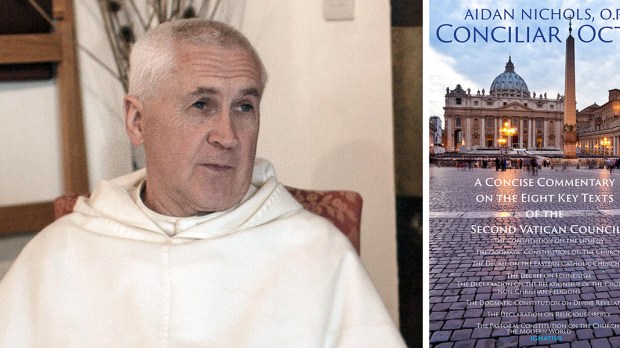

Conciliar Octet: A Concise Commentary on the Eight Key Texts of the Second Vatican CouncilBy Aidan Nichols, O.P Ignatius Press, 2019

Oh, no. “Not another book on the Second Vatican Council!”

Had I been his copy editor “oh, no” would have been included in Fr. Nichols’ first sentence, just for the jazzy horror element. But that’s me. Fr. Nichols’ – a Dominican priest and currently the John Paul II Memorial Visiting Lecturer, University of Oxford – actual first sentence does just as well and his commentary thereafter on the Vatican II documents is otherwise restrained and does represent “a concise commentary,” as the subtitle promises.

I said restrained, didn’t I. This is something of a departure from other approaches to Vatican II I’ve run across, shaped in other hands.

There are two main avenues of travel, reading the documents as progressive or traditionalist. Fr. Nichols for the most part ignores both and aligns with neither. Instead, Vatican II as he views it is Catholic orthodoxy, a magisterial teaching document, a document of texts that say what they say, produced from within the established theological tradition of the Catholic Church.

The progressive approach, my somewhat whimsical conclusion, is that the Vatican II Council did not go far enough and progressives are here to help push it to its proper finale. The traditionalist sentiment is considerably harsher but they are here to eradicate the non-traditional elements in the documents themselves. Both read for what they want, not for what the texts say.

Ironically, both progressive and traditionalist do agree: Vatican II messed with the Church, which is happy news to the first, heresy to the second.

Progressives, suggests Fr. Nichols, revisit “the Council so as to tell again the story of their liberation from the ancient pharaoh of the older Catholicism …” The Council is viewed as an abrupt rupture in the Church of history, making it absolutely the best thing that ever happened since the descent of the Holy Spirit.

Progressives have rediscovered a lost continuity with the real Jesus, whatever the texts may or may not in fact actually say. In fact – my impression – if Jesus had better defenders in the Council, the documents would say exactly what progressives say it says. The Council represents a coming Catholic era shorn of fussy traditionalist restraints, summarized by what is called the ephemeral “spirit” of Vatican II.

The nice thing about having the “spirit” of the Council is that it may be made to say anything since in fact it definitively says nothing. That – I have perhaps exaggerated a bit more than Fr. Nichols would appreciate – is a progressive interpretation of Vatican II.

A traditionalist interpretative approach is equally edgy. When Catholic traditionalists see Vatican II, says Nichols, sometimes they “can find in the Council nothing more than a damnable débâcle.”

That characterization is a mild sentiment, compared to a few of the web sites I’ve stumbled across describing Vatican II as “satanic spawn.” I do not know how honest Catholics pick and choose their way through the declarations. I’d say this to both: They resemble dyspeptic diners picking over a buffet.

Somewhere between these two approaches we find orthodox Catholics, a term Nichols does use though not in the sense of finding a moderate middle-ground for Catholics; his book is neither polemical nor a call to arms. What he seeks are “orthodox Catholics, willing to revisit the texts in a better frame of mind than that of their liberal rivals.” I think he should have included traditionalist conservatives in that, as well; perhaps even baffled Catholics. For the record, he does speak more of progressives than traditionalists.

Yet where both traditionalist and progressive have it otherwise, the Council was not a break with the past. It was a council where the Church Fathers – with debate and sometimes demanding argument – produced a “council of texts.” If you wish to know what the Council said, one then must read what the Council said.

Nichols’ effort is to treat the documents as texts. The Council produced documents, texts, the words of Vatican II. In Nichols’ view there is the only way to go about interpreting what was said by the Church Fathers. Read the words. One must remember that whatever the differences among the Fathers, and they certainly were present, nonetheless, the Fathers agreed to the texts that formed the document that found the Council’s approval. There is little else to say.

Each chapter is an expanded commentary on each of the eight major texts. They lead the reader briefly through the background, some of the debate, but it is thorough. Octet is short given the complexity of the subject, the eight key declarations of the Council, and comes in at only 163 pages of text plus 14 pages of index. He is a cheerful writer, and a widely published one at that.