The remains of St. James the Greater, one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus and patron saint of Spain, may not actually be resting under the main altar of the great Cathedral of Compostela.

The cathedral itself was built over the site where tradition tells us the remains of St. James (or Santiago) were discovered, and the pilgrimage to Galicia, Spain, known as the Camino de Santiago de Compostela celebrates the miraculous events that led to the discovery of the Apostle’s remains.

A recently published study suggests his remains might be the ones kept in the legendary Chapel of the Relics, located in the very same cathedral, where those of the other James, “the Lesser,” were thought to be kept.

The forensic anthropological study was carried out in the 1990s, but was just recently included in the most recent edition of the prestigious journal Forensic Anthropology, published by the University of Florida.

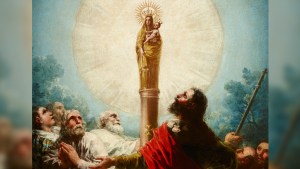

According to ancient Iberian tradition, on the second day of January of the year 40, the Virgin Mary appeared to James by the river Ebro at Caesaraugusta (today’s Zaragoza) while he was preaching the Gospel in Spain. After the event, James returned to Judea, where he was beheaded by King Herod Agrippa I in the year 44. During his mission years in Spain, he made seven main disciples (the noted Seven Apostolic Men), who were then ordained in Rome by Sts. Peter and Paul and sent back to Spain to complete James’ mission.

These traditions were later compiled, in the 12th century, in the Historia Compostelana, an anonymous chronicle written during the tenure of Diego Gemírez, the first archbishop of Compostela. The chronicle includes a thorough summary of the story of St. James as it was believed and told in Compostela at that time. It clearly states James preached the gospel not only in the Holy Land but also (and mainly) Spain and that, after his martyrdom, his disciples carried his body by sea to Iberia (Spain). They landed on the northern coast of Galicia, and took the body inland, finally burying him in Compostela.

The last time the relics kept in the Cathedral were scientifically studied was back in 1878. At that time three professors from the University of Santiago (Professors Casares, Freire, and Sánchez Freire) claimed that the bones found buried under the main altar belonged to three incomplete, different skeletons. The finding confirmed what tradition always claimed: namely, that James the Son of Zebedee (that is, James “the Greater”) had been buried in Spain with two of his companions.

In his archaeological investigation, Casares also found the remains of an ancient Roman mausoleum underneath the cathedral. This mausoleum is believed to be one of the possible origins of the name “Compostela,” the Latin word for cemetery being compositum. In fact, this ancient Roman cemetery has been part of the Compostelan tradition since the 9th century, when pilgrimages to the site began. Even more importantly, the name of one of James’ disciples was found engraved on one of the stones found in the mausoleum. The scholars concluded that the bones found could reasonably have belonged to the Holy Apostle and two of his companions.

Tradition claims James’ disciples brought the body back to Spain from Jerusalem, after his beheading by order of Herod Agrippa I around the year 44, and buried him in this compositum. But it took some 800 years and a miraculous shower of stars to discover the exact place: a hermit named Pelayo said that he had seen a shower of stars (or some brightness in the sky, or at ground level, according to other versions) in the forest of Libredón. This would be yet another explanation for the name Compostela: campus stellae, “the field of stars,” in Latin. He informed Bishop Teodomiro, who in turn sent a communication to King Alfonso II of Asturias and Galicia. The king ordered the construction of a chapel in the place, which would immediately become an important center of pilgrimage.

Here’s where things get confusing. The remains of another St. James were introduced to the story in 1108, when, according to medieval historical documents, Portuguese Bishop Mauricio Burdino brought the head of James, son of Alphaeus (the apostle the Gospels refer to as the “brother” of Jesus, James “The Lesser” or “The Younger”) back to Iberia with him. Enter Queen Urraca.

Urraca was certainly an exceptional (and fearsome, formidable) woman. She was, no less, the first reigning queen in European history. She ruled over Castilla, León, and Galicia, and claimed the titles of both Empress of All Spain and Empress of All Galicia. But, perhaps more importantly, during her marriage to Raymond of Burgundy, she introduced herself as the “ruler of the Land of St. James.” She managed to seize the relic from the Portuguese Burdino and hand it over to the then-Archbishop of Compostela, Diego Gelmírez, who deposited it in a golden chest. The year was 1116, seven years into her reign.

It might have been the case that Urraca tried to gain even more political leverage by claiming she had finally brought home the missing remains of James The Elder, even if that contradicted the already two-centuries long established tradition initiated by King Alfonso II in the year 813. After all, we know from the Book of Acts (Cf Acts 12, 1-2) that James was beheaded, so bringing home his head might have made some sense — as if she had reunited it with the remains the disciples were able to bring, assuming the head was still missing. It is also possible that some confusion arose upon the arrival of the relic, and that people (who were naturally already more familiar with the Son of Zebedee than with the Son of Alphaeus) simply assumed the head belonged to James the Greater. After all, The Greater had been beheaded, while James The Lesser was bludgeoned to death instead.

Whereas some traditions claim The Lesser died crucified in Egypt, the widely accepted version explains he remained in Jerusalem for over 30 years. His ministry there was eventually met with harsh opposition from other religious factions in the city, and around the year 62 he was hurled down from the top of the Temple to an angry mob below. Having survived the fall, he was then stoned and bludgeoned to death with clubs. In scientific forensic jargon, he died from a traumatic brain injury. This suggests his skull could not have been the virtually intact one that Burdino brought with him from the Holy Land.

A century after the studies led by Casares, Freire, and Sánchez Freire, the Cathedral decided it was time to determine not the identity of the remains of the Son of Zebedee but those of the Son of Alphaeus instead. For many different reasons, it took the team led by Fernando Serrulla some 30 years to conclude the new study. And its findings, although not conclusive, are not necessarily entirely clarifying either. In short, it might be the case that the head that was believed to be that of the Son of Alphaeus (the one brought by Burdino) is in fact that of the Son of Zebedee, which would have been misplaced for centuries inside the very same cathedral.

The very different deaths of the two Jameses played a key role in Serrulla’s attempt to solve this relic riddle. The few preserved remains that could be analyzed do confirm a violent death, but not necessarily one consistent with what we know about the martyrdom of Alphaeus. Serrulla’s forensic reconstruction determined the victim suffered two main wounds: one in the frontal part of the skull, and the another one in the parietal. The study then explains that these two blows to the skull might suggest this execution was a case of the so-called “death by three blows.“

The infamous “death by three blows” (a common Roman form of capital punishment) involved the convicted person receiving the first strike on either the frontal part or the side of the head with a heavy weapon — oftentimes a sword, yet not using its sharp edge. This first blow would just make the victim unconscious. The second one, aimed at the back of the neck once the body was on the ground, was intended to kill the person. And finally, the beheading — just to make sure the prisoner was in fact dead.

The remains found in Compostela can only confirm the victim received the first two blows, since not a single vertebra has been preserved: the third strike can only be inferred from the previous two, clearly visible in the skull. The skull does not show any wounds that can be attributed to the kind of death suffered by The Lesser. The remains are consistent, instead, with a beheading. Serrulla concludes that the skeletal remains found in the reliquary of James, Son of Alphaeus, may not belong to this saint. On the contrary, they could belong to James, Son of Zebedee, instead.