The Archdiocese for the Military Services has been called “the biggest diocese with the fewest priests,” as the number of Catholics serving in the military far outstrips the proportion of Catholic chaplains. Yet this “diocese without borders” does vital work in ministering to Catholic military personnel and their families. As their website explains,

The work of chaplains is not confined to the chapel. They go wherever their people are—in a tent in the desert, on the deck of an aircraft carrier, in the barracks on base, in a combat zone, in the halls of the Pentagon. Military service requires extraordinary sacrifices of those who serve and their families. Chaplains provide pastoral care through guidance, education, direction on Church doctrine, and spiritual counsel. Through their words and actions, they provide comfort and strength through the Word of God and the sacraments to those who serve to protect our Nation.

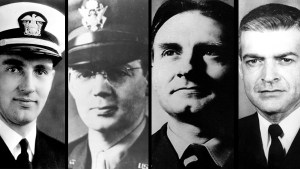

Serving as a military chaplain is a noble calling, but can be challenging work even in the best of times. Yet even in facing the worst of times, a number of military chaplains have shown extraordinary courage and strength of character—so much so that nine chaplains have been awarded the Medal of Honor over the decades. This medal is the nation’s highest and most prestigious military decoration for valor. Of those nine heroic chaplains, these five were Catholic priests.

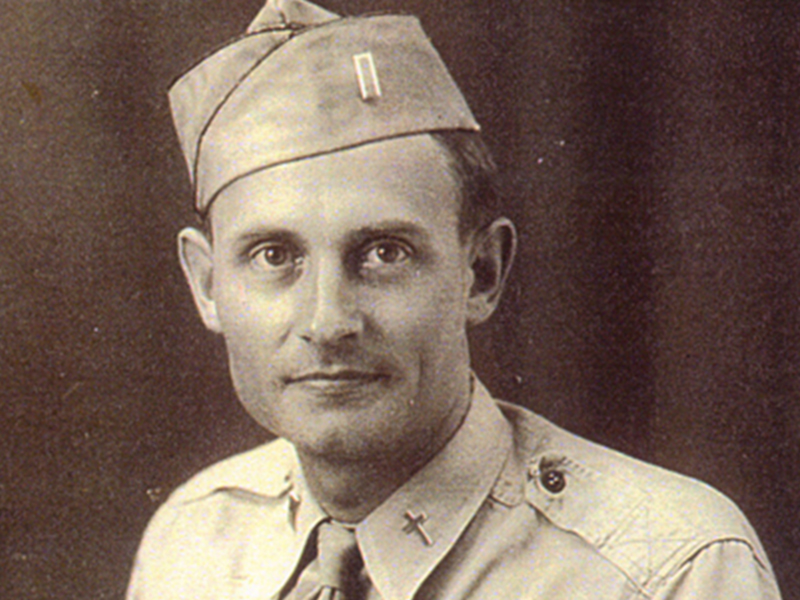

1Lt. Cmdr Joseph Timothy O’Callahan

Father O’Callahan was a Jesuit priest who served as a United States Navy chaplain during World War II, and was both the first Catholic priest and the first naval chaplain to earn the Medal of Honor. Before the war, he worked as a college professor, teaching philosophy and mathematics at Boston College and College of the Holy Cross. When World War II began, O’Callahan was 36 and nearsighted, with a bad case of claustrophobia and high blood pressure—an unlikely candidate for military service, much less for heroic valor. But faith can give a man courage and perseverance beyond human understanding, so in 1940 he left the quiet halls and libraries of academic life for a bold new adventure in the Chaplain Corps of the U.S. Navy Reserve.

He would soon see more adventure than he could have imagined. O’Callahan was serving as chaplain on the USS Franklin in March of 1945 when an enemy aircraft dropped two bombs that badly damaged the ship. His Medal of Honor citation reads,

A valiant and forceful leader, calmly braving the perilous barriers of flame and twisted metal to aid his men and his ship, Lieutenant Commander O’Callahan groped his way through smoke-filled corridors to the open flight deck and into the midst of violently exploding bombs, shells, rockets, and other armament. With the ship rocked by incessant explosions, with debris and fragments raining down and fires raging in ever-increasing fury, he ministered to the wounded and dying, comforting and encouraging men of all faiths; he organized and led firefighting crews into the blazing inferno on the flight deck; he directed the jettisoning of live ammunition and the flooding of the magazine; he manned a hose to cool hot, armed bombs rolling dangerously on the listing deck, continuing his efforts, despite searing, suffocating smoke which forced men to fall back gasping and imperiled others who replaced them. Serving with courage, fortitude, and deep spiritual strength, Lieutenant Commander O’Callahan inspired the gallant officers and men of the FRANKLIN to fight heroically and with profound faith in the face of almost certain death and to return their stricken ship to port.

While leading the men through this inferno, he gave the Sacrament of Last Rites to the men dying around him, all while battling his claustrophobia. Against all odds, the USS Franklin made it back to the Brooklyn Navy Ship Yard, in large part thanks to Father O’Callahan’s quick thinking and fearless leadership in a crisis.

A few months later, when awards were presented on the battered flight deck of the USS Franklin, O’Callahan’s mother came aboard the ship, and The New England Historical Society reports this telling conversation:

The ship’s captain, Les Gehres, went over to his mother and said, “I’m not a religious man. But I watched your son that day and I thought if faith can do this for man, there must be something to it. Your son is the bravest man I have ever seen.”

Read more:

This WWI chaplain risked his life to save the souls of his soldiers

2Captain Emil J. Kapaun

Father Kapaun grew up on a farm in Kansas, the son of Czech immigrants. He was ordained in 1940 and served as a pastor at the parish where he grew up until 1944, when his bishop relented to his request of becoming a U.S. Army chaplain. He first served in the Burma Theater of World War II, then some years later, he was sent to Japan in 1949 to minister during the Korean War.

During the Battle of Unsan, Kapaun was serving with the 3rd Battalion of the 8th Cavalry Regiment when he was taken prisoner:

As Chinese Communist forces encircled the battalion, Kapaun moved fearlessly from foxhole to foxhole under direct enemy fire in order to provide comfort and reassurance to the outnumbered Soldiers. He repeatedly exposed himself to enemy fire to recover wounded men, dragging them to safety. When he couldn’t drag them, he dug shallow trenches to shield them from enemy fire. As Chinese forces closed in, Kapaun rejected several chances to escape, instead volunteering to stay behind and care for the wounded. He was taken as a prisoner of war by Chinese forces on Nov. 2, 1950.

“Father Kapaun had several chances to get out, but he wouldn’t take them,” Warrant Officer John Funston later recounted. After his capture at Unsan, Father Kapaun and the wounded men with him joined hundreds of other American prisoners on a forced march to a POW camp near Pyoktong.

The men suffered severe injuries and bitter cold; dozens fell behind and were left to freeze to death along the way. But throughout this torture, Father Kapaun did not lose his compassion and concern for his men: The BBC reports that “Survivors said that Kapaun, even as he was suffering frostbite on his feet, helped carry wounded men in litters hundreds of miles, shaming recalcitrant comrades into helping.”

When they reached the camp, the men were left freezing and near starving, with pitifully meager food and shelter. Kapaun sneaked around the camp stealing food from the Chinese stores, and even fed others from his own rations. He tended the sick and wounded, bathing them, washing their clothes, and picking off lice, all while ignoring his own ill health. When the prisoners were forced to endure indoctrination sessions, he patiently and politely rejected every false theory that the instructors presented. He even managed to lead a sunrise service on Easter. A survivor of the camp, Captain Robert Burke, later wrote,

“By February and March, the majority of us had turned into animals, were fighting for food, irritable, selfish, miserly. The good priest continued to keep a cool head, conduct himself as a human being, and maintain all his virtues and ideal characteristics. When the chips were down, Father proved himself to be the greatest example of manhood I’ve ever seen in my life.”

As Father Kapaun’s health grew worse, his captors took him to the “hospital,” a place in the camp where he was left to die of malnutrition and pneumonia. Yet his indomitable spirit and faith in God persisted to the last. Another survivor of the camp, Felix McCool, recalled Father Kapaun’s last words:

“In his last hour he heard my confession. Father Kapaun said: ‘As you see, I am crying too, not tears of pain but tears of joy, because I’ll be with my God in a short time.'”

The Diocese of Wichita is promoting his cause for canonization, and in 1993 St. John Paul II declared him a Servant of God.

Read more:

4 Heroic military chaplains who died in battle

3Major Charles Joseph Watters

Born and raised in New Jersey, Father Watters was ordained in 1953 and served in the Archdiocese of Newark until entering active duty as a U.S. Army chaplain in 1964. He served a 12-month tour of duty in Vietnam from July 1966 to July 1967, during which he was awarded the Air Medal and a Bronze Star for Valor. At the end of this time, he voluntarily extended his tour for another six months. It was during these additional months that he made the ultimate sacrifice. Part of his Medal of Honor citation describes the events of November 19, 1967:

Chaplain Watters was moving with one of the companies when it engaged a heavily armed enemy battalion. As the battle raged and the casualties mounted, Chaplain Watters, with complete disregard for his safety, rushed forward to the line of contact. Unarmed and completely exposed, he moved among, as well as in front of the advancing troops, giving aid to the wounded, assisting in their evacuation, giving words of encouragement, and administering the last rites to the dying. When a wounded paratrooper was standing in shock in front of the assaulting forces, Chaplain Watters ran forward, picked the man up on his shoulders and carried him to safety. As the troopers battled to the first enemy entrenchment, Chaplain Watters ran through the intense enemy fire to the front of the entrenchment to aid a fallen comrade. A short time later, the paratroopers pulled back in preparation for a second assault. Chaplain Watters exposed himself to both friendly and enemy fire between the two forces in order to recover two wounded soldiers. Later, when the battalion was forced to pull back into a perimeter, Chaplain Watters noticed that several wounded soldiers were lying outside the newly formed perimeter. Without hesitation and ignoring attempts to restrain him, Chaplain Watters left the perimeter three times in the face of small arms, automatic weapons, and mortar fire to carry and to assist the injured troopers to safety. Satisfied that all of the wounded were inside the perimeter, he began aiding the medics — applying field bandages to open wounds, obtaining and serving food and water, giving spiritual and mental strength and comfort. During his ministering, he moved out to the perimeter from position to position redistributing food and water, and tending to the needs of his men. Chaplain Watters was giving aid to the wounded when he himself was mortally wounded.

4Lt. Vincent Robert Capodanno

Father Capodanno was the youngest of ten children born to Italian immigrants in New York, but he learned to grapple with hardship and suffering at a young age when his father died suddenly on his 10th birthday. He felt called to the priesthood from a young age, and after nine years of intense preparation, he was ordained a Maryknoll Missioner priest in 1958. His first assignment was in Taiwan, where he ministered to the Hakka-Chinese while working to learn and understand their language.

After 6 years of service there, he was on leave in the United States when he was assigned to a new mission in Hong Kong. But he felt drawn to service as a military chaplain, especially as three of his brothers had served in World War II when he was a child. He asked his superiors for permission to join the Navy Chaplain Corps, wanting to serve the increasing number of Marine troops in Vietnam. In December 1965, Father Capodanno received his commission as a lieutenant in the Navy Chaplain Corps, and in 1966 he reported to the 7th Marines in Vietnam.

Because of his focus on the young enlisted troops, or “grunts,” and his willingness to share in the same hardships as his men, Father Capodanno earned the nickname “the Grunt Padre.” As chaplain for the battalion, his ministry involved not just administering the sacraments, but also caring for the troops’ every spiritual need. His biography says,

He became a constant companion to the Marines: living, eating, and sleeping in the same conditions of the men. He established libraries, gathered and distributed gifts and organized outreach programs for the local villagers. He spent hours reassuring the weary and disillusioned, consoling the grieving, hearing confessions, instructing converts, and distributing St. Christopher medals. Such work “energized” him, and he requested an extension to remain with the Marines.

It was during that second tour that Father Capodanno made the ultimate sacrifice. His Medal of Honor citation describes his heroic death:

In response to reports that the [platoon] was in danger of being overrun by a massed enemy assaulting force, Lt. Capodanno left the relative safety of the company command post and ran through an open area raked with fire, directly to the beleaguered platoon. Disregarding the intense enemy small-arms, automatic-weapons, and mortar fire, he moved about the battlefield administering last rites to the dying and giving medical aid to the wounded. When an exploding mortar round inflicted painful multiple wounds to his arms and legs, and severed a portion of his right hand, he steadfastly refused all medical aid. Instead, he directed the corpsmen to help their wounded comrades and, with calm vigor, continued to move about the battlefield as he provided encouragement by voice and example to the valiant marines. Upon encountering a wounded corpsman in the direct line of fire of an enemy machine gunner positioned approximately 15 yards away, Lt. Capodanno rushed a daring attempt to aid and assist the mortally wounded corpsman. At that instant, only inches from his goal, he was struck down by a burst of machine gun fire.

Later on, Marine Cpl. Ray Harton, who was wounded at that battle but survived, recalled seeing Father Capodanno just before he died. Capodanno calmly told him, “Stay quiet, Marine. You will be okay. Someone will be here to help you soon. God is with us all this day.”

Those may have been Father Capodanno’s last words. Surely God was with the holy priest that day, and one can imagine the greeting in Heaven: “Well done, good and faithful servant.” The Archdiocese for the Military Services is promoting his cause for canonization, and in 2006 he was declared a Servant of God.

5Captain Angelo J. Liteky

Captain Liteky was known later in life as Charles James Liteky, and his name was not the only thing that changed after he returned from the Vietnam War. Over the course of 20 years, he left the priesthood, married a former religious sister, became a peace activist, and returned his Medal of Honor to the government—the only recipient ever to renounce the Medal. Yet, in a way, his peace activism was not a philosophical rupture from his acts of valor during the Vietnam War; he was recognized not for any fighting he did, but for putting himself in danger to save the lives of 23 wounded men during an intense battle. His Medal of Honor citation describes his heroic actions:

He was participating in a search and destroy operation when [his company] came under intense fire from a battalion size enemy force. Momentarily stunned from the immediate encounter that ensued, the men hugged the ground for cover. Observing 2 wounded men, Chaplain Liteky moved to within 15 meters of an enemy machine gun position to reach them, placing himself between the enemy and the wounded men. When there was a brief respite in the fighting, he managed to drag them to the relative safety of the landing zone. Inspired by his courageous actions, the company rallied and began placing a heavy volume of fire upon the enemy’s positions. In a magnificent display of courage and leadership, Chaplain Liteky began moving upright through the enemy fire, administering last rites to the dying and evacuating the wounded. Noticing another trapped and seriously wounded man, Chaplain Liteky crawled to his aid. Realizing that the wounded man was too heavy to carry, he rolled on his back, placed the man on his chest and through sheer determination and fortitude crawled back to the landing zone using his elbows and heels to push himself along. Pausing for breath momentarily, he returned to the action and came upon a man entangled in the dense, thorny underbrush. Once more intense enemy fire was directed at him, but Chaplain Liteky stood his ground and calmly broke the vines and carried the man to the landing zone for evacuation. On several occasions when the landing zone was under small arms and rocket fire, Chaplain Liteky stood up in the face of hostile fire and personally directed the medivac helicopters into and out of the area. With the wounded safely evacuated, Chaplain Liteky returned to the perimeter, constantly encouraging and inspiring the men. Upon the unit’s relief on the morning of 7 December 1967, it was discovered that despite painful wounds in the neck and foot, Chaplain Liteky had personally carried over 20 men to the landing zone for evacuation during the savage fighting.

Read more:

Military chaplains served the ones who served

Read more:

D-Day, 74 years later: Remembering the heroic chaplains and priests of Normandy