Since the Vatican is a monarchy governed by a sovereign elected for life, the matter of the sovereign’s health is particularly sensitive. This is currently the case, as Pope Francis was hospitalized on June 7, 2023 to undergo an operation under general anesthesia. Fortunately, he is recuperating well and his life is not apparently in danger. However, this episode, as with previous hospitalizations, raises a question that has been recurrent in recent years and for the moment is still unresolved. Who governs the Holy See when the pope can no longer govern?

When a pope dies, things are very clear from a canonical point of view: power is entrusted, during the period of vacancy, to the camerlengo. This person, a cardinal chosen beforehand by the pontiff, then takes charge of ongoing affairs until the election of the new pope. Today, if Pope Francis were to die, the current camerlengo—American Cardinal Kevin Farrell—would hold the reins of the world’s smallest state for a few days.

But canon law does not provide for everything. There’s a grey area from the moment the pope checks into the hospital. In this case, the Pontiff has been fully aware except during his anesthesia and the question of governance has barely arisen: nothing has changed. The Pope continues his mission “even from a hospital bed,” said Card. Pietro Parolin, Secretary of State of the Holy See, on June 7. He assured reporters that no delegation of power was foreseen, even during his anesthesia.

A pope cannot be declared “incapacitated”

But what would happen if a pontiff were to end up in a coma, for example, or suffer from a chronic mental incapacity to govern? What if the pope became physically or mentally unable to govern, but also unable to renounce?

The pope “is the only one who can freely renounce his power,” says a canonist who spoke with Aleteia. As the Jesuit website America reminds us, canon law has provisions for when bishops are “incapacitated.” It allows them to be removed from responsibility for their diocese in the event of “captivity, banishment, exile or incapacity.” The auxiliary bishop or vicar general then takes over the diocese until a successor is appointed. If this canon were applied to the case of the pope, considering that he is bishop of Rome, it would mean that his vicar for the diocese, Cardinal Angelo De Donatis, would have to take over.

However, the Bishop of Rome is not a bishop like any other, as canon 335 indicates. This legislative text provides for cases where the Holy See finds itself “vacant or entirely impeded.” However, in such a situation, “nothing can be altered in the governance of the Church” during such a period.

A problem of increasing relevance

The question of a pope’s inability to govern is in fact a real “loophole” in canon law, according to a canonist who has worked on the issue at the highest level and prefers to remain anonymous. “Theoretically, we don’t have the criteria to prevent a pope from being unable to govern.” As a result, if the situation arose, jurists would have to “interpret” the few existing elements in order to find a solution.

This conundrum has been a concern for many of Pope Francis’ predecessors, especially the popes who came after World War II—the main reason being the significant increase in their lifespan due to medical advances during those years. However, medical incapacity was not the only possible scenario considered by a pontiff.

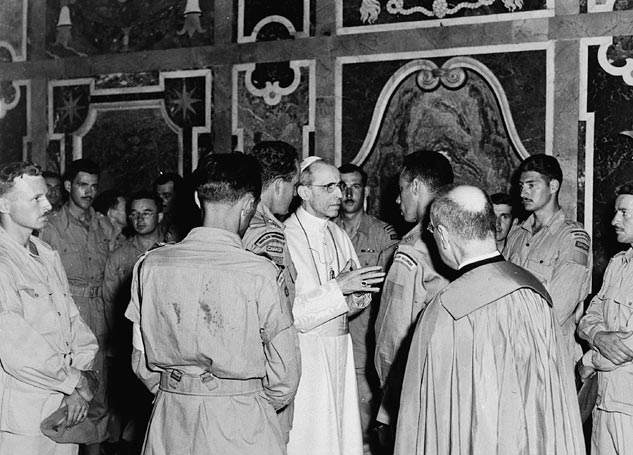

Pius XII: “They’ll take Cardinal Pacelli, not the pope”

No doubt remembering the dramatic kidnappings of Popes Pius VI and Pius VII during the French Revolution, Pius XII considered the question of incapacity to govern. Locked in the Vatican during World War II, the pontiff had indeed taken very seriously the risk he would run in the face of the Nazi threat.

According to his Substitute of the Secretary of State, Cardinal Domenico Tardini, the pope had put in place precise countermeasures in the event that the Third Reich came to target him directly. In particular, he reportedly prepared a letter in which he declared his resignation, giving instructions for the cardinals to elect his successor. “If they kidnap me,” the pope is said to have declared, “they will take Cardinal Pacelli, but not the pope.”

The precautions of Pius XII were far from superfluous. Indeed, when Mussolini, under pressure from the Allies, was overthrown by the Italian people in 1943, the Germans hatched a plan to kidnap and assassinate the head of the Catholic Church, but failed to carry it out.

Paul VI’s letter

Historian Roberto Rusconi reports that the question of incapacity was also considered by Pius XII’s successor, John XXIII. The “good pope” wondered during his pontificate about the possibility of renouncing because of his precarious state of health, affected by the heavy task of the Second Vatican Council.

The next pope, Paul VI, had publicly ruled out the possibility of renouncing. Nevertheless, in 1965 he wrote several letters to the dean of the College of Cardinals in which he considered the possibility that, if he were to fall into a coma or suffer from dementia and thus be unable to renounce, he might replaced, after a new conclave, by another pope.

These letters have no legal value, although they are part of the “informal magisterium” of the former pontiff, explains the canonist interviewed by I.MEDIA. The correspondence was unearthed long after his death, but there is no reason to believe that it would have triggered a vacancy if the Italian pope had been incapacitated.

Benedict XVI’s canon law project

The pope most concerned by this possibility was Benedict XVI. In 2005, the German pontiff was deeply affected by the long agony of John Paul II during the final years of his pontificate. Being in a position very close to the pontiff, he witnessed this period of instability, particularly from the point of view of Church governance. This prompted him to think of some solutions.

He reportedly asked Cardinal Julian Herranz, then President of the Pontifical Council for Legislative Texts, to draft a canon to fill the existing legal vacuum. The task was completed. The result provided that the College of Cardinals, convened by its dean, could declare a state of impediment. According to this project, after conducting an inquiry and consulting medical experts, the cardinals would have the authority to solemnly end the pontificate and open the traditional period of vacancy of power with a view to a conclave.

However, although the canon was presented to the head of the Catholic Church at the time, it was never promulgated. Benedict XVI didn’t need it, however: he found another answer to the question he was asking himself.

Preemptive renunciation

Because he feared he would be unable to govern due to his frail health, the 265th pope finally decided, to everyone’s astonishment, to preemptively renounce the Petrine ministry in 2013.

In an interview with his biographer Peter Seewald, he confirmed that it was indeed the question of his health–including his inability to undertake long journeys, in particular the World Youth Day planned for Brazil in the summer of 2013–that made him decide to end his pontificate.

Benedict XVI’s “preventive renunciation” was a roundabout way of responding to the legal conundrum of a pontiff being incapacitated. The professor of canon law who spoke with Aleteia confirms that the “legal vacuum” remains unresolved. “If such a situation were to arise, we’d be in uncharted waters,” he concludes.

Pope Francis’ surgeries

During his operation on June 7, 2023, Pope Francis had to undergo general anesthesia, even though he had said he didn’t want to have recourse to it after his previous colon operation in 2021.

After successfully operating on the pontiff for the second time, surgeon Sergio Alfieri insisted that the pope had nothing per se against general anesthesia, but explained that “nobody likes to be put to sleep.”

The problem, for Francis, could be a legal one. “There is no possibility of declaring incapacity, as is the case in American law, for example,” explains the canonist. The President of the United States, if anesthetized, temporarily cedes his power to the Vice-President. Something similar happens in some other countries. In constitutional law, the procedure of declaring incapacity concerns an elected person. While the Pope is indeed elected by the College of Cardinals, it is his “acceptance” of his election, and therefore of the action of the Holy Spirit, that confers his power, “not his election.”

Consequently, during the three hours of anesthesia the Holy See was under the authority of the Pope, even though he was totally incapable of making a decision if necessary.

Pope Francis’ letter of renunciation

Francis knows the risk of such a situation if it lasts longer. Last January, shortly after the death of Benedict XVI, he revealed that he had followed the example of Paul VI and Pius XII and, back in 2013, had drafted a letter of resignation to be used in the event he were incapacitated.

He gave it to Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, then Secretary of State of the Holy See, who then passed it on to Cardinal Pietro Parolin when the latter succeeded the Salesian in October 2013. However, the conditions for its use are unclear–and by no means laid down in canon law. “It would probably be necessary for the Secretary of State to have the letter accepted by the College of Cardinals,” says the canonist.

In an interview with I.MEDIA, a cardinal very close to the Pope said that he considers, however, that it would be “very complicated” for the cardinals to take the decision to depose a Pope who would no longer have the capacity to govern, even with this letter.