As is often the case with other great Renaissance artistic giants, Michelangelo Merisi is better known by a single name, Caravaggio. The famous painter led a raucous and adventurous life and, wherever he went, he always managed to find himself in trouble. In numerous cities and places in Italy, from the Duchy of Milan down to the Eternal City and the Kingdom of Two Sicilies, and ending in the Southernmost Island State of Europe, the Hospitallers Principality of Malta, Caravaggio always found himself at odds with the law.

But his fiery character and well-known vices aside, he is one of Renaissance Italy’s greatest artists, and was also made a Knight of the Order of Saint John the Baptist of Jerusalem. One of his paintings is considered by almost all art critics and experts of the subject as the masterpiece parexellence of the 17th century: The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist.

Before we go any further, it is interesting to know the story of how and why Caravaggio found himself in Malta. We can understand the story better if we travel some years back before his arrival and see what happened in Rome during the month of May, 1606. Caravaggio entered into a brawl in one of the city’s notorious taverns. Another brawler, a certain Ranuccio Tomassoni, died in the fight. The painter was charged with Tomassoni’s murder, and he immediately fled from the Papal States. First, he went into hiding in the vast estates of the powerful Colonna Family, and then, to Naples. But Naples was too close to Rome for comfort and Caravaggio boarded a vessel and left for Malta. During his voyage to Malta, the talented artist thought about how to create a new school of painting, Southern Italian in character, reflecting the dark and melancholy spirit of an unfortunate region brightened by sharp and brilliant rays of light.

Living in Malta as a fugitive in his later years, Caravaggio created some of the most impressive and inspiring paintings of the 17th century, considered among the main representatives of the period in the history of European Art. His influence was such that he was the pioneer of a new school of painting — some call it Caravaggism — which spread rapidly in the Kingdom of Two Sicilies and Malta.

When Caravaggio landed in Malta, he still had the charge of murder hanging over his head. However, the Knights of Saint John did not lock him up in a dungeon. They had other plans for the young artist. The Grand Master ignored the Papal State’s demand for extradition of the suspected murderer and not only welcomed Caravaggio but granted him immunity if he agreed to paint for the State.The Order knew that one of the most brilliant talents was in their hands and they were not going to miss this golden opportunity. Here was a painter who was a sublime master in the use of dark and light, night and day, reflection and brightness. In one way or another, Caravaggio had to pay for the hospitality offered to him by the Order of Saint John. He had to adorn their Church with paintings reflecting his inimitable use of realism, and of humble chattels to depict holy religious subjects. Caravaggio was rather lucky because at that time Grand Master Alof de Wignacourt was also looking for a famous artist to paint his official portrait, and he could not have hoped for a better master.

Caravaggio grabbed the opportunity with both hands. Painting the Grand Master’s portrait would not only give him an occasion to redeem himself, but would also ingratiate him with the Knights of Saint John. According to Canon Law, if a person is created a Knight Hospitaller, ipsofacto, it meant that he had been graced by the pope. Caravaggio’s portrait of Wignacourt surely did not disappoint the Grand Master. It depicts the Prince in a proud pose, holding his scepter of command, standing straight as if embodying the military power, valor, and might of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem. Presently the painting is hanging on the walls of the Louvre in Paris.

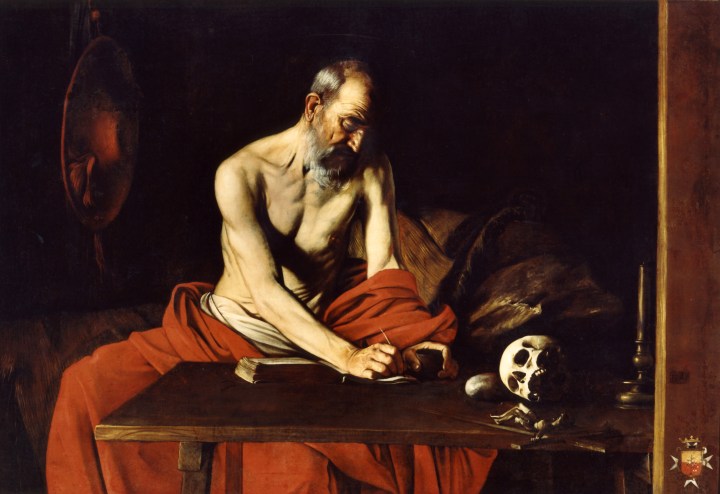

It was during Wignacourt’s reign that the Order began counterattacking Ottoman ports and raiding Turkish shipping. Caravaggio captured all this in the Grand Master’s triumphant gaze. The young page next to the royal figure of the Grand Master captures Caravaggio’s lust for life and his sensuous details reveal the great painter’s innermost character. Wignacourt’s famous portrait earned Caravaggio the Knighthood of the venerable Order of the Hospitallers. He was created a Knight in July, 1608. Documents relating to the investiture read: We wish to gratify the desire of the excellent painter, so that our Island, Malta, and our Order may at last glory in this adopted disciple and citizen. Besides the painting of Alof de Wignacourt, Caravaggio painted other famous works while in Malta, including Saint Jerome Writing and another painting called Sleeping Cupid.

But for the cultivated public, art critics, and all who are interested in the art of painting, Caravaggio’s masterpiece is The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist.It depicts the gory beheading of the Baptist as told in the Gospels. This is the largest painting Caravaggio ever produced, and the magnum opus of his entire career. Presently it hangs as the altar piece of the Oratory of Saint John’s Co-Cathedral. In his Caravaggio: An Artist through Images, Andrea Pomella describes this piece as “one of the most important works in Western painting.” In fact, it inaugurates a change of style in Caravaggio’s own trajectory. Most critics agree that this new style developed through his suffering and personal hardships. Even giants of the stature of Caravaggio grow by learning through suffering, as the Greek Dramatist Aeschylus remarked in his Agamemnon — Pathei Mathos.

In the painting, we find out that the Master focused not necessarily on the physical presence of the characters, but tried to offer a glimpse into their psychological depth. Rather than celebrating the bodily aspect of humanity (as in his previous works), Caravaggio here dwells on the kind of spiritual complexities at play in the sacrifice of the Baptist. Art critic Maurizio Calvesi notices how Caravaggio, through his characteristic use of light, captures the very last breath of Saint John. The macabre scene takes place in what looks like a dungeon; four people are on the left, the executioner, a prison guard, a young woman (maybe Salome herself) and a terrified old woman. Two other prisoners observe the execution from their cell. The empty space on the right is dramatically used to enclose the surrounding environment, as a frame. Indeed, the entire painting was created to become an integral part of its surroundings. The canvas is of the same dimensions of the wall where it was placed in the Oratory of Saint John. Also, Caravaggio thoroughlyobserved the behavior of the light in the chapel, to make the light on the painting an extension of the natural light coming in.

Malta Tourism Authority ©

In this painting, Caravaggio brings into play everything he has: a sharp rendition of the characters’ anatomy, a masterful use of chiaroscuro, a sober use of color, an insightful look into the depths of human pain. He intentionally used a restricted palette of earthy colors, with a single splash of bright crimson for the saint’s mantle. We notice also how skillfully he contrasted the freshness of youth with weary old age, the naked back of the executioner contrasting with the janitor’s rich green velvet robe. The painting is bathed with a beam of golden light, in an exceptional use of the chiaroscuro that later became associated with Baroque painting.

This painting is also unique because it is the only one of all Caravaggio’s works to be signed by the Master himself. One can spot the signature by focusing on the drops of blood dripping from the Baptist’s severed neck, which form the words Fra Michelangelo. The signature is evidence that Merisi had already been made Knight when the great painting was commissioned and completed.

But his sojourn in Malta did not have a happy ending. Again, his violent temper had the better of him. This time he embroiled himself in another brawl, where he physically attacked a neighbor of his, a certain Maltese Knight, Fra Giovanni Rodomonte Roero, an organist at Saint John’s Conventual Church. In Valletta, on the night of the August 18, 1608, Caravaggio was in Roero’s home and started a fight. The painter smashed Roero’s front door, and then seriously wounded the Knight-Organist. A day later, on August 19, Caravaggio was apprehended and imprisoned in Fort Saint Angelo. He was charged with attempted murder and for carrying a deadly weapon without a permit. On October 6 of the same year, he managed to escape from the fort. He immediately became Malta’s most wanted fugitive, but managed to slip away to Sicily.

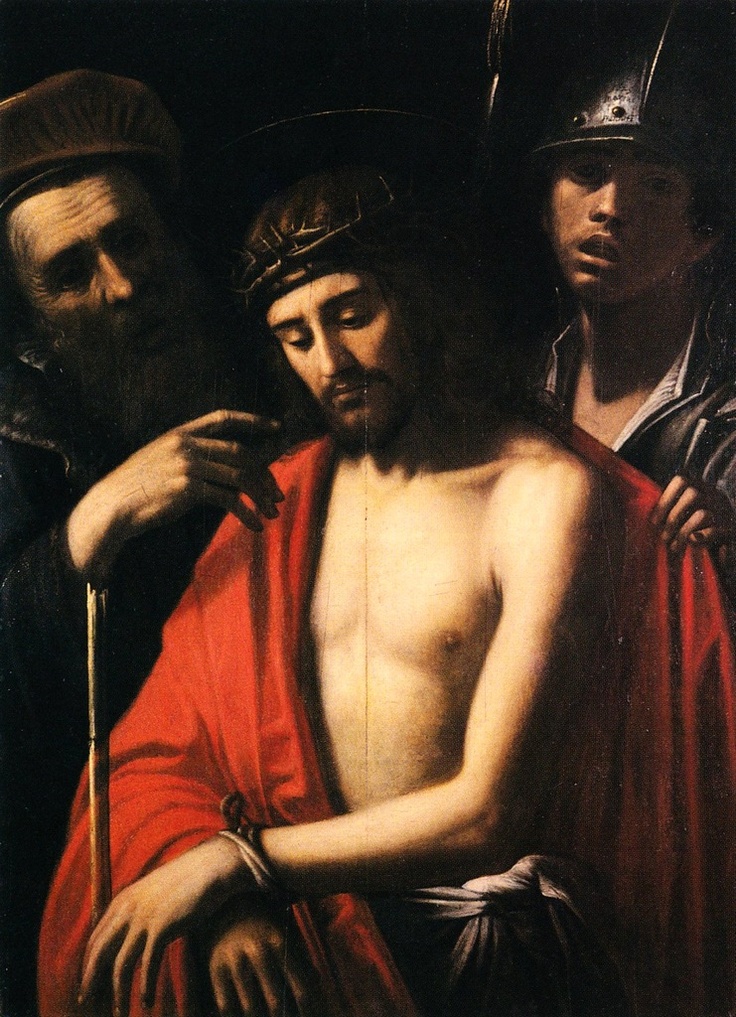

This painting is in the Baroque Hall of the

Mdina Metropolitan Cathedral Museum | Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The great artist died prematurely in 1610, without ever having set foot in Rome again. However, his style had struck deep roots in Eternal City’s artistic circles, and Roman Caravaggism became the mainstream style of his heritage. But in Naples, Sicily and Malta, his followers stuck to his Malta style. This school brought to harvest important and unique works of art. Despite the unhappy ending of his stay in Malta, the legacy Caravaggio left is as imposing as it is rich. And his legacy is not only enshrined by his masterpiece of the Beheading of Saint John, but also by the painting style displayed in his Maltese works, which influenced later generations of painters who created religious works during the following century.

Make sure to check the slideshow below to discover more of Caravaggio’s legacy, in the work of the Maltese Caravaggists.

References:

Caravaggio. Think Magazine. University of Malta. 10th September, 2012. Accessed 29th March 2021.

De Giorgio, Cynthia, ed. Caravaggio and Paintings of Realism in Malta. Malta: Midsea, 2007 (from Faith, Tradition and Glory).

This content has been brought to you in partnership with the Malta Tourism Authority