Pope John Paul II called racism a plague, its manifestation in the United States “one of the most persistent and destructive evils of the nation.”

For the millions who experience racism, it can be encouraging to get to know Saints who were also targets of abuse, disdain, and even murder because of their race; ugly as some of these stories are, they remind you that you are not alone. For those of us who are trying to walk in solidarity with people of color, the stories of the Saints invite us to work harder to fight against racism in the Church and in the world.

Bl. Peter Kibe (1587-1639) was a Japanese Christian who felt called to be a Jesuit priest. He was refused entry to the Jesuit order in Japan and eventually went to Portuguese Macao. There, he was told he couldn’t be ordained because he was Japanese. He went to Goa, where he was told they wouldn’t ordain any Asians at all. Rather than wash his hands of the whole racist affair, Kibe trusted in what he knew of the Catholic Church (and the Jesuit order) and traveled to Rome, a journey that included 3,700 miles on foot. There, he was finally received into the Society of Jesus and ordained, after which he spent eight years traveling back to Japan to serve as an undercover priest before his martyrdom.

Ven. Teresa Chikaba (1676-1748) was, like St. Josephine Bakhita, kidnapped and sold into slavery as a child (though Chikaba was from Ghana). Though relatively well-treated in the home of her noble Spanish mistress, Chikaba remained an enslaved person. She endured the dehumanizing nature of slavery as well as the racist taunts and beatings at the hands of other servants in the household. Freed after the death of her mistress, Chikaba was turned away by one convent after another, despite her enormous dowry and the patronage of her former master the marquis. When she was finally allowed to enter a Dominican convent, she was made to live as a servant rather than a full-fledged nun, even after she became a mystic and a miracle-worker. A poet, Chikaba was the first black woman known to have written literature in a European language.

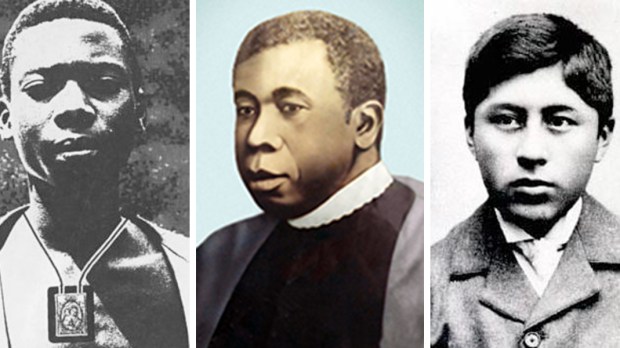

Bl. Francisco de Paula Victor (1827-1905) was born into slavery in Brazil, his father unknown. As a teenager, he told the tailor to whom he was apprenticed that he hoped to become a priest. The white man didn’t laugh at the aspirations of a black boy—he dragged Francisco into the street and beat him bloody. But the young man persisted, convincing his bishop (Ven. Antônio Ferreira Viçoso, a staunch abolitionist) to accept him as a seminarian. The only black man in the seminary, Francisco endured ridicule and disdain, but his evident holiness gradually silenced his racist classmates. When he was ordained, though, many of his white parishioners refused to receive Communion from his hand. Again, Fr. Francisco sought holiness; by the end of his tenure, his people adored him. But he wasn’t always the quiet, humble priest. When he was slighted, he was happy to turn the other cheek; but when others were in danger, he would stand up and shout. Once, a mob of armed men came to town intent on burning down the home of an abolitionist. Fr. Victor stood at the entrance to the town holding up a crucifix to show these men the bloodied face of their Savior who had become a slave for them. “Come in!” he shouted. “Come in! But come over the corpse of your priest.” They retreated and many lives were saved that night.

Bl. Ceferino Namuncurá (1886-1905) was a member of the Mapuche tribe, an indigenous people living in Chile and Argentina. The son of a chief, he was sent to be educated at schools where he was the only indigenous person. Some of his classmates were deliberately cruel, but most simply didn’t see the problem with making racist jokes. One, in all sincerity, asked Ceferino what human flesh tasted like. The young Mapuche just turned away, crying quietly. Ceferino entered the Salesian order, hoping to become a priest, but died of tuberculosis when he was 18.

Bl. Isidore Bakanja (1887-1909) was a Congolese Catholic who worked as a domestic servant on a rubber plantation. Isidore spoke often of his love for the Lord and longed to introduce all those he knew to Jesus. This made him an object of suspicion to his Belgian employers, who hated the Catholic faith, not least because Catholic missionaries insisted on teaching Africans that they were not inferior to white men. Because he refused to take off his brown scapular, Isidore was horrifically beaten by his white employer and left to die. He was a martyr for the faith, but his murder was only possible because as a black man he was considered disposable.

Read more:

Father Tolton recognized as venerable; may be first black American to be canonized