Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

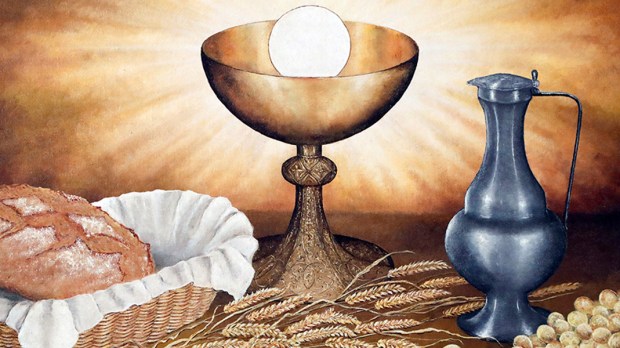

At the Last Supper Jesus instituted the Eucharist, using the elements of bread and wine in the context of the Passover meal.

While they were eating, Jesus took bread, said the blessing, broke it, and giving it to his disciples said, “Take and eat; this is my body.” Then he took a cup, gave thanks, and gave it to them, saying, “Drink from it, all of you, for this is my blood of the covenant, which will be shed on behalf of many for the forgiveness of sins. (Matthew 26:26-28)

The Catechism of the Catholic Churchexplains, “This [Jesus] did in order to perpetuate the sacrifice of the cross throughout the ages until he should come again, and so to entrust to his beloved Spouse, the Church, a memorial of his death and resurrection: a sacrament of love, a sign of unity, a bond of charity, a Paschal banquet ‘in which Christ is consumed, the mind is filled with grace, and a pledge of future glory is given to us‘” (CCC 1323).

However, the question is often asked, “Why bread and wine? Couldn’t Jesus have used something else?”

It is true, Jesus, being God, could have established his enduring presence in the Church through anything in his creation. He could have used other types of food, such as lettuce, figs, apricots or even meat.

Yet, God chose bread and wine.

The primary reason why God chose bread and wine was connected to his previous revelations in the Old Testament and how he was preparing his people for this moment in history.

In the Old Covenant bread and wine were offered in sacrifice among the first fruits of the earth as a sign of grateful acknowledgment to the Creator. But they also received a new significance in the context of the Exodus: the unleavened bread that Israel eats every year at Passover commemorates the haste of the departure that liberated them from Egypt; the remembrance of the manna in the desert will always recall to Israel that it lives by the bread of the Word of God; their daily bread is the fruit of the promised land, the pledge of God’s faithfulness to his promises. The “cup of blessing” at the end of the Jewish Passover meal adds to the festive joy of wine an eschatological dimension: the messianic expectation of the rebuilding of Jerusalem. When Jesus instituted the Eucharist, he gave a new and definitive meaning to the blessing of the bread and the cup. (CCC 1334)

God always knew he would use bread and wine, so he began preparing the people of Israel for this revelations gradually over time. The Old Testament is full of symbolic precursors, making Jesus’ actions at the Last Supper a very fitting fulfillment of what had already taken place.

Besides the connections to various events in salvation history, God likely used bread and wine because of its rich symbolism in how they are made.

For example, St. Augustine in his sermon Ad infantes, de Sacramentis lays out the symbolism of the manufacturing of bread and how it expresses the “communion” we are called to celebrate.

In this loaf of bread you are given clearly to understand how much you should love unity. I mean, was that loaf made from one grain? Weren’t there many grains of wheat? But before they came into the loaf they were all separate; they were joined together by means of water after a certain amount of pounding and crushing. Unless wheat is ground, after all, and moistened with water, it can’t possibly get into this shape which is called bread. In the same way you too were being ground and pounded, as it were, by the humiliation of fasting and the sacrament of exorcism. Then came baptism, and you were, in a manner of speaking, moistened with water in order to be shaped into bread. But it’s not yet bread without fire to bake it. So what does fire represent? That’s the chrism, the anointing. Oil, the fire-feeder, you see, is the sacrament of the Holy Spirit … You see, he breathes into us the charity which should set us on fire for God, and have us think lightly of the world, and burn up our straw, and purge and refine our hearts like gold. So the Holy Spirit comes, fire after water, and you are baked into the bread which is the body of Christ. And that’s how unity is signified.

This is confirmed in St. Paul’s letter to the Corinthians, “Because the loaf of bread is one, we, though many, are one body, for we all partake of the one loaf” (1 Corinthians 10:17).

Bread has also been a staple food in various cultures around the world, something universal that everyone can understand.

Wine has a similar symbolism, again stressing the way it is manufactured. St. Augustine summarizes the symbolism in another sermon.

But just as one loaf is made from single grains collected together and somehow mixed in with each other into dough, so in the same way the body of Christ is made one by the harmony of charity. And what grains are for the body of Christ, grapes are for his blood; because wine too comes out from the press, and what was separated one by one in many grapes flows together into a unity, and becomes wine. Thus both in the bread and in the cup there is the mystery, the sacrament, of unity. (Sermon 229A)

This is only a small sample of the symbolism found in bread and wine that the Catholic Church has been able to reflect on for many centuries.

Read more:

4 Incredible Eucharistic miracles that defy scientific explanation

Read more:

What was Mass like for the early Christians?