Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

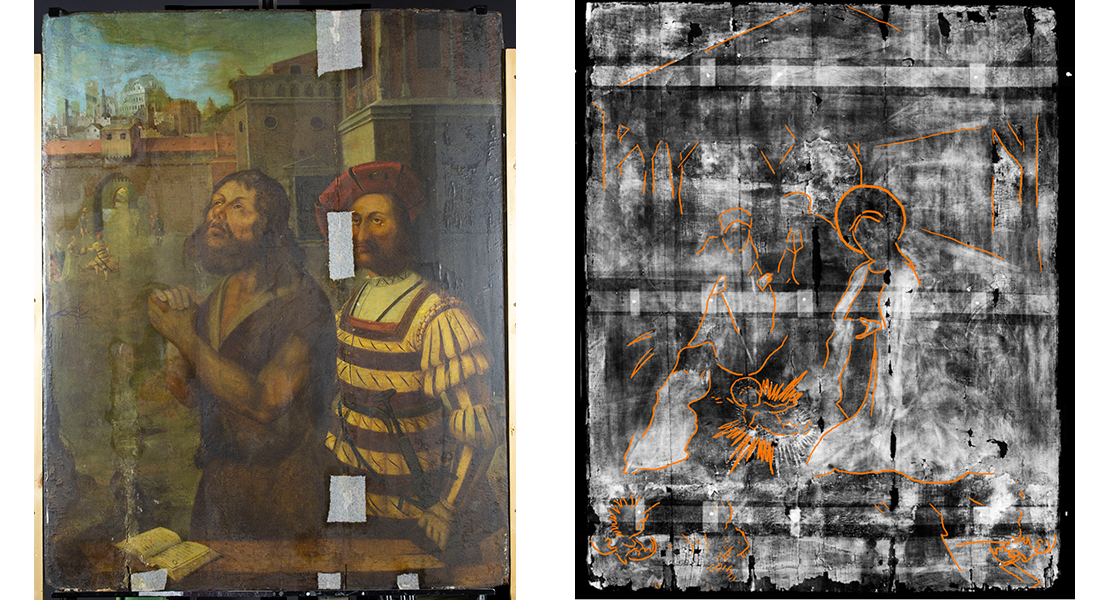

Art conservators have discovered a hidden Nativity scene painted just beneath the surface of a 16th-century depiction of the beheading of St. John the Baptist.

And they made the discovery just before Christmas.

The experts, from Northumbria University in Newcastle, England, have been working with The Bowes Museum near Durham to examine the painting, “St. John the Baptist,” and work on its restoration. An X-ray of the artwork revealed another image underneath, featuring angels with halos, a baby in a manger and the outline of what appears to a stable.

“Before looking to carry out any conservation treatment it was thought necessary by the museum staff and myself to carry out full technical examination so that we might have a better understanding of its structure and perhaps have a clearer idea as to why it was in such poor condition,” Nicola Grimaldi, senior lecturer in Conservation of Fine Art at Northumbria, told Aleteia. “X-radiography is just one of the methods I used to examine the painting and performed only in the last few weeks, but I was completely taken aback to find the Nativity scene (a completely different image) lying beneath the present image of St. John the Baptist.”

She said that the artist of the painting is not known.

Grimaldi told Medievalists.net that it is unusual to find paintings hidden in this way and to discover a Nativity scene in this detail.

“And just before Christmas was really incredible,” she said.

Grimaldi said she and her team were trying to understand why there was significant loss of paint in parts of the work, particularly where the wood behind the canvas joined together.

“The first stage of most investigations of this kind is to carry out an X-ray to understand what is going on underneath the layer of paint we see on the surface,” she said. “That was when we realized there was more to the painting than we originally thought.”

Medievalists.net noted:

The X-ray showed up several figures, including the outline of what appears to be one of the three wise men, or Magi—his hands outstretched as if holding out a gift. Also clearly visible is the outline of a baby in a manger with a halo around his head. Grimaldi adds: “It was common practice to apply gold leaf to these type of religious paintings and in the X-ray we can see that gold is present in the halo around the baby’s head.

“Incredibly we can see lines over the X-ray image which we believe to be preparatory drawings, showing where the painting was probably copied from an original drawing (cartoon),” she told the website. “Those lines were subsequently filled with another paint layer such as lead white which allows them to be visible on the X-ray.”

She told Aleteia that there seems to be no archival evidence to confirm why this the first painting was overpainted. “We can only speculate. However there could be a number of reasons, from the reusing of artists’ materials (a good solid panel simply reused), damaged, or poor condition of the painting, or incomplete work (completed by another hand).”

“Since this is such a recent discovery I am still working on the examination and interpretation of this painting, which will take several months to complete,” she continued.

Asked whether there might be a decision to remove the overpainting to expose the original, she said that that would have to be with the full agreement of the museum. “These days, such a radical treatment would have to be carefully thought through, and most museums are unlikely to remove one painting to reveal another,” she said. “If further funding was available there may be other methods of technical imaging we could carry out; however, that would involve moving it, involving careful further transportation and handling.”

Medievalists.net said the team plans to carry out a chemical analysis of the paint, using Northumbria’s state-of-the-art equipment and techniques, including a scanning electron microscope, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy and infrared reflectography.

Said Jane Whittaker, Bowes Museum head of collections, “We’re simply delighted and astounded to discover that this 16th-century work was hiding such a wonderful secret and to find out at this time of year is really quite fortuitous. It’ll be really interesting to find out more about it as Northumbria University continue their investigations.”