A few days ago I went to look through the works of St. Augustine to satisfy my curiosity about a particular question. I wanted to see if and how he had talked about regional epidemics (in the course of his life there were no pandemics), since it had never occurred to me to study the subject. I was surprised, but not too much so, to see how in his work (in Latin) the words virus, morbus, contagio and pestis almost never refer to clinical phenomena, but nearly always to heresies—that is to say, doctrinal aberrations (and sometimes even to disciplinary deviations).

Worldliness, a subtle plague …

In previous centuries, Christians sought to protect themselves from the “plague” of paganism. Augustine was born in 354, after Christianity had become legal, so the persecutions of the Roman Empire against Christians were for him an object of academic study, not of direct experience. Paganism was waning.

An “epidemic” of a different kind still arose, however—many, actually. First of all, there were heresies (and as with heresies, there were plenty of options to choose from), but also and especially there was an epidemic of secularization, which invaded all the Christian communities with the end of the persecutions. Being Christian was no longer inconvenient; on the contrary, it was beginning to be an advantage for career purposes. If in daily life one did not live coherently with the profession of faith, it mattered little, since more or less everyone lived the same way.

This was intolerable for many who, to escape this plague, gave life to the first forms of Christian monastic experience: St. Anthony the Great, whose life was told by Athanasius, and then Pachomius and many others. Secularization, however, was inexorable and did not spare monasteries, either. Precisely because of their reputation for holiness, monks were immediately called to play important pastoral roles (they were made bishops or even patriarchs), and this meant that many entered the monastery motivated by career ambitions. The most severe and austere among the monks reacted by seeking ever more intense forms of penance, forms sometimes so extreme that the Church remained doubtful for some time as to how to judge them. There were those who scourged themselves, those who fasted for long periods of time, those who hid in inaccessible hermitages … and even those who took refuge on top of columns!

Life of Simeon

This was the idea that Simeon had, for example. He was born when Augustine—from a completely different part of the world—was 35 years old, led a cenobitic monastic life, and was about to be ordained a priest (the following year). Simeon was the son of Martha, a very pious woman (also a saint). He entered a monastery when he was still an adolescent. He was so austere in his penances (he was one of the first to make himself a hair shirt), that he embarrassed the monks—who were neither bad nor indolent (they ate only once every three days!), but who were sworn to ἐσυχία, that is to say, to tranquility of the soul—and he was removed from the monastery.

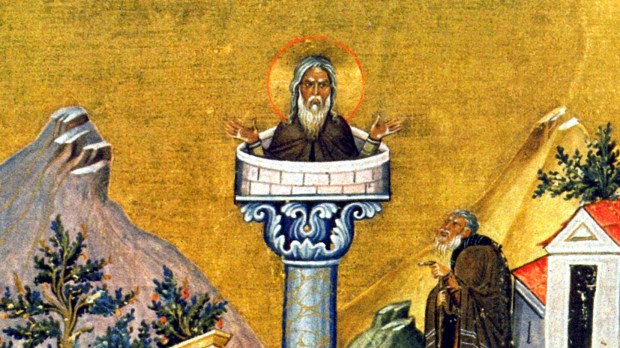

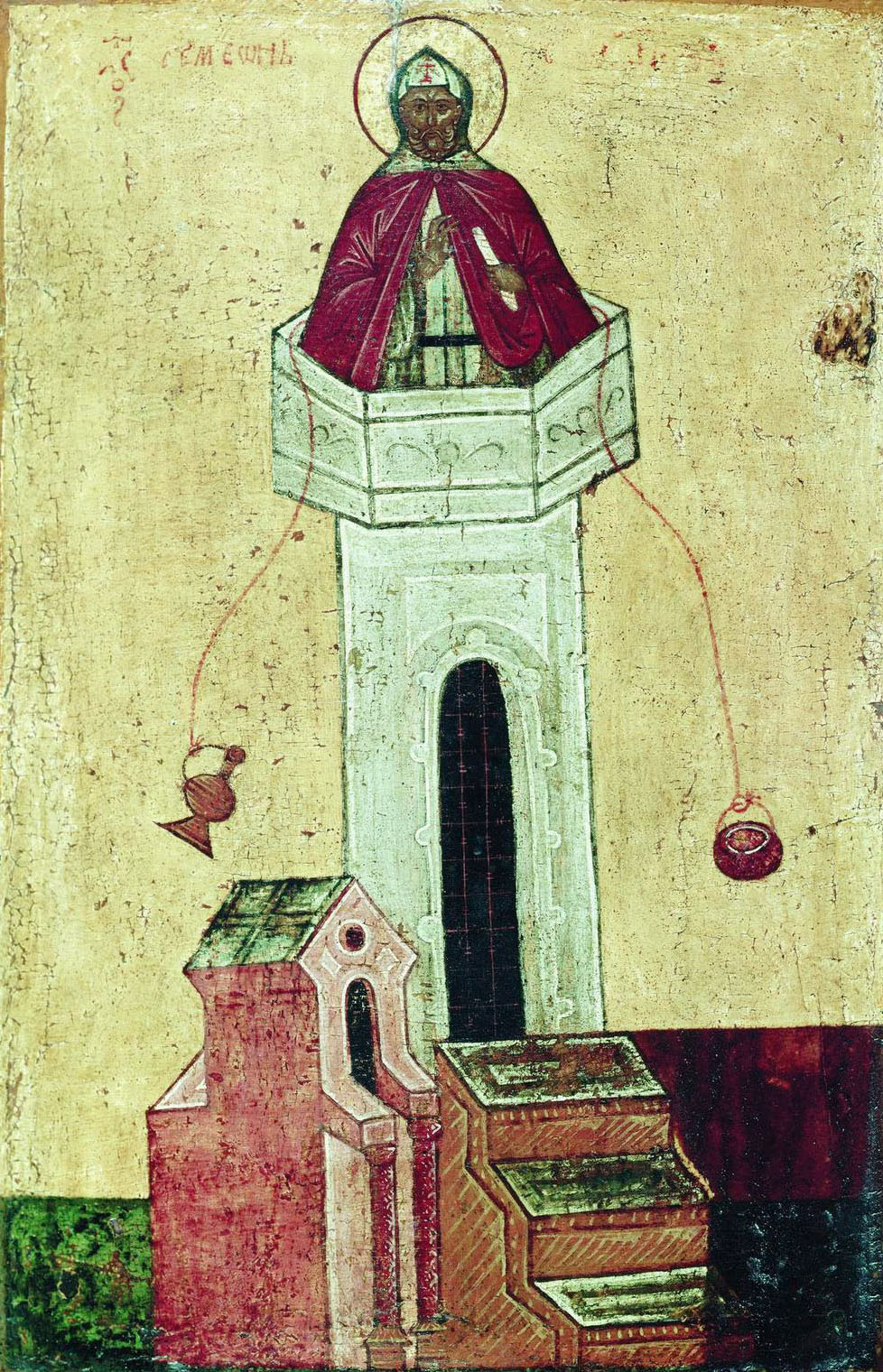

Simeon then intensified his penitential practices, spending all of Lent for the first time in one long fast (he was found unconscious at Easter and a step away from death: they revived him and gave him communion). He then went to take shelter on the mountain known today as Sheik Barakat, and since his reputation for holiness attracted large crowds of people, he looked for places where he could stay in peace (and safe from the contagion of worldliness!) for as long as possible. Eventually, he came up with the idea of climbing to the top of a large pillar, about four meters (13 feet) high. The icons depict him simply sitting at the top of the column, as if he were the capital of the pillar; contemporary sources tell us instead that a very small platform (a few square yards in area) was placed on top of the column.

Simeon descended several times from the column, but often only to climb an even higher one—from the top of which, however, every afternoon he agreed to meet the people who came to consult him (excluding women, lest he be tempted). There, he feared the mundane contagion could be irresistible, even for a man whose sensuality could be assumed to have been tamed by decades of fasting and exposure to the weather. “If we are worthy,” he is said to have told his mother, who had asked to see him (and who accepted the answer), “we will see each other in the next life.”

Stylite-influencer

Around the column, a group of devotees gathered and dedicated themselves to assisting the stylite (from the Greek for person on a pillar), who was not so far away from the events of ordinary folks, despite being perched 15 yards above them (that was the height of the last column he inhabited in his lifetime). Emperors, and saints at least as far away as Paris, knew of his fame and were eager for his advice.

After 37 years of living on a pillar, Simeon died in 459, inaugurating (like any self-respecting influencer) an ecclesial lifestyle to escape the contagion of worldliness in even its mildest and most “venial” forms. It was adopted not only by “Simeon the Younger,” who also bore the same name as the proto-stylite, but by many others who followed his extreme Christian lifestyle, for a full century.

In short, Simeon is someone to know in these days of forced quarantine that to some people seem too long. “To keep oneself unstained by the world” (James 1:27) is a good hygienic rule, and not only in times of medical epidemics.