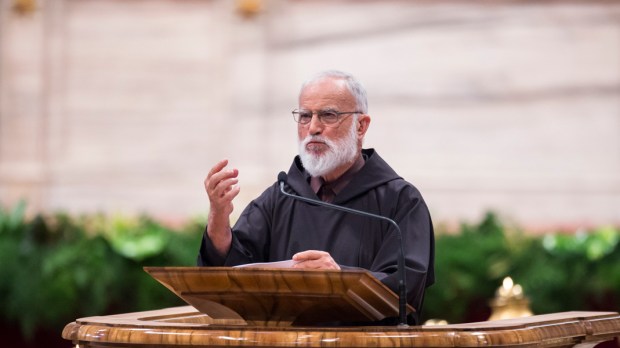

Here is the second Advent homily of 2019 given by the preacher of the Pontifical Household, Capuchin Father Raniero Cantalamessa.

~

In this meditation we go with Mary “into a hill country” and enter into the house of Elizabeth. Mary speaks to us personally with her canticle of praise, the Magnificat. Today the Catholic Church celebrates the priestly golden Jubilee of the Successor of Peter and the canticle of Mary is the prayer that most spontaneously springs from the heart in a circumstance like this. A meditation on it is our little way of celebrating the event.

To understand the place and the meaning of the canticle of Mary we need to say something about the canticles in general. In the Gospels of the infancy of Jesus these canticles – Benedictus, Magnificat, Nunc dimittis – are there to explain what came about in a spiritual way, that is, to enhance the meaning of the events –the Annunciation, the Visitation, Christmas – making them a form of confession of faith and praise. They stress the hidden meaning of the events which must be brought to light.

As such, they are an integral part of the historic narration and not just interludes or separate passages, because every historic event is made up of two factors: the event and the meaning of the event. It has been written that “the Christian Liturgy begins with the canticles of the story of the infancy.” (H. Schürmann). In other words, these canticles contain the Christmas liturgy in an embryonic stage. They are the fulfillment of the essential element of the liturgy which is a joyful celebration of belief in the event of salvation.

Many problems remain unsolved about these canticles according to the biblical scholars: the real authors, the sources, the structure. Fortunately, we can leave all these problems to the critics who continue to study them. We don’t have to wait for these obscure points to be solved to be edified by these canticles. This is not because these problems are of no importance but because there’s a certainty which makes all these uncertainties less important. Luke accepted these canticles in his Gospel and the Church has accepted Luke’s Gospel in its Canon. These canticles are the “Word of God” inspired by the Holy Spirit.

The Magnificat is Mary’s because the Holy Spirit attributed it to her and this makes it more “hers” than if she had actually written it herself! In fact, we are not really interested in whether Mary composed the Magnificat or not but in knowing whether she composed it under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. Even if we were certain that Mary composed it, we wouldn’t be interested in it because of this but because it is the Holy Spirit who speaks through it.

Mary’s canticle is a new way of seeing God and the world. In the first part which embraces verses 46-50, following what has come about in her, Mary’s glance is turned towards God; in the second part which embraces the remaining verses her glance is turned towards the world and history.

A new look at God

The first movement in the Magnificat is towards God; God has absolute primacy over everything else. Mary doesn’t delay in answering Elizabeth’s greeting, she doesn’t either enter into discourse with man, but with God. She recollects herself and immerses herself in the infinite God. An incomparable experience of God has been “fixed” in the Magnificat for all time. It is the most sublime example of the so-called numinous language. It has been observed that when the divine reality is manifested to a soul it usually produces two opposing sentiments: fear and love, awe and attraction. God shows himself as a “tremendous and fascinating mystery,” tremendous in his majesty, fascinating in his goodness. When God’s light first shone on him, Augustine confessed: “I trembled with love and terror” and even later on contact with God made him “shudder and burn” at the same time.[1]

We find something similar in Mary’s canticle, expressed biblically, through the titles used. God is seen as Adonai (much more meaningful than the term “Lord” we translate it with), as “God,” as “Powerful” and above all as Qadosh, “Holy”: Holy is his name! At the same time, however, this holy and powerful God is all trusting, seen as “my Savior,” as being indulgent and lovable, one’s “own” God, a God for his creature. Above all it is the insistence on God’s mercy that brings to light his benevolence and closeness to mankind. “His mercy from generation to generation”: these words suggest the idea of God’s mercy as a mighty river flowing throughout all human history.

Knowledge of God provokes, as a reaction and contrast, a new and true perception and knowledge of oneself and one’s own being. The self is only grasped in front of God coram Deo. This is what happens in the Magnificat. Mary feels ”looked” upon by God; she herself enters into that look and sees herself as God sees her. And how does she see herself in this divine light? As being “small” (here “humility” means real smallness and lowness and not the virtue of humility!). She sees herself as a “servant.” She sees herself as a nothing that God has deigned to look upon. Mary doesn’t attribute the divine election to her virtue of humility, but to God’s grace. To think otherwise would mean to destroy Mary’s humility. This virtue has something special about it: has it who thinks he or she has not, doesn’t have it who thinks he or she has it.

From this acknowledgment of God, of herself and of the truth, spring joy and exultation: My spirit rejoices … the joy of truth bursting forth, joy for the divine work, a joy of pure and gratuitous praise. Mary magnifies God for himself, even if she magnifies him for what he has done in her; she magnifies him for her own personal experience, as do all the great biblical worshippers. Mary’s jubilation is an eschatological jubilation for God’s decisive action and it is the jubilation of the created being for being ceatures loved by their Creator, at the service of the Holy One, of love, of beauty, of eternity. It is the fullness of joy.

St. Bonaventure who personally experienced the transforming effects on a soul visited by God, speaks of the coming of the Holy Spirit on Mary at the moment of the Annunciation as a fire which inflamed all of her:

The Holy Spirit came upon her,” he wrote, “like a divine fire which inflamed her mind and sanctified her flesh conferring on her a most perfect purity. … Oh, if only you were able to feel in some measure how great was the fire that descended from heaven and how wonderful it was, what freshness it brought. … If you could only hear the Virgin’s jubilant hymn.[2]

Even the strictest and most exacting scientific exegesis is aware that we are dealing with words that cannot be comprehended through the normal means of philological analysis and admits that: “Whoever reads these lines is called to share in the jubilation; only the celebrating community of those who believe in Christ and those faithful to him are able to comprehend these texts.” It is speaking “in the Spirit” and cannot be understood if not in the Spirit.

A new look at the world

As I said, the Magnificat is made up of two parts. What changes between the first and the second parts is not the language used, neither is it the tone. From this point of view the canticle is an uninterrupted flow with no breaks; the verbs continue to be in the past tense narrating what God has done or, better still, what he “has started to do.” Only the background of God’s action has changed; from what he did “in her” we pass to what he did for the world and for history. The effects of the definitive manifestation of God and how it reflects on humanity and history are dealt with.

Here we have a second characteristic of evangelical wisdom, that of uniting sobriety in the way of looking at the world to the inebriation that contact with God gives, in conciliating the greatest rapture and abandonment to God with the greatest critical realism towards history and man. In the second part of the Magnificat, after exulting in God, Mary turns her penetrating gaze on what is happening in the world.

Using a series of powerful aoristic verbs, from verse 51 on, Mary describes a pulling down and a radical reversal of men’s positions: he pulled down—he raised; he filled— he sent empty away. An unexpected and irreversible turn of things because it is God’s work and God never changes or goes back on his word as man does. In this changeover two different groups emerge; on the one hand the proud- powerful-rich, on the other the humble-hungry. It is important to understand this reversal and where it started if we are not to misunderstand the whole canticle and with it the evangelical beatitudes which are anticipated here in almost the same words.

Let us look at history: what actually happened when the event Mary sung of started to be fulfilled? Was there perhaps an external social revolution through which the rich were suddenly impoverished and the hungry filled with good things? Was there, perhaps, a more just distribution of riches among the social classes? No, not really. Were the powerful really pulled down from their thrones and the humble raised high? No. Herod continued to be called “the Great” and Mary and Joseph had to flee into Egypt because of him.

If what was expected was a visible, social change, history has taught us that this was not to be the case, where then did this reversal take place (because it did take place)? It took place in the faith! The kingdom of God manifested itself bringing about a silent but radical revolution. It is as if something had suddenly been discovered which caused an unexpected devaluation. The rich are like those who have amassed great wealth but who, on waking one morning, find themselves miserably poor because a hundred per cent devaluation had taken place overnight. On the contrary, the poor and the hungry are favored because they are ready to accept this new situation and do not fear the change it will bring about: their hearts are ready.

As I have mentioned, the reversal of things Mary sings of is similar to that proclaimed by Jesus in the Beatitudes and in the parable of the rich man. Mary speaks of richness and poverty starting from God; once again she speaks coram Deo; God, not man, is her measure. She establishes the “definitive” eschatological principle. To say therefore that we are dealing with a reversal “in faith” does not mean that it is any the less real and radical, or serious; it is infinitely more so. This is not a pattern created by the waves on the sand which the next wave will wash away. It is an eternal richness and an equally eternal poverty.

The Magnificat, school of evangelization

Commenting on the Annunciation, St. Irenaeus says that “Mary, full of exultation, prophetically exclaimed in the name of the Church: My soul magnifies the Lord.“[3] Mary is like the soloist who starts a tune that must then be taken up by the choir. This explains the expression “Mary, model of the Church” (typus Ecclesiae), used by the Fathers and acknowledged by Vatican Council II (LG 63). To say that Mary is “the model of the Church” means that she is the personification of the Church, the perceptible representation of a spiritual reality; it means that she is the model of the Church in the sense that the idea of the Church is perfectly realized first of all in her person and at the same time she is its principal member, its root and its heart.

But what meaning does “Church” have here and in the place of which Church does Irenaeus say Mary sang the Magnificat? Not in the place of the nominal Church, but of the real Church, that is, not of the Church in abstract, but of the actual Church, of the persons and souls who make up the Church. The Magnificat is not only to be recited but to be lived. Each one of us should make it our own; it is “our” canticle. When we say: “My soul magnifies the Lord,” the “my” should have a direct reference. St. Ambrose wrote: “May Mary’s soul be in you to exult in God. … If it is true that one only is the Mother of Christ according to the flesh, all souls generate Christ in the faith because each believer accepts in himself the Word of God.”[4]

In the light of these principles let us now try to apply Mary’s canticle to ourselves, to the Church and soul, to learn what we must do to “be like” Mary not only in words but also in deeds.

Where Mary proclaims the putting down of the powerful and proud, the Magnificat reminds the Church of the essential message it must announce to the world. It teaches the Church to be “prophetic.” The Church lives and practices the Virgin’s canticle when it repeats with Mary: He has put down the mighty from their thrones, the rich he has sent empty away! The Church repeats this with faith, making a distinction between it and all the other announcements it also has the right to make concerning justice, peace, and the social order in so far as it is the qualified interpreter of the natural law and the guardian of Christ’s commandment on fraternal love.

If the two views are distinct, they are not, however, separate and without reciprocal influence. On the contrary, the proclamation of faith of what God has done in the history of salvation (the view of the Magnificat) becomes the best indication of what man in his turn must do in his own personal history, and, rather, of what the Chinch itself must do on account of the charity it must show to the rich, in view of their salvation. More than “an incitement to pull down the powerful from their thrones to exalt those of low degree,” the Magnificat is a healthy warning addressed to the rich and powerful about the tremendous risk they run just as the parable of the rich man will later on be in the intentions of Jesus.

The Magnificat is not therefore the only way of facing the problem which is very much felt today of wealth and poverty, of hunger and having too much; there are other legitimate ways which come to us from history, and not from faith, and to which Christians rightly give their support and the Church its discernment. But the evangelical way must be proclaimed by the Church always and to all men as its specific mandate and through which it must support the common efforts of all men of good will. It is always universally valid and relevant. If by chance a time and place existed in which there was no longer any injustice or social inequality among men, but everyone was rich and satisfied, the Church would still have to proclaim, as Mary did, that God has sent the rich away empty. Actually, it would have to proclaim it with even greater energy. The Magnificat is just as relevant in rich countries as in countries of the Third World.

There are plans and aspects of life which can be grasped only with the help of a special light, the bare eye is not sufficient; we need infra-red or ultra-violet rays. The image this special light gives is very different and surprising to those who are used to seeing the same phenomena in a natural light. Thanks to the word of God, the Church has a different image of the world situation, the only lasting image, because it is obtained with the light of God and it is the image God himself has. The Church cannot keep this image hidden. It must spread it untiringly, make it known to all men because their eternal destiny is at stake. It is the image that will remain when the “pattern of this world” has passed. At times it must make it known through simple, direct and prophetic words, like those Mary used; in the way we express things we are intimately and serenely persuaded of. This must be done even at the cost of appearing ingenuous and cut off from this world according to the prevailing opinion and spirit of the time.

The Apocalypse gives us an example of this direct and bold prophetic language in which divine truth is opposed to human opinion: “You say (‘you’ could equally be the individual or a whole society): I am rich, I have prospered and I need nothing! not knowing that you are wretched, pitiable, poor, blind and naked” (Rev 3:17).

Think of the well-known story of Andersen in which some swindlers made a king believe that there was some beautiful material which would make those wearing it invisible to the foolish and stupid, and visible only to the wise. First of all the king himself does not see it but he is afraid to say so in case he is considered one of the foolish and all his ministers and his people behave in the same way. So almost completely nude the king parades through the streets and everyone, so as not to betray themselves, pretend to admire his beautiful robes until a child’s voice is heard in the crowd: “But the king has got nothing on!”, thus breaking the spell and everyone finally has the courage to admit that the famous robes do not exist.

The Church must be like that child’s voice. To a world infatuated with its own prosperity and which considers those who show they do not believe in it, it repeats the words of the Apocalypse: “you do not know that you are naked!” This shows us that Mary really “speaks prophetically for the Church” in the Magnificat: starting from God, she was the first to lay “bare” the great poverty of the riches of this world. By itself the Magnificat justifies the title “Star of the evangelization” St. Paul VI attributes to Mary in his “Evangelii nuntiandi”

The Magnificat, school of conversion

However, to limit the part of the Magnificat about the proud and the humble, the rich and the hungry to what the Church and believers must preach to the world would be to misunderstand it completely. We are not just dealing with something that must be preached but which, above all, must be practiced. Mary can proclaim the beatitude of the humble and poor because she herself is humble and poor. The reversal she talks about must take place especially in the heart of whoever says the Magnificat and prays through it. Mary says: God has scattered the proud “in the imagination of their hearts.”

Unexpectedly the subject shifts from outside to inside, from theological discussions in which everyone is right to the thoughts of the heart in which everyone is wrong. The man who lives “for himself,” whose god is his own “self” and not the Lord is a man who has built himself a throne on which he sits dictating laws to others. Now, Mary says, God has put those down from their thrones; he has laid bare their lack of truth and injustice. There is an interior world made up of thoughts, will, desires and passions, which, St. James says, cause the wars and fightings, the injustice and abuse which are among you (cf. Jas 4:1) and while no one tries to change this situation from the root, nothing will really change in the world and if something changes it is only to reproduce, in a short time, the same situation as before.

How closely then are we touched by Mary’s canticle, how deeply it scrutinizes us and how radically it “cuts the roots!” How stupid and incoherent I would be if, everyday, at Vespers, I were to repeat with Mary that God “cast the mighty from their thrones” while in the meantime I continued to hanker after power, a higher place, promotion, a better career and lost my peace of mind if I didn’t succeed; if everyday I were to proclaim with Mary that God “sends the rich away empty” and in the meantime I hankered tirelessly after riches and possessions and ever more refined things; if I were to prefer being empty-handed before God to being empty-handed before the world. How stupid I would be if I were to continue saying with Mary that God “raises the lowly,” that he is near to them while he keeps the proud and rich at a distance, and then did the very opposite. In his commentary to the Magnificat Martin Luther writes,

Every day we see that all men aim too high, at positions of honor, power, wealth, dominion, a more comfortable life, at anything which gives them importance. And we all like to be friends with such people; we run after them, serve them willingly, share in their greatness. No one wants to look down lower where there is poverty, disgrace, need, affliction and anguish. Rather, we turn our eyes away from such things. We shun and avoid those who are troubled and abandon them to themselves. No one thinks of helping or assisting them or of doing anything to help them become something; they must remain of low degree and be despised.[5]

Mary says that God does the opposite; he keeps the proud distant and raises to himself the humble and unimportant; he stays more willingly with the needy and hungry who harass him with supplications and requests than with the rich and satisfied who do not need him and ask nothing of him. Thus, with maternal tenderness, Mary exhorts us to imitate God and make his choice ours. She teaches us God’s ways. The Magnificat is truly a wonderful school of evangelical wisdom. A school of continuous conversion.

Through the communion of saints in the Mystical Body, the whole of this immense heritage now adheres to the Magnificat. This is the way it should be recited, in chorus with all the worshippers of the Church. This is the way God takes delight in it. To be part of this chorus which has developed throughout the centuries, all we have to do is want to represent to God the sentiments and transport of Mary who was the first to sing it “in the name of the Church,” of the scholars who commented on it, of the musicians who set it to music with faith, of the pious and the humble of heart who lived it. Thanks to this wonderful canticle, Mary continues to magnify the Lord for all generations. Her voice, like that of a coryphaeus, supports and carries along with her that of the Church.

A worshipper of the psalter invites us all to join him in saying: “Magnify the Lord with me ” (Ps 34:3). Mary repeats the same words to us, her children. If I am allowed to interpret his mind, so does also the Holy Father in the day of his priestly Jubilee: “Magnify the Lord with me!” And we promise to do it.

[1] Cf St. Augustine, Confessions, VII, 16; XI, 9.

[2] St. Bonaventure, Lignum vitae, I, 3.

[3] St. Irenaeus, Adv. Haer., III, 10, 2 (SCh 211, p. 118).

[4] Cf St. Ambrose, On the Virgins, I, 31 (PL 16, 208).

[5] Weimar ed., 7, p. 547.