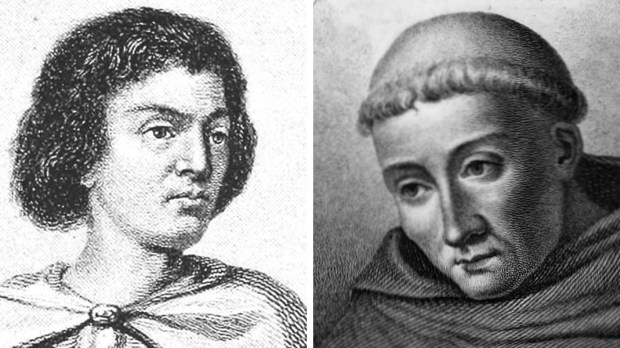

Peter Abelard and St. Bernard of Clairvaux were two of the most influential theologians of the medieval age, and their stories intersected in a way that forever will link them prominently in Catholic history books.

More precisely, that history likely regards them as enemies, University of Chicago professor Dr. Willemien Otten said recently in a webinar lecture.

And yet …

“I’m calling this (lecture) ‘Theologians at Cross Purposes,’” the professor said near the beginning of her presentation. Otten chose to observe the two 12th-century theologians not purely through the lens of their differences and verbal skirmishes but rather for the things they had in common.

“That’s more useful than calling them enemies,” she said, as they both advocated “a kind of reform of monastic life and how to think and talk about Tradition” in the Church.

Otten is a professor of Theology and the History of Christianity in the University of Chicago’s Divinity School as well as an associate faculty member in the university’s history department. Her live-streamed lecture, presented May 7, was one of an ongoing Spring Webinar Series presented by the Lumen Christi Institute called “Reason and Wisdom in Medieval Christian Thought.”

To view any of the lectures, either past or still to come, visit here.

In somewhat briefly yet adequately sharing some of the background of Abelard and Bernard, Otten clearly differentiated the two Frenchmen. She noted that Abelard was a model for dialectic study of theology, or reasoning, among his contemporaries and one of the more brilliant teachers of the age.

Otten quoted Abelard as saying: “I proceed not through venerable tradition, long practiced, but I proceed through my talents.” She followed that with this explanation:

What he opposes there is the weight of tradition, which really had become a weight by that time in which you couldn’t see the forest for the trees, and (he advocated for) his own keen insights, which he thought would give him a new opening of that tradition.

Education wasn’t formalized or institutionalized at that point in the 12th century, which meant teachers often “had to make it on their own, which offered great opportunities,” the professor observed. “It also created many, many pitfalls. And Abelard was the victim of that as well.”

Those pitfalls included some of what led to his antagonizing Bernard somewhat later in his life, but his approach to learning had a more lasting effect that some of these specific conclusions. Otten continued that Abelard felt “the way to begin inquiry into truth is by doubting. By inquiry do we perceive truth.” She said he likened such an approach to the way a 12-year-old Jesus spoke with Jewish teachers in the temple.

Among other theological truths, Abelard focused in particular on the doctrine of the Trinity, which he saw as an essential tenet of the Christian faith. He relied on the dialectical tool of analogy in explaining that truth.

“Abelard said there is a person who speaks, a person to whom he speaks and a person about whom he speaks,” Otten explained.

The New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia calls Abelard “the most eloquent and learned man of the age after Bernard.”

Otten introduced Bernard by saying “if there ever was a mysterious figure in the history of Christian thought, it was Bernard.” She described him as somewhat of a paradox at times, a monk who was “always on the go,” and radical in his reform of monastic life in part by looking backward and adhering more precisely to the Rule of Benedict.

Unlike Abelard and his insights from reading the Bible, Bernard leaned heavily upon Tradition, Otten said. “He actually ridiculed Abelard. He said ‘We don’t need a gospel of Peter (Abelard), we already have the four Evangelists.”

Bernard saw the gospels not as something from which to glean insight as much as something alive and very real. Instead of reasoning, the saint developed his theology by embracing the drama of the Bible. Otten didn’t consider Bernard an imitator; she called him a master.

“His rhetoric punches you in the stomach, if you will, it draws you in,” she said. “You almost cannot escape it.”

The purpose: to change the way monks, and indeed the entire Church, approached thinking about God and the Christian faith. Perhaps only in the history books can they be remembered as enemies. Ironically, both of them were influenced heavily by the Church Fathers. Otten called Bernard “the last of the Fathers” while saying Abelard “does the Fathers justice. He builds on them; he stands on their shoulders.”

“They were thinking along similar lines of reform, both in monastic and intellectual ways,” the professor said. “But they were following very, very different paths.

“They were two masters of their own craft, from two different traditions.”