Faith and charity were the two forces that drove Jérôme Lejeune, the French physician who discovered the genetic underpinnings of Down syndrome, said the woman overseeing the movement to declare him a saint.

Aude Dugast, the Paris-based postulator of the cause of canonization of Jérôme Lejeune, spoke with Aleteia Wednesday, days after Pope Francis approved a key step advancing that cause. On January 21, the pope authorized the Congregation for the Causes of Saints to promulgate a decree concerning the heroic virtues of Lejeune. He now will be referred to as Venerable Jérôme Lejeune.

Dugast did not know Lejeune personally, though she admitted that he might have spoken at her university when she was growing up in Paris. But she has learned much about him since going to work at the Jérôme Lejeune Foundation in the French capital, then becoming vice postulator of the sainthood cause in 2007 and postulator in 2012. She oversaw the examination of his writings and coordinated the taking of testimony by those who knew him. Finally, she wrote the positio, a 1,000-page document detailing Lejeune’s life and virtues in support of his canonization.

“For me the main thing is his faith and his charity — a very strong and beautiful faith,” she said. “He never had doubts. He was a famous scientist, a genius, but he never saw any conflict between faith and science.Science helped him know creation, and faith helped him understand creation and to understand God. He showed there is no contradiction between these two kinds of knowledge.”

The profession in which Lejeune worked very often would pit intelligence against faith, but “he was the opposite,” Dugast said.

His other strong quality was his “incredible charity,” she attested. “He loved his patients. There were so many mothers who said they were very moved when they met him the first time and Lejeune looked at their son or daughter, and they saw that he looked at them with so much love in their eyes that they were very surprised, because he was a very famous professor. They were afraid to come with their child to this hospital, … but it was the first time they saw someone who was full of love for the child, and each time it was a new start for the family.”

He stood with science

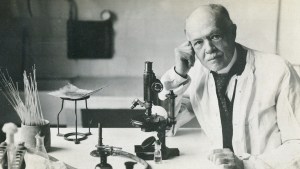

Lejeune was born in 1926 in the Paris suburb of Montrouge. He studied medicine, then became a researcher at the National Center for Scientific Research in 1952. In July 1958, assisted by Marthe Gautier, he established a link between a state of mental debility and a chromosomal aberration, by the presence of an extra chromosome on the 21st pair, thus discovering trisomy 21.

This caused a revolution in the thinking of the time. As Jason Jones and John Zmirak have written, the families of Down syndrome children for decades had lived under a false moral stigma, since it was widely believed that the child’s “retardation” was the side-effect of syphilis in the mother, which was associated in the popular mind with prostitution.

“By offering rock-solid proof of a biological cause for Down syndrome, Lejeune helped the parents of such children move in from out of the shadows,” Jones and Zmirak wrote. But he didn’t stop there, as they documented:

Lejeune went on to uncover the genetic basis for another devastating birth defect, Cri-du-Chat Syndrome, and made advances in understanding the causes of Fragile-X Syndrome. He also anticipated the rest of medical science by decades in his insistence on the importance of folic acid in reducing the risk of many birth defects.

Dugast concluded, “I think this love for the patient is really the explanation of all his life.He could have worked on so many other subjects — math, physics — and sometimes he wanted to do that. He would write in his diary, ‘Every time I wanted to work on something else, I had a mother or a patient who told me, Professor, we need you to find a treatment.’ And so he always decided, ‘I can’t go away to other things, because my patients need me.’”

Prophet in his own profession

To his horror, Lejeune’s research began to be used for purposes he disapproved of, such as early detection of trisomy 21 in embryos, leading to their abortion. He decided to publicly defend Down children by fighting against abortion.

“He could do no other than defend his patients,” Dugast said. “He knew they can’t defend themselves.”

And this is where his living out the virtues in a heroic way — a key element in the Church’s decision on whether or not someone can be declared a saint — is so evident for Dugast. Lejeune could have quietly continued in his research and his treatment of patients, without participating in abortion himself. But he felt compelled to speak out, even at the risk of being shunned by the profession.

“The main example for me is when he went to San Francisco in 1969 to receive the Allan Award,” said Dugast, referring to the William Allan Memorial Award of the American Society of Human Genetics. The award ceremony would include a major speech by the recipient, and Lejeune knew that his audience would include “the most important geneticists in the world,” she said.

“He decided that day to say clearly that medicine had to decide if it wanted to kill or cure,” the postulator said. “He knew that in doing that he could lose everything. But he felt that maybe there was an opportunity for these geneticists to change their mind.”

In fact, it has been widely reported that Lejeune later told his wife, “Today, I lost my Nobel Prize in medicine.”

“It was very courageous, and for me it was really the first heroic decision, because he could have decided to be a very ethical physician, never do abortions or anything against his patients, but without talking, without saying anything, without having any program. But he knew he had to speak out. The danger for him was not to not do abortions, but to talk and to tell the truth.”

A year or two after the Allan lecture, it was evident that Lejeune had become almost a persona non grata.

“He didn’t get invitations to any scientific congresses,” Dugast said. “Before this he was the geneticist everyone wanted to invite.”

But he wasn’t totally out in the cold. Pope St. Paul VI appointed him to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in 1974. He was also a member of the French Academy of Moral and Political Sciences, and of the Academy of Medicine.

Appointed by Pope St. John Paul II in February 1994 to head the new Pontifical Academy for Life, Lejeune died two months later, on April 3, which was Easter Sunday that year.

Today the Jérôme Lejeune Foundation continues its work of care and research, in France, Spain and the United States.

Read more:

What is it like being Catholic and a scientist?

Read more:

Washington Bioethics Summit Considers the Ethics of Gene-Editing