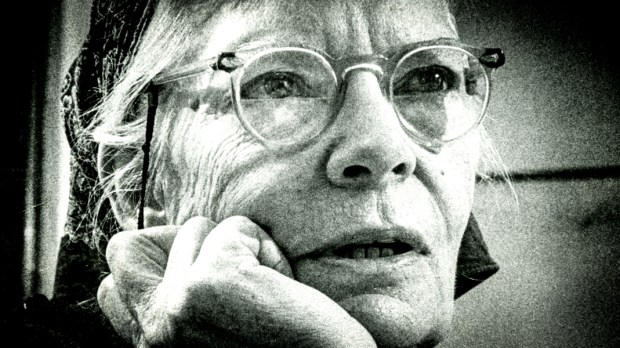

Dorothy Day encountered and framed her life in service to this mystery of God, the mystery of God’s love. She often quoted the description of love given in Brothers Karamazov by Dostyoevsky’s Father Zosima. The holy monk says, “Love in action is a harsh and dreadful thing when compared to love in dreams.”

Disillusioned

Dorothy’s extraordinary life took shape, no doubt, because of a disenchantment, a disappointment with the world as she experienced it. “I have been disillusioned,” she writes, “however, this long, long time in the means used by any but the saints to live in this world God has made for us.”

Dorothy famously converted to Catholicism after having written for several of New York’s socialist newspapers, including, The Call, The Masses, and the Liberator. The Masses was effectively shut-down when the postmaster refused to send it bulkrate (he considered the paper treasonous!).

Radical views

Dorothy held many radical views, including an extreme antiwar pacifism. More radical still was her devotion to the poor. Reflecting on a time when she was imprisoned, Dorothy wrote, “I would never be free again, never free when I knew that behind bars all over the world there were women and men, young girls and boys, suffering constraint, punishment, isolation, and hardship for crimes of which all of us were guilty.”

And even more radical than her love of the poor was her love of Christ. Describing her moment of conversion, Dorothy writes, “I wanted to be poor, chaste, and obedient. I wanted to die in order to live, to put off the old man and put on Christ. I loved, in other words, and like all women in love I wanted to be united to my love.”

Revolution

Once she became Catholic, Dorothy tossed aside her communist views on ownership. For her, belonging to the Church meant holding to everything the Church taught, without exception. She conceded, “I believe now with St. Thomas Aquinas that a certain amount of property is necessary for a man to lead a good life.” “I believe,” she continued, “that we should work to restore the communal aspects of Christianity as well as some measure of private property for all.”

Dorothy thought that the ills of society, the mistreatment of workers and the disparity of wealth, meant that revolution was all but certain. But she hopefully notes, “with the help of God and by resorting to his sacraments and accepting the leadership of Christ, I believe we can overcome revolution by a Christian revolution of our own, without the use of force.”

Dorothy’s revolution comes right out of the Gospel. Her revolution began in daily prayer (she was a daily communicant for decades and was deeply devoted to the Liturgy of the Hours). One member of the Catholic worker writes, “I began to realize how important my actions and prayers were to the health and well-being of the Church. For the first time I understood what Dorothy had meant, that cold morning, when she told me that by missing daily Mass I was hurting the work.”

And this revolution, born in prayers, takes flight in the works of mercy. Dorothy called the works of mercy her “indoctrination.” She explains, citing Scripture, saying, “We must give ‘reason for the faith that is in us.’”

Dorothy Day died November 29, 1980, after a lifelong revolution. The world is full of half-hearted loves and desultory causes. But as we remember Dorothy Day, let us remember first her saintliness, which she pursued with abandon. Hers was real holiness. The kind of holiness that causes a revolution of love.