We cannot celebrate Easter without first crossing the desert. This is not just a Lenten image, but a fundamental truth of our life that has nothing to do with the idea of engaging in a humiliating penance as an end in itself: In order to rise again, we must let many things die.

There is a place we must cross, and it is our interior, the things that move within us, the wild beasts of our fears, our feelings of guilt, the anxieties, the things that make us angry, and the conflicts that agitate us. As we pass through this desert, we can examine everything, reject the bad, keep what is good, and put order in the chaos of our emotions and in the inner confusion that often prevents us from being clear-headed.

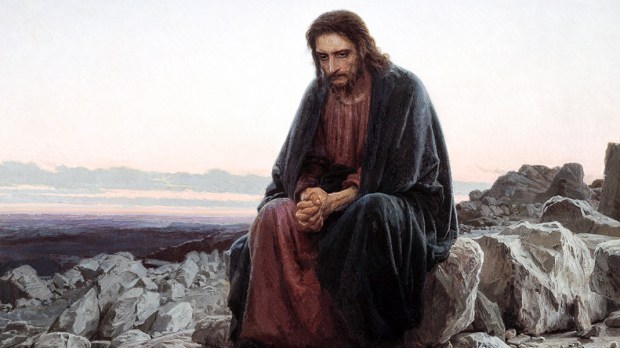

Here then is the desert: time for silence, for a severe but fundamental “face to face” with who we really are, for a dramatic but compelling struggle against what would like to enslave us. It’s a time for an unprecedented possibility that is granted to us every Lent: to free our freedom. To free it from the inner chains and from the human, social and cultural conditioning that surrounds us. Time to silence illusions and give space and voice to our deepest desires, to the thirst for life that we carry within us which, by our continuing to drink from “cracked cisterns,” remains unquenched.

Three verbs and three friends

First of all, “stop.” The desert is a necessary and regenerating pause. We need it to stop the race, pause, reorder our inner world, our priorities, the affections that govern our relationships, and so on. Cardinal Martini wrote: “Without our realizing it, life becomes disordered, fragmented, worn out. We need to put back in order the little pieces of our time, of our body, of our heart.”

The second verb: “struggle.” The Bible shows us that the desert is also a place of struggle, of trial, of temptation where we take the measure of ourselves. Here, we make war and then peace with our frailty and receive the grace of discernment that makes us better able to read life.

The desert is the place of crisis, and we’re called to bless the crises of our life, and our life that goes into crisis: it’s precisely at that moment, in fact, that something happens, that certain deadly things within us break down, or certain tired habits that restrict our life. The crisis can be a providential time: through what is put into crisis, God speaks to us and calls us to change.

From many crises, even small ones, we are reborn in a new way. Pope Francis has even said that a crisis is the work of God’s grace, and that we should look at it with the eyes of faith. In the desert, as we read in the biblical story, our certainties, our images, the fixation of our mental frameworks and ideas go into crisis: we find ourselves in an empty space, without reference points and without “road signs,” and we’re therefore obliged to look for other directions and other roads. We are called to imagine our lives in a new way.

Finally, the last verb: “love.” The desert is also a place of falling in love, where, stripped of everything, you walk, entrusting yourself and walking, to find true love, the love that nourishes your life. This is what the Lord says through the mouth of the prophet Hosea: “Behold, I will draw her to me, I will lead her into the desert and I will speak to her heart. There she will answer me as in the days of her youth.”

We need our love to be continually regenerated and renewed, leaving behind the temptation of habit and the risk of becoming a formal, external, worn-out, even unhealthy love. This applies to God and to the people we love. This is also what Lent is for: to look at our heart, to purify it, to make it return to the days of our youth by renewing the essential loves of our lives—above all, that for the Lord.

For this reason, God chooses to draw us to Himself and leads us into the desert, where, far from the noise and alone with ourselves, we can return to the essential: His presence as the foundation of our lives, and the people we have beside us, who love us and whom we love.

But we are not alone on this journey through the desert. We are accompanied by those who know more than we do, by some of the great biblical characters who know something more about the desert because they have crossed it, breathed, suffered, lived in it and also loved it. Because something important for their lives happened there and they would like to tell us that the same can also happen to us.

Let us make three stops in the desert: one with Moses, one with Elijah, and one with Jesus: precisely the three “friends” who are also on the Mount Tabor during the Transfiguration. Because the Lenten desert serves us for one thing only: to transfigure ourselves and rise again; to make Easter a reality in our lives, with the Risen Christ.

Read more:

A royal summons to the Cross of Christ