Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

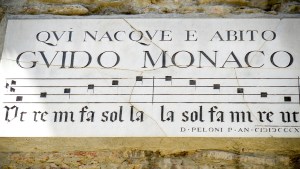

The musical notation we still use today was born in the eleventh century in the 11th century in Pomposa, near the Italian Adriatic shore. It was then that Benedictine music theorist Guido D’Arezzo noticed his fellow monks had difficulties remembering the melodies they were supposed to sing while praying the liturgy.

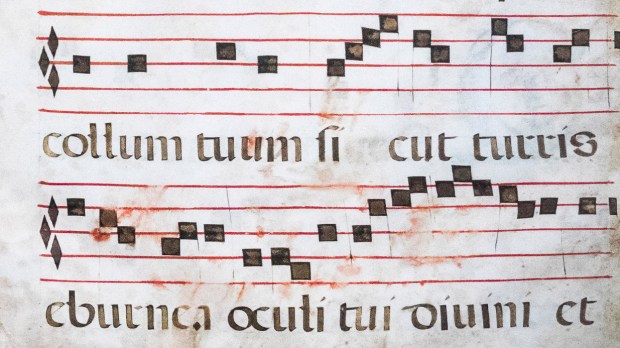

Arezzo’s system is relatively simple. It is based on a five-line staff, with four spaces and seven notes that can be located in different octaves —with a few extra details here and there: some other symbols for different keys, others for semitones. It replaced pneumatic notation, which just included some relatively vague indications regarding pitch and rhythm patterns. These instructions would allow the singer to follow the needed changes in articulation, duration, or tempo as related to their own breathing capacities —the word pneumatic derives from the Greek pneuma, meaning “breath.”

Since then, liturgical music has been written in a myriad of different styles, from intricate baroque patterns like those of Johann Sebastian Bach to minimalist settings such as those of Arvo Pärt. Here, we include four unique settings of the Latin Mass you might not have heard before.

1. Missa Luba:

The Missa Luba is a unique setting of the Latin Mass, sung in styles that are traditional to the Democratic Republic of Congo. The Kyrie, for instance, is in the style of a kasala (a Luba song of mourning) and the Sanctus and the Benedictus are inspired by Bantu farewell songs. In its day, it was the most successful of many different Masses created around the 1950s and 1960s, becoming even more popular than the 1964 Misa Criolla and the 1966 Misa Flamenca.

The Missa Luba (Luba being an ethno-linguistic group indigenous to the Congolese south-central region) was composed by the Belgian Franciscan priest Guido Haazen. It was originally performed and recorded in March 1958 by Les Troubadours du Roi Baudouin (King Baudoin’s Troubadours), a choir of adults and children from the Congolese town of Kamina.

2. Misa Flamenca:

Francisco “Paco” Peña was born in Córdoba (Spain) in 1942. When he turned six, his brother taught him how to play the guitar. It would only take him six more years to make his first professional appearance. A brilliant musical career took him from Madrid to London, where he became a soloist in 1960.

While in England, he generated so much interest among the British audience (who might have never been acquainted with flamenco) that he soon found himself sharing the stage with Jimi Hendrix, playing in the Royal Albert Hall, and Carnegie Hall. One of his famous compositions is his Misa Flamenca —a whole flamenco Mass, including a Gloria and renditions of the Creed and the Lord’s Prayer.

3. Misa Criolla:

Ariel Ramírez began teaching in a rural mountain post when he was just 19 years old. There, he became fascinated with the sheer diversity of South American traditional music —a combination of aboriginal, gaucho, and creole tunes. He then studied folk traditions formally at the Academy of Vienna and the Institute of Hispanic Culture in Madrid in the early 1950s.

Right after the Second Vatican Council authorized vernacular Mass settings, Ramírez created his widely popular Misa Criolla on a Spanish translation of the traditional liturgical text, including folkloric interpolations in it. Each movement of this Mass is based on specific folk material. Ramírez used, for example, the stern and severe rhythm of the northern Argentinian vidala for the Kyrie, and the more joyful carnavalito for the Gloria.

4. To Hope! A Celebration!

Trained as a classical musician, Dave Brubeck’s improvisational skills made him one of the most prominent exponents of cool jazz —a subgenre that, unlike bebop, is characterized by relatively lighter tones and more relaxed tempos.

Even if almost everyone is familiar with some of his jazz standards, relatively less known are his orchestral and sacred music works, including his rendition of the Mass in the Revised Roman Ritual, called “To Hope! A Celebration!” It was originally released in 1980, featuring Brubeck himself on the piano, the Cincinnati May Festival Chorus, and the Mt. Washington Presbyterian Church Handbell Choir. The Mass had been commissioned by Ed Murray (then the editor of Our Sunday Visitor) who played a central role in Brubeck’s own conversion.

Brubeck became a Catholic in 1980, shortly after completing this Mass. Although he surely had some spiritual anxieties and inclinations before his conversion, he famously said, “I didn’t convert to Catholicism, because I wasn’t anything to convert from. I just joined the Catholic Church.”