An exorcism is the practice of either casting out or getting rid of a demon. The Synoptic Gospels are full of demons and exorcisms alike.

Exorcisms in the Bible

Mark’s Gospel portrays Jesus as an inexhaustible exorcist, and Luke’s and Matthew’s (Cf. Mt 12:28-29; Lk 11:20-21) seem to suggest that particular, specific exorcisms prefigure Christ’s definitive defeat of evil, and of the consequent advent and realization of the Kingdom of God.

In fact, demons and exorcisms are so important in the Synoptic Gospels (exorcisms, interestingly, are nowhere to be found in John’s Gospel) that the Greek word “daimonia” is repeated 53 times. Two other similar expressions to refer to demons (pneuma ponera, Greek for “evil spirits,” and pneuma akatharta, “unclean spirits”) are also used with relative frequency —more than 10 times, at least.

Exorcisms in early Catholic history

Since the early Middle Ages, exorcisms and baptismal practices and rites have been closely related to each other. As early as in the 3rd century, there is evidence that, in the Western Latin Church, the exorcist was a minor order somehow associated with the subdiaconate, among porters, acolytes, and lectors. In the famous letter of Pope Cornelius to Fabius of Antioch (dated in the year 252, and preserved in Eusebius’ Church History), we read “he (Novatian) knew that there were in this Church (of Rome) 46 priests, 7 deacons, 7 subdeacons, 42 acolytes, and 52 exorcists, lectors, and porters.”

The Statuta Ecclesiæ Antiqua is a collection of 104 canons originally misattributed as being those of the Fourth Council of Carthage, held in the years 397-398. Nonetheless, they remain authentic summaries of early African councils. The seventh canon of the Statuta includes the rite of ordination of an exorcist that was in use until the early 20th century: the bishop gave the ordained the book containing the formulae of exorcism (either the ancient Book of Exorcisms or the Roman Missal) saying, “Receive, and commit to memory, and possess the power of imposing hands on energumens, whether baptized or catechumens.” These early canons also required that the exorcists imposed their hands on catechumens daily. Some similar practices are found in the Mystagogical Catechesis of Cyril of Jerusalem (4th century), in documents and codices belonging to the Apostolic Tradition, and in the Canons of Hippolytus of Rome (4th century).

More details on how these minor exorcisms, prayers, and ceremonies performed on adult catechumens can be found in Augustine’s works. In his On Marriage and Concupiscence, for example, Augustine explains that in Rome a form of exorcism practiced on catechumens included giving them a bit of exorcised salt, signing them with the cross, an imposition of hands, and two different symbolic respiratory practices. First, an exsufflatio (a Latin expression that could be somewhat translated as “out-breathing”) that symbolized the catechumen’s renunciation of the Devil. Considering that, as explained above, these spirits are referred to in the Gospels as pneuma akatharta or ponera, and that the Greek pneuma does not only mean spirit but also breath, this practice makes perfect sense. The exsufflatio would be followed by an insufflatio, meaning the in-breathing of the Holy Spirit.

The exorcisms of St. Guthlac

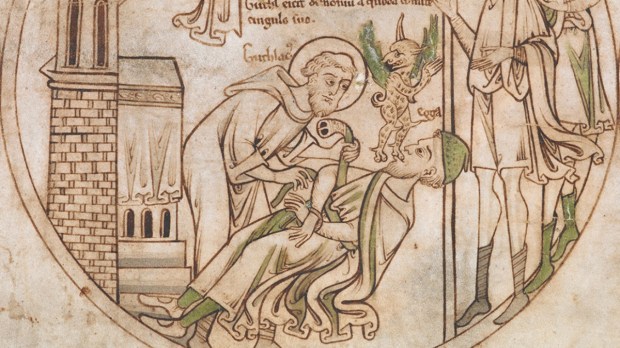

A very specific case of exsufflatio can be found in one of the many stories including demons and exorcisms associated with the life of the great St. Guthlac of Crowland.

Guthlac of Crowland was born around the year 673 (according to the Life of Guthlac written by a monk named Felix) in the English kingdom of Mercia, to a noble family related to the then-king Ethelred. He is one of the greatest hermit-saints of the early English Church (in fact, the most popular pre-Norman English saint, right alongside St. Cuthbert), and is also venerated in Orthodox Christianity, where he is often referred to as “the English St. Anthony the Great.” And just like St. Anthony, he was also tormented by demons over and over again. In Felix’s Life of Guthlac, we find several different passages describing Guthlac’s multiple encounters with these unclean spirits, who would dare to enter the saint’s cell:

They were ferocious in appearance, terrible in shape with great heads, long necks, thin faces, yellow complexions, filthy beards, shaggy ears, wild foreheads, fierce eyes, foul mouths, horses’ teeth, throats vomiting flames, twisted jaws, thick lips, strident voices, singed hair, fat cheeks, pigeons’ breasts, scabby thighs, knotty knees, crooked legs, swollen ankles, splay feet, spreading mouths, raucous cries. For they grew so terrible to hear with their mighty shriekings that they filled almost the whole intervening space between earth and heaven with their discordant bellowings.

The passage goes on to say that these demons took Guthlac and dipped him into the dirty waters of a nearby bog, threw him into a thicket of brambles, beat him with iron bars, and commanded him to go away from the island where he was then living as a hermit. But Guthlac paid no attention whatsoever to their threats, saying that he was not afraid of them at all. The Holy Apostle Bartholomew (Guthlac’s patron saint) appeared before him, giving him a scourge (or whip), and the demons immediately disappeared. Hence, Guthlac is always represented as holding a whip in his right hand, with a demon lying at his feet.

The exsufflatio story, however, does not involve Guthrac’s whip, but his belt. The story goes that a man named Ecga was possessed by an unclean spirit. He was, literally, an energumen — the Greek energoumenos meaning “being under the influence of.” Some of his friends brought him to Guthlac, since he was utterly unable to understand what was happening to him. Guthlac took off his belt, wrapped it around Ecga’s waist and squeezed it until the demon was “breathed out” (“exsufflated”) through Ecga’s mouth.