Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

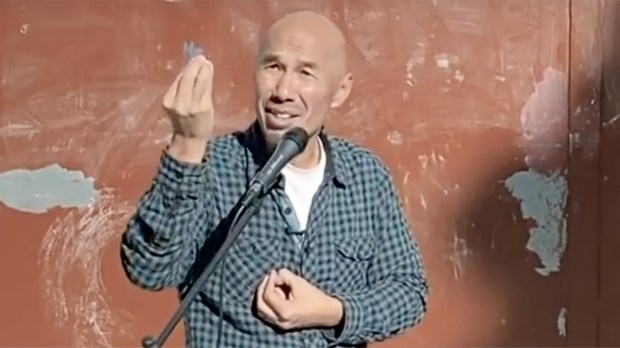

Evangelical pastor Francis Chan recently made

about the unity of the Christian church, the Real Presence, and the centrality of communion:I didn’t know that for the first fifteen hundred years of church history, everyone saw [communion] as the literal body and blood of Christ, and it wasn’t until five hundred years ago that someone popularized a thought that it’s just a symbol and nothing more … For fifteen hundred years it was never one guy and his pulpit being the center of the church; it was the body and blood of Christ … I’ve been dreaming about this. I’ve been praying about this, going, man: I would love it if one day in our country, here in the US, people understood the body of Christ, that they were just a part of it, and they got excited to gather and partake of the body and blood of Christ.

In

posted just this week, he continues to explore this new direction: “I’m supposed to preach the Gospel by taking communion? That’s what [Jesus] said … For fruit that lasts, I think we need to rethink this … Let’s bring communion back to the forefront.”Not surprisingly, his original comments drew some heat from fellow Protestants.

, for example, criticized Chan for glossing over the nuances of history. But in a thoughtful response , he notes that even non-Catholic historian J.N.D. Kelly and Catholic critic William Webster both offer histories of Eucharistic teaching that essentially mirror Chan’s.It’s worth noting that in the

, Chan begins not with history but with Scripture. There are two verses, he admits, that “always bothered” him with respect to communion. The first is Acts 2:42: “They devoted themselves to the teaching of the apostles and to the communal life, to the breaking of the bread and to the prayers.” (Later in the chapter we read: “Every day they devoted themselves … to breaking bread in their homes,” a model Chan has tried to revive with his “We Are Church” movement.) The second was 1 Corinthians 11:27: “Therefore whoever eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord unworthily will have to answer for the body and blood of the Lord.” Why, if the bread was a symbol, were the disciples so devoted to it? And why did Paul speak about eating it with words of such dire warning? These passages are certainly worth reflecting on—especially, I would add, in light of the Bread of Life Discourse and Last Supper scenes in the Gospels—and offer a serious challenge to a merely symbolic view of communion.The writings of the Church Fathers, the earliest Christian writers after the Apostles (e.g., Polycarp, who was taught by John), offer a further challenge. Here is a sample of four quotations from the first four centuries of the Church.

St. Ignatius of Antioch (35-108) on the early heretics the Docetists:

They abstain from the Eucharist and from prayer because they do not confess that the Eucharist is the flesh of our Savior Jesus Christ, flesh which suffered for our sins.

Justin Martyr (100-165) in his First Apology:

Since Jesus Christ our Savior was made incarnate by the word of God and had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so too…the food which has been made into the Eucharist…is both the flesh and the blood of that incarnated Jesus.

Gregory of Nyssa (335-394):

The bread again is at first common bread; but when the mystery sanctifies it, it is called and actually becomes the Body of Christ.

And Augustine (354-430), one of the greatest theologians in Church history:

That Bread which you see on the altar, consecrated by the word of God, is the Body of Christ. That chalice, or rather, what the chalice holds, consecrated by the word of God, is the Blood of Christ. Through those accidents the Lord wished to entrust to us His Body and the Blood which He poured out for the remission of sins.

Augustine goes on to draw out the same implications of Church unity drawn out by Chan:

“The bread is one; we though many, are one body.” So, by bread you are instructed as to how you ought to cherish unity. Was that bread made of one grain of wheat? Were there not, rather, many grains?

But what’s fascinating about Chan’s sermon is that he is not putting forward a particular position about communion, but opening up a difficult conversation about what it means to follow Christ more closely. He is not looking to debate transubstantiation vs. consubstantiation, or Catholic vs. Reformed theology—important and clarifying though these more recent debates are—but squarely facing an open wound, a glaring disconnect with the first thousand years of Christianity. In an age of rampant unbelief and demonic scattering, he is asking: Why did Jesus and so many of his followers so highly value communion—and unity, with which it seemed so tightly linked? Why don’t we? What are we missing out on?

These are questions very much worth asking. And I hope he, and all Christians, continue to ask them.