Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

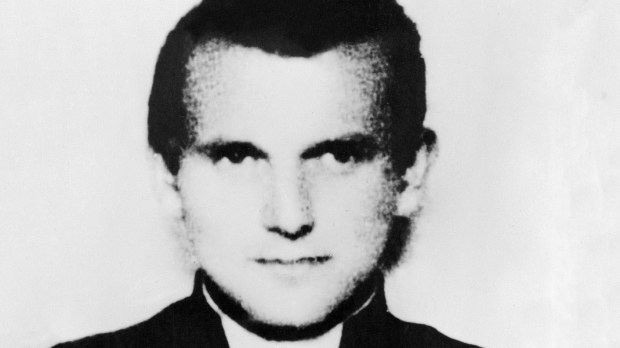

A Canadian priest who spends much of his time doing research at the Vatican has uncovered what he believes to be the first mention of future Pope John Paul II in a letter to the Vatican.

The letter dates from 1946, when Karol Wojtyla was about to become a priest. It was discovered in September by Fr. Athanasius D. McVay, a priest of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church who for more than 20 years has been doing research in Vatican archives regarding Ukraine. The letter he found is in the Archive of the Second Section of the Secretariat of State. Together with all the 1939–1958 materials, it had been under embargo until March of this year.

“I was going through reports from 1942 on German-occupied Poland, when I discovered the letter,” Fr. McVay told Aleteia.

The document is from the Archbishop of Krakow, Adam Sapieha, who fought for the rights of the Roman Catholic Church in Poland during Nazi occupation from 1939-1945. German authorities “slated his Church and his people for destruction,” Fr. McVay wrote in a post at his blog, Annales Ecclesiae Ucrainae.

Fr. McVay, who is originally from Winnipeg, Manitoba, is a fellow of the Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto. His books include God’s Martyr, History’s Witness: Blessed Nykyta Budka: First Ukrainian Catholic Bishop of Canada.

He noted that Adolf Hitler had plans for the Slavic peoples that were similar to his plans for the Jews. And the Church was far from immune.

“While the Catholic Church was barely tolerated in western Europe, in the east it was being destroyed,” Fr. McVay writes. “Polish bishops, clergy, and religious were imprisoned and killed, seminaries and universities were shut. Church leaders had to find creative ways to provide ministry to their suffering flocks.”

Sapieha was not cowed. He “demonstrated fearless strength in dealing with the occupiers,” McVay writes at his blog. The archbishop appealed directly to the governor of German-occupied Poland, condemning the killings, arrests, and restrictions on ministry, and asking that seminaries be allowed to reopen. But even with the intervention of Pope Pius XII, Sapieha got nowhere.

Because priests were being imprisoned and murdered, Sapieha opened a clandestine seminary. Karol Wojtyla joined it in 1942.

When the archbishop informed Rome about the underground seminary, Pius XII sent a message of support, calling the initiative “so important for the future of the Church in those regions.”

“Little did the pontiff know how important the underground seminary would become for the entire world,” McVay notes. “It was already preparing his successor in the Chair of Peter.”

With the end of the war and the Nazi defeat, Poland came under a Soviet-backed communist regime. But Sapieha “began to prepare the Polish Church to bring forth new laborers for the spiritual harvest,” McVay writes. Part of that was to get his seminarians a good education. Two in particular he wanted to send to Rome, but they needed diplomatic help in order to get out of communist Poland. On September 22, 1946, while Wojtyla was still a lay seminarian, his bishop sent a letter to Msgr. Domenico Tardini, head of the Secretariat of State’s section for Extraordinary (Diplomatic) Affairs. This is the letter McVay found, written in Italian, and he reprints his translation of it at his blog:

Most Illustrious Monsignor,You will easily understand that we very much want to send our seminarians to Roman universities in order to give them the possibility to perfect their studies and to live, for a time, in the capital of the Church. However, in order to enter Italy, it is necessary to have permission from the Italian Government and to be provided for financially. Wherefore, I am asking if, in some way, You could obtain this permission for us. As to being looked after, they would stay at a College that would provide for them. For the moment, we hope to be able to obtain passport for two students, that is, Karol Wojtyła and Stanisław Starowiejski, students of Kraków Diocesan Seminary. I apologize, Monsignor, for disturbing You, but it was necessary to take advantage of the occasion.

Sapieha’s letter, which was accompanied by the two seminarians’ curricula vitae, arrived at the Vatican on October 1. A Vatican official was “at a loss to explain how it had been delivered,” McVay observes. “On 4 October, Tardini presented a nota verbale to the Italian Ambassador to the Holy See, asking for his assistance and mentioning the names of the two students.”

Wojtyla was ordained a priest on November 1 and arrived in Rome on November 15. He registered at the Pontifical Athenaeum (later University) of St. Thomas Aquinas (known as the Angelicum) on November 26. He went on to earn a doctorate in philosophy in 1948. The Angelicum still has the original copy of his typewritten thesis on “The Doctrine of Faith in St. John of the Cross.”

Fr. Wojtyla returned to Poland, where, like the bishop who ordained him, he would fight to defend the rights of the Church under a totalitarian regime.

The newly discovered letter sheds a little bit of light on a key move in Wojtyla’s early life.

“For a seminarian to be ‘mentioned in dispatches’ by name is a rare thing,” McVay notes. “And this letter might well represent the first mention of Wojtyła in correspondence with the Apostolic See, contained in Vatican archival collections.”

Update, October 28:It has come to Aleteia’s attention that a book by Johan Ickx, director of the Archive of the Second Section of the Secretariat of State, Le Bureau: Les Juifs de Pie XII, published September 24, also mentions the correspondence pertaining to Wojtyła. Ickx reproduces a scan of the typed curriculum vitae sent to Rome but does not reproduce the text of Sapieha’s letter, nor mention some of the other details regarding the incident. Fr. McVay discovered the letter in September and blogged about it on September 20.