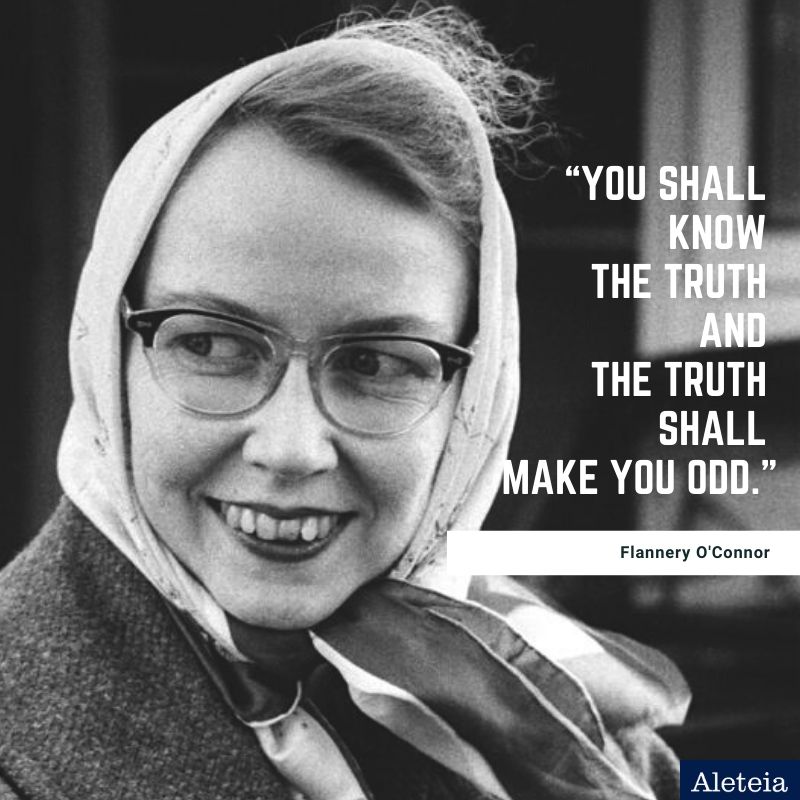

The tensions around race relations have flared in our country on the heels of the coronavirus pandemic, such that it’s hard to know where to turn one’s thoughts these days, a time that needs healing on both the physical level as well as the social and spiritual. A request from a friend for some new fiction to read spurred me to read with her the short stories of Flannery O’Connor, the Catholic author from Georgia, who entered the American literary scene in the late 1940s and now has a seemingly-permanent place in the canon of American literature alongside her fellow Southern regionalists Faulkner and Welty.

Almost all of O’Connor’s short stories include the relationship of whites and Blacks as a major element. Most often she plays on the prejudices of her place and time in ways that are jarring to a modern reader. Her frequent use of the n-word, the blatant classification by her protagonists of Blacks as inferior—or at least separate—are at times cringe-worthy and often makes you feel like you shouldn’t really be reading this. But universally, she shows these biases to be unjustly—sinfully, even—narrow-minded in a way that besmirches the character’s virtue, only to be cracked open, often literally, by a moment of violent grace. Only in this way can certain people be brought to conversion. As she writes in her essay “The Fiction Writer & His Country”:

The novelist with Christian concerns will find in modern life distortions which are repugnant to him, and his problem will be to make these appear as distortions to an audience which is used to seeing them as natural; and he may well be forced to take ever more violent means to get his vision across to this hostile audience. When you can assume that your audience holds the same beliefs you do, you can relax a little and use more normal ways of talking to it; when you have to assume that it does not, then you have to make your vision apparent by shock — to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost blind you draw large and startling figures(Mystery and Manners, 33-34).

Read more:

‘Good Things Out of Nazareth’: A look at the collection of Flannery O’Connor’s letters

That is, while Miss Flannery found herself in an American South where the social conventions dictated a whole set of prejudices, her Christian and Catholic faith pointed her elsewhere. This disparity touched her both as a writer and a Christian. Her place as a writer required her to make use of her time and place, which every writer has to do in some way, to point out the injustice of these prejudices. Her place as a Christian, however, required her to do so not in the name of “civil rights” or “social justice,” but in the name of Christ who came to save all people and effect a real union of all peoples with God, regardless of race.

Paul Elie, the author of the best book I’ve read on 20th-century American Catholic authors, The Life You Save May Be Your Own (a title borrowed from one of O’Connor’s short stories), has recently questioned whether O’Connor was in fact concerned enough throughout her life with “That Issue,” as she calls it in one of her letters. He shows through citations of early childhood journal entries and letters that she was firmly a part of her segregationist South’s culture in her references to Black people and her inability to see them as equal members of the human race. He concedes at one point that no one should be held accountable for “juvenilia,” but then goes on to cite later examples, even at the end of her life, where she displays a consistently bigoted stance toward Black people. (These passages have been interpreted by other commentators as an ironic parroting of the sort of discourse in the air of her time, but Elie is not convinced.) Despite his clear appreciation for O’Connor, and her ability to intertwine her art and her Faith, Elie ultimately casts her as just another Southerner who went North and got some Yankee values that didn’t quite permeate deep enough for the values at play in 2020.

Elie’s earlier book is subtitled An American Pilgrimage. He shows, through a masterful intertwining of the lives of Dorothy Day, Walker Percy, Thomas Merton, and Flannery O’Connor, how their Catholic faith led them each on a personal odyssey, sometimes intersecting with each other, through the many Scyllae and Charybdes of 20th-century life. A decade and a half later, in his most recent article on O’Connor—whom he seems to appreciate the most of the four—he laments that O’Connor’s pilgrimage didn’t go far enough on the issue of race relations. She’s another example from recent history of ingrained prejudice and an unwillingness to see the truth that “all men are created equal.”

Read more:

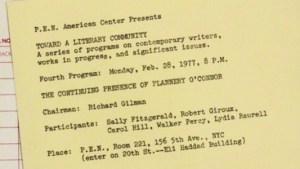

Previously unreleased: Hear Walker Percy and others discuss Flannery O’Connor

But before she was a writer, Mary Flannery O’Connor was first, and foremost, a Christian.That is, a fallen human being living in a fallen world full of people in need of redemption and continual conversion. She knew that—the writer can’t help but write what he or she knows personally—and we can see through her craft how she allowed the grace of Christ to break in not just through violent sprays in the lives of her hapless characters, but, we should presume, in her own life as well. We should take O’Connor at her word, her many words, where she shows the blindness of racism, and that what makes a person better or worse is not their skin color or economic situation, but their ability to allow the grace of God to permeate their life and join the great dance to heaven she describes in Mrs. Turpin’s vision in the late story “Revelation,” to take only one example:

…. a vast horde of souls were rumbling toward heaven. There were whole companies of white-trash, clean for the first time in their lives, and bands of black n—–s in white robes, and battalions of freaks and lunatics shouting and clapping and leaping like frogs. And bringing up the end of the procession was a tribe of people whom she recognized at once as those who, like herself and Claud, had always had a little of everything and the God-given wit to use it right. . . . They were marching behind the others with great dignity, accountable as they had always been for good order and common sense and respectable behavior. Yet she could see by their shocked and altered faces that even their virtues were being burned away. (Collected Short Stories, 508).

Elie detects in in this final pilgrimage the unfortunately unconverted, still-segregated vision of Milledgeville, Georgia’s most famous writer. The pilgrimage Elie highlights is at once the same for everybody and endlessly unique to each Christian. That pilgrimage is not toward some vague sense of peace and unity according to the most recent set of values and requirements, but toward the ancient procession of the saints to Heaven, in whatever order God ordains. Can we doubt that Flannery O’Connor would have admitted, even as she lay dying of the effects of lupus in her hospital bed in 1964, that she was still in need of on-going conversion and repentance, that she was in need of the burning fire of God’s love to purify her, to heal her, and make her whole? Can any of us really ask for anything more?

Make sure to visit the slideshow below to discover four insightful phrases from Flannery O’Connor on how to become your better possible self.