When most people think about St. Francis, they picture an enraptured beggar gently petting a wolf while holding a white dove in his other hand. But the real St. Francis was a much more complex figure.

The Fioretti di San Francesco (Italian for “Little Flowers of Saint Francis,” an early collection of popular legends regarding the life of the saint and his early companions, most likely written by Franciscan chronicler Ugolino Brunforte) did a lot to propagate today’s image of St. Francis.

What might surprise some people is that, in short, he went from being a medieval noisemaking partygoer somewhat obsessed with King Arthur to renouncing his inherited wealth and embracing a life of radical poverty —all of this while, yes, experiencing mystical ecstasies.

Here are four little-known facts about the popular Italian saint.

His name was not Francis, but John.

Born in either 1181 or 1182 (the exact date of his birth is rather uncertain), he was baptized at his mother’s request as Giovanni di Pietro Di Bernardone, after St. John the Baptist (Giovanni Battista, in Italian). He was later renamed Francesco (Francis) by his father, Pietro Di Bernardone —a rich cloth merchant who made his fortune trading with France. The new name of the child was an enthusiastic homage to the country that had brought him wealth —Francesco loosely translating to Frenchman.

He was a party-going wannabe-warrior.

Hagiography, popular tradition, and some biographers tend to describe the pre-conversion Francis as a kind of quasi-libertine party animal. This is only partially true. He had surely been spoiled by his parents, and was respected and perhaps even enviously admired by his fellow citizens because of his wealth and amiability. We know from a few sources that he loved merrymaking and had the heart of an adventurer, but there is no evidence that he actually indulged in vices. The tendency to portray him almost as if he were a villain can only be understood as intending to create a stark contrast to the post-conversion Francis. In truth, all we really know about the pre-conversion Francis, mostly from medieval transalpine legends, was that he was a rather outgoing young man who loved to be with people and who enjoyed poetry and music. In fact, he wanted to become a knight, and fought in two wars: a civil war in Assisi, and another one against the city-state of Perugia. In this second battle, he was captured and remained imprisoned for over a year.

He tried to convert the sultan.

During the Fifth Crusade, Francis traveled to Egypt to convert the Sultan Malik al-Kamil —Saladin’s own nephew. St. Bonaventure described the encounter:

“The sultan asked them by whom and why and in what capacity they had been sent, and how they got there; but Francis replied that they had been sent by God, not by men, to show him and his subjects the way of salvation and proclaim the truth of the Gospel message. When the sultan saw his enthusiasm and courage, he listened to him willingly and pressed him to stay with him.”

It is said that Francis greeted the Sultan with the greeting “may the Lord give you peace,” a formula the Sultan might have found familiar (“as-salaam alaykhum”). On the one hand, this is the classic greeting one finds in most epistles in the New Testament (Paul’s, Peter’s, and John’s) as well as in John’s Revelation. Moreover, Christ himself uses this very same salutation formula four times after his Resurrection, according to the gospels of Luke and John. But, on the other, the fact that we find this greeting written in Greek in the Gospels doesn’t mean it is a traditional Greek salutation only. In fact, “peace be with you” is a traditional Jewish and Arabic greeting (also commonly used by Arab Christians, both as a greeting and as a liturgical formula). In both languages, when one is greeted with “shalom aleichem” or “as-salaam alaykhum” (Hebrew and Arabic respectively for “peace be with you”), the proper, typical reply is “aleichem shalom” or “wa alaykumu as-salaam” (“and peace be upon you, too”), just as Christians reply “and with your spirit” in liturgical services. In fact, the Latin liturgical formula — which is drawn from the Latin Bible, the Vulgate — is even more similar to both the Hebrew and the Arabic, and is inspired by a passage found in Matthew 10:13 (“If the home is deserving, let your peace rest on it; if it is not, let your peace return to you”): it reads “pax vestra revertetur ad vos,”“may your peace return to you.” It is only natural Francis decided to use this greeting.

Though the Sultan did not convert, Francis and the Sultan became true friends. Ten years later, Al-Kamil freely gave Jerusalem to the Christians.

Francis’ grave was lost for years.

St. Francis died on October 3, 1226. On July 16, 1228, only two years after his death, he was pronounced a saint by Pope Gregory IX, the former cardinal Ugolino di Conti, who was friends with Francis and the Cardinal Protector of the Order. The very next day, the pope laid the foundation stone for the Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi. Construction began quickly. Francis was buried on May 25, 1230 under what is now the Lower Basilica, but his tomb was soon hidden on orders of Brother Elias (the third Minister General of the order, right after Peter Catani, who had succeeded Francis himself) to protect it from Saracen invaders. His burial place remained unknown, until it was rediscovered in 1818. Furthermore, it was not until 1978 when the remains were examined and confirmed by a commission of scholars appointed by Pope Paul VI, and put into a bronze urn in the ancient stone tomb.

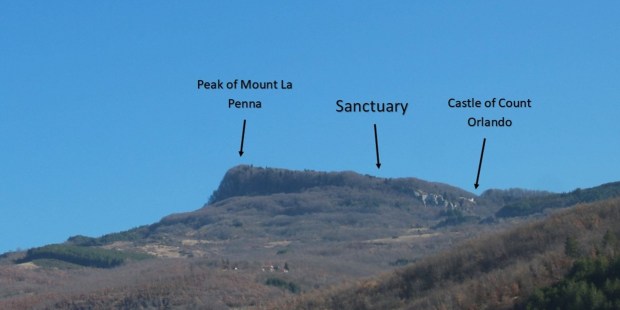

Be sure to view the slideshow below to discover the place where tradition claims St. Francis received the stigmata.