The Christian understanding of the sacrament of matrimony developed slowly in the early Church, and the value of marriage often played second fiddle to celibate ministry. Jesus chose a wedding for the scene of his first miracle and He was clear that marriage was indissoluble and inviolate, yet the structure of the sacrament took centuries to consolidate. Roman law and an optional priestly blessing served for marriage in the Empire and after its dissolution, the Church stepped in, but without a standardized rite or body of teaching. Meanwhile, the dogma of the Virgin birth overshadowed St. Joseph’s role as Mary’s husband and Jesus’s foster father, leading St. Jerome to hold Joseph up principally as having “always preserved his virginal chastity.” Art reflected these emphases by either omitting St. Joseph from the scene or depicting him as an elderly man, safely beyond the lustful desires of youth.

St. Joseph: The face of the model marriage

St. Augustine stepped in to argue for the goods of marriage, insisting that it provided for procreation of children, contained concupiscence, and fostered companionship between the two sexes. Little did the Bishop of Hippo know that St. Joseph would wind up being the face of the model marriage.

Medieval matrimony was mired in confusion. Clandestine marriages abounded — a bane of bishops, for without witnesses, problems of polygamy proliferated. The Fourth Lateran council in 1217 attempted to reign in abuses by requiring the public reading of marriage banns.

Furthermore, the word “matrimony,” derived from the Latin words for “mother” and “state of being,” led many to believe that procreation, and therefore consummation, was what constituted a marriage. In rebuttal, St. Raymond de Peñafort penned a Summa on Marriage, acknowledging the importance of consummation but stating that “marriage is contracted by consent alone.”

Who better to illustrate consent over consummation than St. Joseph? And thus Raymond pointed out: “If it were understood of consent to carnal copulation, there would not have been marriage between Mary and Joseph.”

The perfect bridegroom as expressed in art

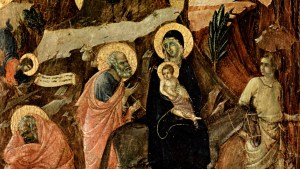

This line of thinking gave birth to a new iconographic theme to stimulate painterly creativity: Joseph the perfect bridegroom. Giotto, the pioneering 14th-century painter, was among the first to depict the wedding of Joseph and Mary in the Scrovegni Chapel. His mastery of light lent the figures presence, while his attempts to create a three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface showed viewers a bride and groom entering into a sacred space for the sacrament. Numerous witnesses are present, watching as the priest guides the hands of Mary and Joseph together, underscoring their consent. Outside. a group of men break branches and confer angrily, a nod to the apocryphal story where Mary’s suitors carried wooden rods in the hopes of being chosen. When Joseph, mocked by the youths for his age, came forward, his branch flowered, signifying his divine selection, and the young men snapped their twigs in angry disappointment.

The enigmatic young man standing with his hand raised at the doorway is more easily understood in a later version by Giotto’s student Bernardino Daddi, who set his wedding scene in a delightful enclosure, surrounded by floral tapestries. The women cast admiring glances at the Virgin while the men gesticulate in anger, one raising his hand menacingly behind Joseph. It appears that one of the rejected suitors wants to reclaim his honor through blows, not an uncommon occurrence in Italy.

The discovery of the relic of Mary’s wedding ring saw the subject of the wedding nuptials graduate from small predella panel to altarpiece. It appeared in the city of Chiusi outside Siena, and increasing devotion called for a feast day to celebrate the Espousals of the Virgin, championed by Jean Gerson at the University of Paris, an author of an epic poem to Joseph.

The ring was stolen by a disgruntled German friar in 1473 and brought to Perugia, where it remains to this day. Shortly thereafter, Pope Sixtus IV, at long last, gave St. Joseph his own feast day, March 19.

In thanksgiving, citizens of Perugia commissioned their greatest artistic son, Pietro Perugino, to produce an altarpiece of the nuptials, raising the subject from predella scene to focal point. Perugino’s Marriage of the Virgin marked the triumph of Renaissance order and perspective. In the foreground, five men and five women line up daintily on either side of the couple. A man and a woman turn away from the viewer and toward the scene, inviting the faithful to participate as witnesses as Mary extends her finger to Joseph who proffers the ring. The large paving stones create an atmosphere of calm, and even the angry young men seem subdued. Perugino omits any excess of passion in the scene, invoking the chaste marriage without resorting to a geriatric Joseph. A fanciful eight-sided building, traditionally associated with baptisteries, presides over the scene, underscoring the sacramental nature of marriage, but also alluding to the impending birth of the Savior. All the receding perspective lines meet at a single point: the open doorway leading out into an endless horizon, an effective way of using the science of painting to express the permanence of marriage.

Four years later, Raphael produced an altarpiece of the same theme and style for the town of Città del Castello. The genius from Urbino was clearly inspired by Perugino but added a few special flourishes of his own. The elegantly proportioned piazza remained the same, but instead of the figures standing almost flush along the base of the picture plane, they circle gently inwards, inviting the viewer to join in the nuptial celebration. Raphael’s deeper colors add greater sobriety to the scene, and the space appears more expansive behind the wedding party. Raphael narrowed the age gap between Mary and Joseph, depicting a younger man, who will become a model of self-mastery in later works. Raphael’s two greatest innovations, however, were in the tilted head of the priest, forcing a stronger focus on the ring, and the rounded temple in the background, where the circular form not only suggests the infinite, but also the ring itself.

St. Joseph’s transformation was complete by 1523, when Rosso Fiorentino painted the Nuptials for the basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence. The patron, who had lost his heirs, dedicated a chapel to St. Joseph, a novelty in itself. The crowded scene takes place amid a lovely play of shadow and color, the light concentrating on the newlyweds in the center. Mary, demure, puts forth her elongated fingers, while Joseph, youthful, with muscular legs and a cascade of strawberry blond curls, pledges his troth. The strikingly handsome Joseph appears to amaze the priest, who gazes at him in admiration.

Three saints attend the nuptials: St. Apollonia (a Florentine favorite), St. Anne (Mary’s mother and the patroness of childlessness), and St. Vincent Ferrer, a patron of marriage. The profoundly personal nature of this devotional work presaged the increasing devotion to St Joseph that would be propelled by saints and that would launch numerous new images of the Renaissance’s Mr. Right.

Read the rest of our series of articles by the art historian Elizabeth Lev on St. Joseph in art:

Read more:

St. Joseph in art: An enigmatic and elusive figure

Read more:

St. Joseph in art: The silent knight

Read more:

St. Joseph in art: “Fool” for Christ