Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

The Italian city of Padua’s 14th-century frescoes are one of the more recent additions to the United Nations list of world heritage sites.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) voted in 2021 to add 34 places to its list of World Heritage Sites. They include the Colonies of Benevolence In Belgium/Netherlands, the Paseo del Prado and Buen Retiro in Spain, the Trans-Iranian Railway in Iran, and others.

UNESCO says that sites on the list must be of “outstanding universal value.”

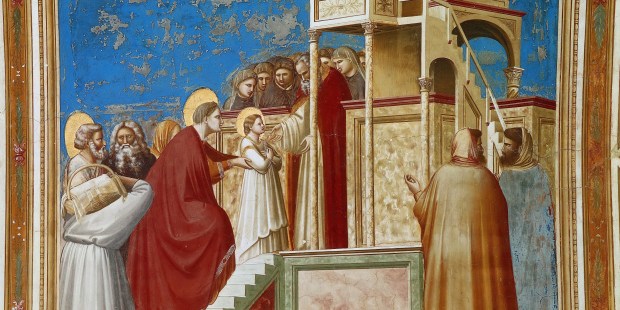

The “‘Padova Urbs picta” site is composed of eight religious and secular complexes within the historic walled city of Padua, which house a selection of fresco cycles painted between 1302 and 1397 by different artists. They include Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel fresco cycle, considered to have marked the beginning of a revolutionary development in the history of mural painting. As a group, the fresco cycles illustrate how, over the course of a century, fresco art developed along a new creative impetus and understanding of spatial representation.

The frescoes are found in the Scrovegni Chapel, the Church of the Eremitani, the Palazzo della Ragione, the Cathedral Baptistery, the Chapel of the Carraresi Palace, the Basilica and Monastery of St. Anthony of Padua, the Oratory of St. George and the Oratory of St. Michael. All are well conserved and open to the public.

They are all large-scale works with a complex narrative content. Giotto’s frescoes show his exploration of the possibilities of perspective and develop upon Giotto’s interest in the realistic portrayal of human feelings. In general, the frescoes work towards a trompe-l’oeil depiction of space, and there is innovation in the depiction of states of feeling.

“While in Padua over the years 1303-1305, Giotto would paint his absolute masterpiece: the frescoes of the Scrovegni Chapel, which is now also the best- known and best-preserved of all his fresco cycles,” according to the UNESCO website. “After having completed the fresco cycle in the Franciscan Basilica at Assisi, the artist had worked for Pope Boniface XIII in Rome and ultimately moved to Padua, where he developed new ideas that would rejuvenate the tradition of fresco painting.”

Another innovative feature in Giotto’s Scrovegni frescoes had been his attention to the depiction of human feelings and emotions, UNESCO said. “Never before had an artist shown such refinement in making each figure an individual, portrayed not solely as a physical body of defined volume and anatomy but also as a fully-fledged person whose reactions and feelings were captured with great psychological insight. Giotto was the first to attempt to people his scenes of biblical narrative with fully-rounded human beings, and this was another aspect of his art that would be developed upon in later fresco cycles within the city, in particular those by Jacopo Avanzi, Altichiero da Zevio and Jacopo da Verona.”

UNESCO continued:

Giotto’s work in Padua also marked the beginning of pictures that aimed to depict religious subjects within the context of everyday life and contemporary history — a tendency that in literature might be said to have begun with Dante’s Divina Commedia. When depicting scenes from the Bible, both Giotto and those who worked with him or after him would include not only saints and prophets, patriarchs and madonnas, but also recognizable contemporary figures and depictions of the clients who had commissioned the work.