Embarrassingly bad financial decisions are the least of the issues in a Vatican trial that opened July 27.

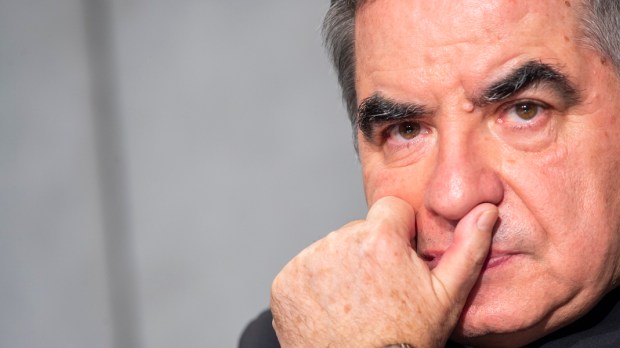

Cardinal Angelo Becciu, the former prefect of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, is one of 10 persons who were named in an indictment handed down earlier this month. Prosecutors allege a variety of charges against the defendants, including extortion, embezzlement, abuse of office and corruption, according to the Associated Press.

Becciu “will be the first cardinal prosecuted by the tribunal after Pope Francis changed Vatican law to allow laymen to judge cardinals,” AP said. Becciu has denied any wrongdoing.

“The idea of holding some of these people responsible seems to be a necessary thing for the Vatican,” said James Keating, associate professor of theology at Providence College, in an interview. That would prevent the Vatican and its Institute for the Works of Religion — commonly referred to at the Vatican Bank — from running afoul of external agencies that oversee financial institutions, to “make sure they’re not laundering money and that sort of thing.”

The trial also gives the Vatican a chance to demonstrate that real accountability is at work, Keating said. “That seems super obvious to me that that is a smart move. But opening up the possibility, unless you really checked it out, that these people can plausibly claim that the things they’re being charged for had been approved or at least they had reason to believe they were approved by people who were not indicted.”

The most obvious persons not indicted, he said, are those who worked in the Vatican’s Secretariat of State while the deal was being managed, including Cardinal Pietro Parolin, Secretary of State, and his deputy, Archbishop Edgar Pena] Parra. Keating said that could turn the trial into a “big mess” because the accused “can all say ‘We’re fall guys because Parolin and Parra are very close associates of Francis. That argument that it’s just the people Francis doesn’t like that are being charged has initial possibility.”

Even so, Keating is glad the Vatican is making a good effort to show that there are penalties for violations. “It’s not business as usual,” he commented. “Francis has said that there’s actually going to be accountability even if you’re a cardinal.”

Francis removed Becciu from his position last September on charges of nepotism.

“He is accused of that oldest of the Vatican problems, which is you use your power and access to Vatican funds to enrich your family members,” Keating said. “He denies all those things but now what he is being charged with is his role in this financial transaction and all the problems associated with it.”

Promising investment

The financial investment he referred to was a former warehouse for Harrods Department Store in London. “So it was a pretty big space and it’s in a swanky part of London, so it was seen as a great investment, well worth the €200 million they were going to pay for it,” Keating explained. “The idea was that it was going to be worth a lot more than that.”

It’s not immoral for the Vatican to invest its money — indeed, it has good reason to try to grow its funds in order to support its mission of evangelization and pastoral care around the world. The Holy See has rules about ethical investments. Pope Benedict XVI pushed hard for such guidelines, Keating noted. The more challenging task is to determine who the Vatican is going to use in order to broker deals. In this case, which ended up losing a lot of money for the Vatican, there are charges that outside experts duped the Vatican or even embezzled money and extorted Vatican officials.

In 2014, the Secretariat of State invested more than 200 million euros in a fund run by Italian investment broker Raffaele Mincione, securing about 45% of a commercial and residential building in London. Mincione is accused of deceiving the Vatican. In 2018 the Vatican tried to end its relationship with Mincione and turned to Italian investment broker Gianluigi Torzi for help in buying up the rest of the building. But later, the Vatican accused him of extortion.

“What Vatican prosecutors found was that the two people they were working with turn out to be kind of scummy guys, who were bilking the Secretariat of State or the Vatican Bank for exorbitant fees,” Keating explained. “They were playing games with them and all sorts of things like that.”

Both of the men have denied wrongdoing.

At the time, Becciu was deputy secretary of state for general affairs, given responsibility for handling hundreds of millions of euros. He is charged with five counts of embezzlement, two of abuse of office, and one of inducing a witness to perjury. He is also charged with allegedly funneling money and contracts to companies or charitable organizations controlled by his brothers in Sardinia.

Another Sardinian, Cecilia Marogna, 40, a woman who worked for Cardinal Becciu, was charged with embezzlement. She has denied wrongdoing.

Defendants face fines and/or prison time if convicted. After an initial hearing July 27, the proceedings are being postponed until October 5, as most public institutions in Italy are closed in August.

“I think the easiest way to think of this trial is that it’s the Vatican’s response to this complaint, which is an old one but has recently revived, that it has no accountability structure, that no one ever suffers (consequences),” Keating remarked. “They decided — the Vatican prosecutors, that is, I’m sure with Francis — that they’re going to change that.”