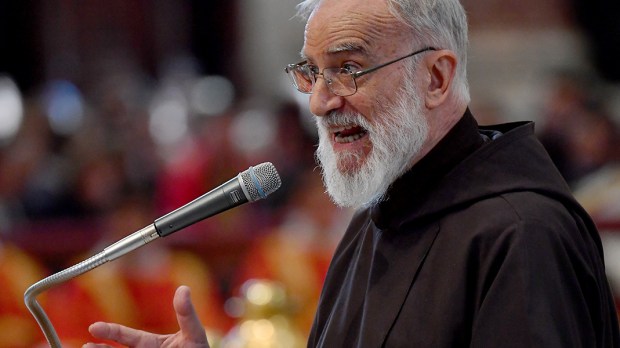

Cardinal Raniero Cantalamessa, preacher of the Pontifical Household, delivered the first Advent sermon of 2020 on December 4:

~

An Italian poet, Giuseppe Ungaretti, expressed the state of mind of soldiers in the trenches during the First World War with a poem of only ten words

We are

Like in autumn

The leaves

On the trees.

At this time in our lives, the whole of humanity is experiencing this same sense of precariousness and uncertainty due to the corona virus pandemic.

‘The Lord – as Saint Gregory the Great wrote – sometimes instructs us with words, while sometimes he does so with facts.’ In the year marked by the great and dreadful ‘fact’ of the corona virus, we strive to draw from it the teaching that each of us can draw for our own personal and spiritual live. We can only share this kind of reflections amongst us believers, as it would be a little unwise to propose them to all without distinction, lest it should increase the uneasiness towards faith in God that the pandemic produces in some people.

The eternal truths we wish to focus on in our reflections are: first, that we are mortal and ‘we have no stable dwelling on earth’ (Hb 13:14); secondly, that life does not end with death, because eternal life awaits us; thirdly, that we do not face the waves alone on the small boat of our planet because ‘the Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us.’ (Jn 1:14). The first of these three truths is the object of experience, the other two of faith and hope.

‘Memento mori!’

We shall start by meditating on the first of these ‘eternal maxims’: death. “Memento mori’, Remember you will die. The Trappist monks chose these words as the motto of their Order and they have it written everywhere in their cloisters.

You can talk about death in two different ways: either in the light of the kerygma or in the light of wisdom. The former consists in proclaiming that Christ has overcome death; that it is no longer a wall for everything to crash against, but it is a bridge to eternal life. The sapiential or existential way, on the other hand, consists in reflecting on the reality of death as it is accessible to human experience, to draw from it lessons to live a good life. It is in this perspective that we want to place the present meditation.

The existential way is the way death is approached in the Old Testament and in particular in the Wisdom books: ‘Teach us to count our days aright, that we may gain wisdom of heart,’ as the author of the Psalm asks God (Ps 90:12). This way of looking at death does not end with the Old Testament, but it also carries on in the Gospel of Christ. Let us remember his warning: ‘Stay awake, for you know neither the day nor the hour.’ (Mt 25:13), the conclusion of the parable of the rich man who planned to build larger barns for his harvest: ‘You fool, this night your life will be demanded of you; and the things you have prepared, to whom will they belong?’ (Lk 12:20), and again Jesus’ saying: ‘What profit would there be for one to gain the whole world and forfeit his life? Or what can one give in exchange for his life?’ (cf. Mt 16:26).

The tradition of the Church has made this teaching its own. The Desert Fathers treasured the thought of death so much that they made it a constant practice and refreshed it by any means necessary. One of them, who span wool for a living, had made it a habit of dropping the spindle every now and then and of ‘setting death before his eyes before picking it up again.’ In the Imitation of Christ we find the following exhortation: ‘In the morning assume you will not get to the evening. Once the evening has come, dare not rely on the following morning’ (I, 23). Saint Alphonsus Maria de Liguori wrote the treatise Preparation for Death, which for centuries was a classic of Catholic spirituality.

This sapiential way of talking about death can be found in every culture, not only in the Bible and in Christianity. Its secularized version is also present in modern thought and it is worth briefly touching on the conclusions drawn by two thinkers whose influence is still strong in our culture.

The first modern thinker in question is Jean-Paul Sartre. He overturned the classic relationship between essence and existence, claiming that existence precedes and prevails on essence. To put it simply, this means that there is no order or scale of objective values – God, the good, values, natural law, – which precede everything else and which humans have to live by, but everything has to start from one’s own individual existence and freedom. Every person must devise and fulfill their own fate, just as a river flows on and digs its own bed. Life’s plan is not written anywhere, but it is determined by one’s own choices.

Such a way of understanding existence completely ignores death as a fact and it is therefore disproven by the very reality of existence it wants to affirm. What can human beings plan if they do not know nor can they control whether they are still alive tomorrow? Sartre’s attempt resembles that of a convict who spends all his or her time planning the best route to follow to move from one wall of their cell to the other.

More plausible on this point is the thought of another philosopher, Martin Heidegger, who starts off from similar premises and works within the same context of existentialism. By defining man as ‘a-being-for-death,’ he does not turn death itself into an accident putting an end to life, but into the very substance of life, that is to say what it is made of. Man cannot live without burning life and making it shorter. Every minute that goes by is taken from life and handed on to death, just as, as we drive along, we see houses and trees quickly disappearing behind us. Living for death means that death is not only the end, as in the conclusion, but the end, as in the goal, of life. One is born to die, not for anything else.

What is, then, – the philosopher asks – that ‘hard core – certain and insurmountable,’ which human being are called to by their conscience and which is to act as the foundation of their existence, if it wants to be a ‘genuine’ one? The answer is: its nothingness! All human possibilities are actually ‘impossibilities.’ Any attempt to plan oneself and to raise oneself is a leap that starts from nothing and ends into nothing .All we can do is turn necessity into a virtue by loving our Destiny. A modern version of the Stoic ‘amor Fati’!

Saint Augustine had anticipated even this insight of modern thought on death, but he drew a totally different conclusion from it: not nihilism, but faith in eternal life.

When human beings are born – he wrote – many hypotheses are made: perhaps they will be beautiful, perhaps they will be ugly; perhaps they will be rich, perhaps they will be poor; perhaps they will live long, perhaps they will not. But of no one it is said: perhaps they will die or perhaps they will not die. This is the only thing that is absolutely certain about life. When one suffers from dropsy [this was the incurable disease at the time, nowadays others are], we say: ‘Poor thing, he or she has to die; they are doomed, there is no remedy.’ But should we not say the same of those who are born? “Poor thing, she has to die, there is no remedy, she is doomed!”. What difference does it make if it takes longer or shorter? Death is a mortal illness we are infected by when we are born.

Dante Alighieri summed up the whole of this Augustinian view in a single verse, as he defined human life on earth as ‘the life that is a race to death.’

At the school of ‘Sister Death’

With the quick advancement of technology and of scientific achievements, we ran the risk of being like that man in the parable, who says to himself: ‘Now as for you, you have so many good things stored up for many years, rest, eat, drink, be merry!’ (Lk 12:19). The current calamity has come to remind us how little depends on human will when it comes to ‘planning’ and determining the future.

A sapiential view of death preserves, after Christ, the same role played by the law after the coming of grace. It too is used to guard love and grace. The law – as it is written – was given for sinners (cf. 1Tm 1:9) and we are still sinners, that is to say subject to the lure of the world and of visible things, always tempted to ‘conform ourselves to this age’ (cf. Rm 12:2). There is no better vantage point to see the world, to see ourselves and all events, in their very truth, than that of death. Everything then takes its right place.

The world often appears as an inextricable bundle of injustice and chaos, to such an extent that everything seems to happen at random without there being any consistency or plan. A sort of shapeless painting, in which all the elements and colours seem to be placed randomly, just as in certain modern paintings. You often witness the triumph of iniquity while innocence is punished. However, to avert the belief that there is anything fixed and constant in the world, Bossuet observed that sometimes you see the opposite: innocence on the throne and injustice on the gallows!

Is there a vantage point from which to look at this huge picture and grasp its meaning? Yes, there is: it is the “end”, that is death, immediately followed by the judgment of God (cf. Hb 9:27). Seen from there, everything gets its right value. Death is the end of all differences and forms of injustice that exist amongst men. Death, as the Italian comedian Totò used to say, is like a ‘bubble level,’ capable of leveling out all privileges.

Looking at life from the vantage point of death is of extraordinary help to live well. Are you anguished by problems and difficulties? Walk ahead, set yourself in the right place: look at these things from your deathbed. How would you like to have behaved? How important would you hold these things to be? Have you got any issue with someone? Look at things from your deathbed. What would you like to have done then: to have won or to have accepted humiliation? To have prevailed or forgiven?

The thought of death prevents us from getting attached to things, or from setting our hearts on our earthly dwelling, forgetting that ‘we have no lasting city’ on earth (Hb 13:14). As a Psalm says, ‘at his death [a man] will not take along anything, his glory will not go down after him’ (Ps 49:18). In Antiquity, kings used to be buried with their jewels. This of course encouraged the practice of violating tombs to steal those treasures. Many such tombs have been found where, to keep violators away, an inscription on the tomb itself said: ‘There is only me here.’ That inscription was so true, even if, in fact, the tomb did hide those jewels! “At his death a man will not take along anything”.

‘Keep watch!’

Sister Death really is a good elder sister and a good teacher. It teaches us many things. if only we can listen gently. The Church is not afraid of sending us to her school. In the liturgy of Ash Wednesday there is an antiphon that sounds strong, even stronger in its original Latin words: Emendemus in melius quae ignoranter peccavimus; ne subito praeoccupati die mortis, quaeramus spatium poenitentiae, et invenire non possimus. ‘Should the day of death suddenly overtake us, let us amend what we have transgressed through ignorance, lest we seek the time of repentance and cannot find it’. One day, one sole hour, a good confession: how would these things look different at that time! How would we rather have those than a long life, full of riches and health!

I am also thinking of another context beyond the ascetic sphere in which we urgently need sister death as a teacher: evangelization. The thought of death is almost the only weapon left to shake drowsiness off our opulent society, experiencing exactly the same as the Israelites freed from Egypt: ‘So Jacob ate and was satisfied, Jeshurun grew fat and kicked…They forsook the God who made them and scorned the Rock of their salvation’ (Dt 32:15).

At a delicate point in the history of the “chosen people” God said to the prophet Isaiah: ‘Proclaim!’ ‘Proclaim!’. The prophet answered: ‘What shall I proclaim?’ and God said “All flesh is grass, and all their loyalty like the flower of the field. The grass withers, the flower wilts, when the breath of the Lord blows upon it”’ (Is 40: 6-7). I believe that God is giving the same instruction to his prophets today and he is doing so because he loves his children and does not want that ‘like a herd of sheep they will be put into Sheol, and death will shepherd them’ (cf. Ps 49:15).

The question about the meaning of death played a remarkable role in the early evangelization of Europe and we should not rule out that it may play a similar one in the current effort to re-evangelize it. There is indeed something that has not changed at all since then and it is precisely this: humans are to die. The Venerable Bede recounts how Christianity entered northern England, by overcoming the resistance of paganism. The king summoned the great assembly of his kingdom to decide on the issue whether to allow Christian missionaries in or not. There were opposing views on this, when one of his officials put it this way:

Human life on earth, o king, may be described as follows. Imagine it is winter. You are sitting at dinner with your dukes and your assistants. At the centre of the hall there is a fire heating up the room, while outside a storm of rain and snow is raging. A sparrow suddenly arrives at your palace; it comes in from an open window and very quickly leaves from the opposite side. Until it is inside, it is sheltered from the cold of winter, but a moment later, behold, it is cast back into the darkness it came from and it disappears out of sight. Our life is just like that! We do not know what comes before, or after, it. If this teaching can tell us something more certain on it, I think we should listen to it.

It was the question put by death itself that paved the way to the Good News, as an open wound in the human heart. A well-known psychologist has written against Freud that refusal of death, not sexual instinct, is at the root of every human action.

Praised be You, my Lord, through our Sister Bodily Death

In that way, we are not restoring the fear of death. Jesus came ‘to free those who, through fear of death had been subject to slavery all their life’ (Hb 2:15). He came to free us from the fear of death, not to increase it. However, one needs to have experienced that fear to be freed from it. Jesus came to teach the fear of eternal death to those who knew none other than the fear of bodily death.

Eternal death! In the Book of Revelation or Apocalypse it is called ‘the second death’ (Rev 20:6). It is the only one that really deserves the name of death, because it is not a passage, the Pascal mystery of Easter, but a terrible terminal. It is to save men and women from this tragic destiny that we have to go back to preaching about death. No-one more than Francis of Assisi has ever known the new Paschal face of Christian death. His own death was really a Paschal transition, a “transitus”, as it is celebrated in the Franciscan liturgy. As he was feeling close to death, the Little Poor once cried out: ‘Welcome, my sister death!’

Yet in his Canticle of the Sun or of the Creatures, along those very sweet words about death, he has some of the most frightening ones:

Praised be you, my Lord, through our Sister Bodily Death

From whom no living being can escape:

How dreadful for those who die in mortal sin!

How blessed are those she finds in your most holy will

For the second death can do them no harm.

How dreadful for those who die in mortal sin! ‘The sting of death is sin’, the Apostle says (1Cor 15:56). What gives death its most fearsome power of haunting a believing person and of frightening him or her is sin. If one lives in mortal sin, death still has its sting, its poison, just like before Christ, and therefore it wounds, kills and throws into the Gehenna. Do not be afraid – Jesus tells us – of the death that kills the body and then can do nothing more. Be afraid of the death which, after killing the body, has the power of throwing into the Gehenna (cf. Lk 12:4-5). Take sin away and you will also have taken its worst sting away from death!

With the institution of the Eucharist Jesus preempted his own death. We can do the same. In fact, Jesus invented this means to make us take part in his death, to unite us to himself. Taking part in the Eucharist is the most genuine, accurate and efficient way of ‘preparing’ for death, in St Alphonse de Liguori’s terms. In it we also celebrate our own death, and we offer it up, day by day, to the Father. In the Eucharist we can raise to the Father our ‘amen’, our ‘yes,’ to what awaits us, to the kind of death he will want to permit for us. In it we write “our will”: we decide to whom we want to leave our life, for whom we want to die.

We were born, it is true, to be able to die; death is not only the end, as in the conclusion, but also the end, as in the goal, of life. This, though, far from looking like a condemnation, as claimed by the above-mentioned philosopher, on the contrary appears to be a privilege. ‘Christ – as St Gregory of Nyssa put it – was born to be able to die,’ that is to be able to give his life as a ransom for all. We too have received life to have something unique, valuable, worthy of God, to be able to give him back in turn as a gift and as a sacrifice. What greater use can one think of making of life, than giving it, out of love, to the Creator who, out of love, gave it to us? Adapting the words of consecration uttered by the celebrant over the bread and wine at Mass we can say: ‘Through your goodness we have this our life to offer; we bring it to you. May it become a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to you’ (cf. Rm 12:1).

With all this we have not taken away its sting from the thought of death and its capacity to anguish us that Jesus also wanted to experience in Gethsemane. We are at least more ready to accept the assurance that comes from faith and that we proclaim in the preface of the Mass for the dead:

For your faithful, Lord,

life is changed not ended,

and, when this earthly dwelling turns to dust,

an eternal dwelling is made ready for them in heaven.

God willing, we shall speak of this eternal dwelling in heaven, in the next meditation.

________________________________________

Translated from Italian by Paolo Zanna.

1. Biblical quotations are taken from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops Bible.

2. Homilies on the Gospel, XVII.

3. Apofthegms of ms. Coislin 126, n. 58.

4. Cf. M. Heidegger, Being and Time, § 51.

5. Ib. II, c. 2, § 58.

6. Cf. St Augustine, Sermo Guelf. 12, 3..

7. Purgatorio, XXXIII, 54 (Mandelbaum’s English translation, 1982).

8. See Ecclesiastical History, II,13.

9. E. Becker, Denial of Death, New York: Free Press. 1973.

10. Celano, Vita secunda , CLXIII, 217.

11. St Gregory of Nyssa, Or. cat., 32 (PG 45, 80).