It is not hard to imagine that on Christmas night, St. Joseph too felt ill-prepared.

It wasn’t his fault, of course. A census had upset the couple’s birth plan, but surely he must have felt that the big day had arrived and he wasn’t ready for it — that he had a mission to do as a husband and father and, despite his best efforts, he wasn’t succeeding at it.

Did he choke back manly tears of desperation when he reported back to Mary that there was no room at the inn? Did Mary, ever-sinless, do what she could to assuage his frustration, but find herself unable to do much?

The couple had to settle for a makeshift solution, to be sure, but it was better than nothing. And Joseph undoubtedly did what he could to create a space as suitable as possible. Still it was last minute and sorely lacking … not at all what he would have dreamed of three weeks ago, at the start of his own first Advent.

Yet upon this scene entered the Word made Flesh, the tiny Merciful One.

Our own unreadiness

We don’t face the practical responsibilities that Joseph faced that night. Our feelings of inadequacy and ill-preparedness for Christmas will not have a direct consequence on the Birth.

But even if our reality is different, perhaps many of us do share the same sentiments Joseph felt. What do we do with that, now that Advent is basically over and Christmas is upon us, ready or not? What do we do with our weakness?

The stable suggests that we should let God turn it to good.

One of the truly awe-inspiring facets of the power of God’s mercy is how soundly he is able to claim victory over evil. Suffering and death entered the world through sin, so it is precisely through suffering and death that God brings salvation.

We might say that God wrests Satan’s own weapons from him, and turns them around to vanquish their owner, in the process enshrouding the very weapons in light. In other words, sin, weakness, death — the consequences of the devil’s work — can become the tools of God’s grace.

This is why St. Paul can say, “We know that in everything, God works for good” (Romans 8:28). And why the Catechism explains that “Christ’s inexpressible grace gave us blessings better than those the demon’s envy had taken away. … There is nothing to prevent human nature’s being raised up to something greater, even after sin; God permits evil in order to draw forth some greater good” (CCC 412).

Read more:

Pope: Christmas with restrictions? Mary and Joseph’s Christmas wasn’t a rose garden

In the stable

If we place ourselves in contemplation beside Joseph in the stable, perhaps we can find in the animals — with their accompanying stench — symbols of the many vices that we’ve no choice but to bring to the Christ Child this Christmas. Not that we wanted to bring him such “gifts,” but in our weakness, sin is what we can give him. Our unreadiness for this great feast is all we have.

Washed in the mercy of this tiny infant, though, these very animals have come to be a great contribution to the wee Child.

Artists depict the warmth of their breath shielding his sweet head from the cold. Benedict XVI considered them even as “an image of a hitherto blind humanity which now, before the child, before God’s humble self-manifestation in the stable, has learned to recognize him.” (The Pope Emeritus has a page-long reflection on the symbolism of the ox and ass in Jesus of Nazareth: The Infancy Narratives, 69.)

So our ill-preparedness is sufficient gift to him, and to give that gift we don’t need Advent to magically stretch any longer.

The experience of his mercy gives energy and serenity for these last few hours of Advent, warding off any temptation to sulk in remorse or needless worry. Let us humbly accept our unreadiness and lack of preparation, and let that be — with the ox and ass — the gift we offer him. If the poverty of our Advent leads us to turn our gaze to the Baby, then once again, God will have turned weakness to strength, and all things to good.

Read more:

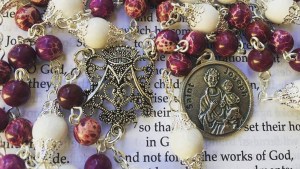

Try the Joseph Rosary