The magic word for the internet age is “content.” Whether you’re a podcast, a website, or a popular Twitter account, the key to grabbing attention and garnering clicks is to churn out new material at warp speed. The hot take is favored over the circumspect reflection, and the whole conversation moves to the next course before we’ve had the chance to digest.

Couple this with the fact that “the internet is forever,” as the ominous warning says. Every post we make on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and the like is stored in the mysterious “cloud,” in some archived version of webpage, ready to be retrieved at the proper time (to say nothing of the practice of screenshotting deleted material).

Since we know our takes will be spread about virally and recorded forever, we’re keen to stick by them no matter what—they’re part of our “brand,” after all; we can’t go back on them.

We’ve created a society where our most fleeting and intemperate thoughts are recorded and etched in stone (or silicon, as the case may be). Today’s saint gives us an exemplar of a more dispassionate, humble approach to communication.

Read more:

What a child taught St. Augustine at the seashore

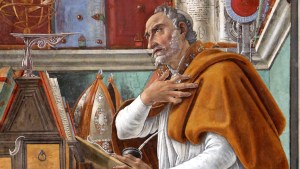

St. Augustine of Hippo, in addition to being one of the great saints, Fathers, and Doctors of the Church, was also one of its most voluminous writers. St. Augustine’s letters, commentaries, and treatises fill several shelves when printed and bound. (In fact, according to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “Augustine’s literary output surpasses the preserved work of almost all other ancient writers in quantity.”) One might think that, after producing such a great girth of material, the Doctor of Grace would have been content to let his writings speak for themselves. Yet instead, near the end of his life, St. Augustine reconsidered some of his positions.

A few years before his death, the venerable bishop of Hippo Regius published his Retractationes (“Reconsiderations”), a collection of reflections on his life’s works. The purpose of the text was “to gather together and point out, in a work devoted to this express purpose, all the things which most justly displease me in my books” and to “take a censor’s pen” to them.

To be clear: while an English speaker may be tempted to render the title as “retractions,” nowhere does St. Augustine reject any of his former positions. Instead, he uses the book to clarify, expound, and in some cases, restate what he was trying to say.

Retractationes consists of a list of St. Augustine’s works, and, as the scholar James J. O’Donnell writes, “for every work listed, he says something of the circumstances of composition and publication and adds something of the corrections and amendments that, in his old age, he found necessary.”

Many areas that received his attention were connected to his disputes with the Pelagians, who believed that grace was unnecessary for salvation, only Christ’s good example. Thus we see St. Augustine refine his thoughts on subjects including free will, grace, predestination, original sin, and merit. He also amends some of his commentaries on Scripture, noting that he had come to understand the Bible better in his old age.

Read more:

The Church’s own “wisdom from grandpa” is worth memorizing

It seems our era is heavy on defensiveness and short on humility. So often people brush off critiques and double-down on even their worst positions in a desperate attempt to maintain their pride. Here, St. Augustine, already renowned in his own day as one of the great minds of the age, acknowledges that his words were at times imprecise, intemperate, or ill-advised. Not only that, but he took the time to work through his texts systematically and address anything he felt merited it.

Are we less prone to error than the great Augustine? Are our own words and actions above reproach? Are we so concerned about how we are perceived that we’ve forgotten one of the most admirable characteristics is humility? That it’s the truth that sets us free?

We try to grip ourselves, or rather our image, so tightly that it shatters in our hands. It is only when we let go, when we care little enough about our image that we can say, “I’m sorry, I was wrong, I shouldn’t have said that,” that we can truly be free, truly be ourselves. True humility is the stuff of sanctity. Perhaps if we were more humble online, the internet, the world, would be a better place. Let us pray to St. Augustine that we might follow his example.

Read more:

Being dust that is loved … Reflecting with Pope Francis and Augustine