Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

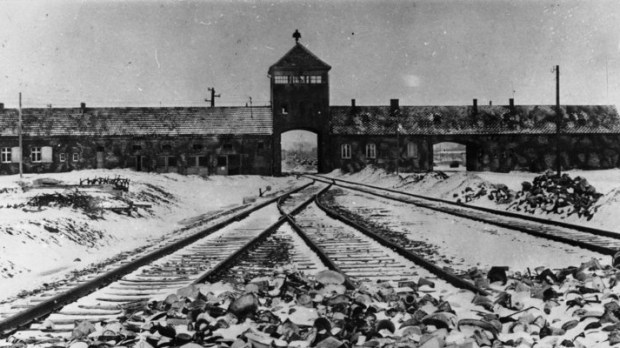

“Never again!” has become an everlasting cry in response to the mass killing of Jews in Europe during the Second World War, and remembrance has become a perennial action to honor the victims of the Holocaust.

But whether the Catholic Church did enough to fight this injustice, and whether Pope Pius XII remained silent in the face of the Nazi atrocities, have also become perennial questions.

A panel of historians and other experts tackled some of those questions at a United Nations event marking the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the death camp at Auschwitz on Monday. The three-hour discussion, “Remembering the Holocaust: The Documented Efforts of the Holy See and the Catholic Church to Save Lives,” came at the beginning of a year when the world will mark the 75th anniversary of the end of the Second World War and the establishment of the U.N. itself. And on March 2, the Vatican will make all archival materials pertaining to Pius’ pontificate (1939-1958) accessible to scholars.

Johan Ickx, director of historical archives in the Holy See’s Section for Relations with States, gave an overview of what will be available to scholars beginning March 2, including the Apostolic Archive, previously known as the Secret Archives; archives of the nunciatures during the Second World War; documentation of various dicasteries; papers related to rescuing people; and archives of the Propaganda Fide dicastery, which include papers of the missions around the world, such as those in war zones.

Ickx said that the archives of the Holy See’s Section for Relations with States, for which he is responsible, have been undergoing a process of digitization for the past eight years.

Questions about Pius XII’s alleged silence—and even cooperation with Hitler’s goals—began when a German playwright published a stage piece in 1963 called The Deputy. Ronald Rychlak, author of Hitler, the War and the Pope and Disinformation, explained that after WWII, the atheistic Soviet government “found itself with dominion over deeply Christian nations in Central and Eastern Europe. In order to advance their communist doctrines, Soviet leaders would have to undermine the Church. The best way, of course, would be to associate it with the Nazis. On June 3, 1945, Radio Moscow announced that Pius XII had been Hitler’s Pope and suggested that he had been an ally of the Nazis during World War II.”

Europeans, however, knew Pius for his humanitarian response to the sufferings of the war, and wouldn’t buy the Soviet argument. “The Soviets would have to find another way, and that came when a play came out after his death,” Rychlak said.

Prior to The Deputy’s debut, there was a general consensus, even among Jewish leaders, that Pius had acted honorably during the war. Gary Krupp, founder of the Pave the Way Foundation, which cosponsored the event with the Holy See Mission to the United Nations, said that an internet search of newspapers from 1939-1958, revealed that “the most prominent Jewish personalities of the era praised the actions of the Church, and specifically Pope Pius XII. Golda Meir, Albert Einstein, all the major Jewish organizations, the chief rabbis of Rome, of Egypt, of Palestine, of Romania, of Denmark and many more showered the Catholic Church with unreserved praise.”

Pius’ documented actions, outlined by panelists, contradict the picture painted by The Deputy and books such as John Cornwell’s Hitler’s Pope. Ickx, for example, said that during the Nazi raid on Rome on October 16, 1943, Pius “was not looking from his window doing nothing.” His interventions resulted in the halt of deportations to Auschwitz, although not before 1,030 Jews were already deported.

“Written testimonies confirm it was on the order of the pope to give shelter to the Jews” in 235 convents and monasteries in Rome, Ickx said. “Altogether, Pius can be credited with the rescue of two thirds of the Jews who were present in the city at the end of the war.”

Perhaps nothing was more dramatic, however, than Pius’s involvement in plots to get rid of Hitler, according to the research of Mark Riebling. Riebling’s book, Church of Spies, in fact tells such a dramatic story that it is being made into a movie.

That story begins in October 1939, when Pius was approached by dissident officers in the German military.

“They worried that if Hitler won the war, the Nazis would destroy the aristocracy and Christianity and many other things that conservative Germans held dear,” Riebling told the New York UN audience. “These dissident Germans wanted to eliminate Hitler and do a peace deal with the Western allies. These conscientious Germans wanted Pius XII to be their secret foreign agent, partly because of his public impartiality and partly because of his reputation for discretion. These plotters considered Pius the one trusted power among powers no one could trust. Somewhat to the amazement of the German resistance, Pius XII was all in.”

Pius at first was a conduit between the British government and the German resistance,” Riebling explained. “Gradually, the Holy Father’s role expanded to where he was not just a mediator but an active plotter. … By the war’s end Pius had participated in three plots to remove Hitler. In all three, he had midnight meetings in the papal apartments with British diplomats, trying to bring up a coup in Berlin.”

All three of the plots failed, however.

Riebling contested the depiction of a “silent” pope in the face of the Holocaust.

“I personally would not call it a silence so much as being careful with words,” he said. “The pope denounced the murder of anyone on the basis of race, especially in his 1942 Christmas address. At the same time, Pius tried to avoid criticizing Hitler or the Nazis by name. Documents in the Roosevelt library show the German resistance asking Pius not to decry Nazism from the mountaintop, fearing that such criticism would cause a crackdown on resistance elements. [The German plotters’ emissary to the pope, Josef] Mueller said that his ‘anti-Nazi organization in Germany had always been very insistent that the pope should refrain from making any public statement singling out the Nazis since, if the pope had been specific, Germans would have accused him of yielding to the promptings of foreign powers and this would have made the German Catholics even more suspected than they were and would have greatly restricted their freedom of action in their work of resistance to the Nazis.’ Dr. Mueler said the pope had followed this advice throughout the war.”

Introducing the panel discussion, the new Permanent Observer of the Holy See to the United Nations, Archbishop Gabriele Caccia, commented, “The Holocaust was a time when the world lived in darkness, but there were points of light, represented by good people who tried to help those in trouble.” An event such as this panel discussion, he said, helps us understand that “if we are not indifferent to the suffering, to the injustices, to the wounds of the world, we can make a difference.”