Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

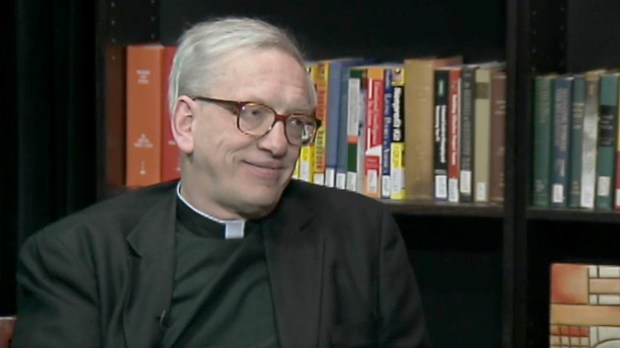

“You can still smell the fresh-baked grace,” Fr. Joseph Koterski said as he motioned to smell the aroma arising from his shoulder. The quip came as he told us he had recently been ordained a Jesuit priest. It was 1993 or so, and we sat in one of several cars headed out of Manhattan on a Friday night, on our way to a retreat house in upstate New York. The three or four of us in the car with Fr. Joe engaged in as much conversation as we could before entering into the “great silence” of a traditional Ignatian retreat.

Baking metaphors aside, Father’s reference to grace was timely. He displayed a sense of grace — in another sense of that word — as one member of our company seemed to have constant complaints regarding the road trip. While the driver muttered that the gentleman’s harping “strained charity,” Fr. Joe remained calm and tried to keep the conversation positive.

As we attended his retreat that weekend, we got a taste of the clarity for which Fr. Joe would become known, and his ability to put complicated matters in simple terms. He counseled us to “go with the fruit” when meditating on a Scripture passage. In other words, instead of dutifully getting to the end of a prescribed reading, if one line or word or image strikes your fancy at that particular moment, dwell on it and forget about the rest, for now.

In a one-on-one session, he commended me for not reacting disdainfully when someone making a private retreat on her own wanted to engage me in conversation at breakfast, not realizing that our group was on a silent retreat.

From the car ride and the experience with the loquacious retreatant, I came away from the retreat with a lesson on charity.

There would be other retreats with Fr. Joe, and a personal meeting with him for counsel. Because I lived and worked in New York City, I would have other opportunities to meet and hear him. Though his base was in the philosophy department at Fordham University, he started showing up in lots of other places, gracing the Catholic circles of the time. He gave a lecture series on St. Augustine’s Confessions through the Wethersfield Institute and taught a class on what was then the “new” Catechism of the Catholic Church, both of which I attended.

Thanks to certain friendships I had and circles I hung out in, I got invited to an informal group in people’s homes to read through Shakespeare plays, with each participant taking a role (or several, if the play had a larger cast), and all of us sitting down to dinner afterwards to discuss the themes of the work or to just chew the fat. Fr. Joe often told us about a book he’d been reading. He was always reading something.

Meanwhile, my older sister went back to college and ended up taking several courses with Fr. Joe. They were close in age, and became good friends.

In time, a new job took me out of New York, but I was still close enough to drive to the metropolitan area to attend a Shakespeare reading or show up at a dinner party where Fr. Joe often would be.

In late 2006, however, tragedy struck our family — an automobile accident taking the lives of my brother, his wife, and their 20-year-old son. Our Jesuit priest friend was a source of comfort and strength, and the philosophy professor and moral theologian part of him was a sure guide as we dealt with end-of-life matters. He offered to celebrate a memorial Mass for our three loved ones, an invitation he would repeat every year, for several years. Each year, the sting of loss was blunted just a bit, thanks in no small part to the friendship of Fr. Joe and his wise homilies, trying to make sense of tragic death.

After one of those anniversary Masses, as we were heading out for a meal in a local Italian restaurant, Fr. Joe beat me to the coat closet, grabbed my overcoat and motioned to put it on me.

More recently, as our mother aged and endured a couple of mishaps at home, rehab, and assorted health issues, Fr. Joe was always willing to come for a visit, to offer Mass, to hear her confession and bring her the Eucharist. And, as she lay dying in her bed at home, Fr. Joe said he would get there as soon as he could, to anoint her and bring her Viaticum. She took her exit as he was driving from Fordham, but still, he was there for her, blessing her lifeless body and praying for her soul on her final journey — and for us.

Nine months later, on August 9, with all of us assuming that we would have another chance to sit down to a meal with Fr. Joe, he suffered a fatal heart attack while attending an icon-writing workshop at St. Edmund’s Retreat House in Mystic, Connecticut. He was 67.

All of this might sound like a nice recounting of a simple relationship between an ordinary priest and an average Catholic family. It should be no surprise that a priest would tend to the spiritual needs of the flock, right? What’s the big deal?

Nothing, really. It’s just a priest being a priest, forgetting about himself and putting the faithful and their needs first and foremost in the many decisions he makes about what to do with his time.

Except that Fr. Joe had a full load of courses at Fordham, where he was once chairman of the philosophy department. Teaching, tutoring, grading, advising, as well as writing (Introduction to Medieval Philosophy: Some Basic Concepts was one of several books he published) and guiding doctoral students in the writing of their dissertations, would have been enough. But there was so much more.

He was master of Queen’s Court Residential College for freshmen, living in a dorm room and meeting with students several nights a week for something called Knight Court, where the freshmen enlightened one another — and Fr. Joe — with 10-minute presentations on favorite topics. Among the many ways Fr. Joe sought to instill Catholic values in them? Holding Shakespeare readings.

His academic work did not stop at the periphery of Fordham’s leafy campus. He also gave courses at St. Joseph’s Seminary in the Archdiocese of New York and in the friary of the Franciscans of the Renewal, where he had several priests and seminarians under spiritual direction. He was chaplain and teacher for the Sisters of Life and Missionaries of Charity in New York. He went to Haiti several times to preach a retreat for Mother Teresa’s nuns in Port-au-Prince. Often, when he came to one of the soirees my wife and I attended, he apologized for being late because he had just come from offering Mass in upper Manhattan — a longtime “gig” at a parish far from his Fordham residence — and then apologized for leaving before 10 because he had to get up early to say Sunday Mass at the Missionaries of Charity convent in the South Bronx.

Fr. Joe was instrumental in founding the organization University Faculty for Life. He was editor of the International Philosophical Quarterly. He served two terms as president of the Fellowship of Catholic Scholars. He was often flying off somewhere to give a course or a lecture, even as far as Hong Kong and Guam. He served on the boards of several universities and institutes, as well as on New York Cardinal Timothy Dolan’s Pro-Life Commission. He was a radio show host, a lecturer for the Great Courses series, and on and on. When his CV was last updated, in 2018, it stretched to 60 pages. He was a voracious reader who is said to have gone through a slew of Russian novels during the recent lockdown.

It occurred to me that he could have been one of these clerical “rock stars” whose eloquence and erudition — and sometimes polemics — attract a very large following. I wonder if he recoiled from such a thought because so many of them have fallen from grace, leaving their fans either disheartened or digging in even deeper against the powers that supposedly want to silence them.

Is that perhaps why Fr. Joe chose to spend whatever free time he had with the lowly and simple, such as us? Is that why he would “lower” himself to hold the coat of a younger man and let him slip his arms into its sleeves? Or roll up his own sleeves and help wash dishes in the midst of preaching a retreat for the Sisters of Life?

Nobody knows where he found the time, speculating that he slept very little. He certainly didn’t waste time with things like Facebook — he had virtually no social media presence.

He did have a presence to each person he encountered, however, and it’s striking that, in the wake of his death, so many people felt that they had had a friendship with him. A man with so many “things on his plate” could have been forgiven for turning down most of the demands on his time from average people.

But Fr. Joe was “a priest first and foremost,” Jesuit Fr. Christopher Cullen, a fellow philosophy professor at Fordham, said in the homily at Fr. Joe’s funeral last Tuesday. “He was filled with pastoral zeal that was built around a profound charity for the care of souls, each individual one at a time.”

I think we have a clue to what drove Fr. Joe, contained in a tribute he wrote for his friend, fellow Jesuit Fr. Paul Mankowski, who died in September 2020. The two men, similar in age, preached retreats together in Haiti.

In his First Things essay, Fr. Joe attempted to explain Fr. Mankowski’s approach to his Jesuit vocation by quoting from foundational documents of the Society of Jesus, in particular, The Formula of the Institute, which outlines the Society’s character as a “priestly community engaged in evangelization and in the spiritual consolation of the faithful.”

“It is by reference to these goals that decisions are made about how each man is to live and how the Society as a whole is to operate,” Fr. Joe wrote. It’s true, the Jesuits are known for their work in education: Fordham, Georgetown, Gonzaga, St. Louis University (his alma mater), etc. But schools, Fr. Joe clarified, were originally intended to be “a way to provide a means for both evangelization and the pastoral care of the faithful, especially by hearing confessions, giving spiritual direction, and conducting retreats.”

For Fr. Joe, his vocation to the priesthood came first, and that vocation is mostly exercised in small venues such as celebrating Mass and private sessions such as hearing confessions or giving spiritual direction. But it is also exercised through relationships between individual persons and friendships. Fr. Koterski has been described as a philosopher with a brilliant mind. I dare say, his brilliance allowed him to carry out his secondary vocation — teaching and writing — without the need for much more preparation than he already did in his formal studies. That left him time to carry out his primary vocation.

As we bid farewell to Joseph Walter Koterski in this Year of St. Joseph, in this Ignatian Year, may we learn well from the lesson that he made of his own life — a priest and a teacher who taught not just with eloquent words but also with the quiet resolve to be, in an oft-heard Jesuit expression, a man for others.

That fresh-baked grace never grew stale.