Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

For almost 200 years, the greatest names in the pantheon of painting were eager to immortalize the leaders of their faith.

There are pictures of every pope from St. Peter to Pope Francis, but how many of them are real portraits painted from life?

Among the first would be Pope Alexander VI (1492-1503), part of the infamous Borgia dynasty. Less famous was the artist, Cristofano dell’Altissimo. The style of the painting is a bit clunky, but it shows off handsomely the red ermine-lined attire that became official papal portrait-wear until the mid-20th century.

Alexander VI’s successor, Pius III, only lived for a month after being elected. There was no time for anything except a posthumous portrait. From this point onwards, the greatest masters of the Renaissance stepped in to create the most renowned series of paintings of world leaders that has ever been seen. Papal images by artists such as Raphael, Titian and Velazquez have been such an inspiration that even atheists of the 20th century have fallen under their spell. Francis Bacon made history six years ago by becoming the world’s most expensive artist at auction. Much of his work is based on reinterpreting papal portraits with a nightmarish twist.

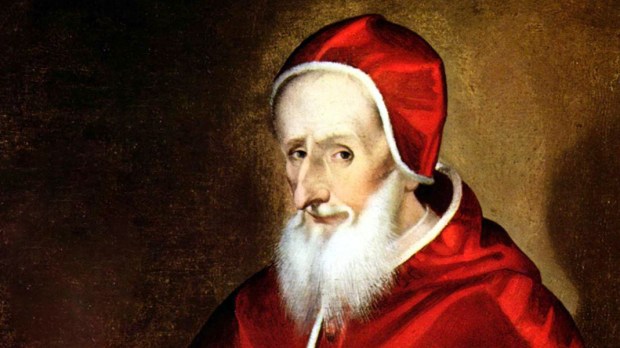

The original Renaissance artists didn’t need any shock factor to give their sitters more presence. Even an artist as gentle as Raphael was able to hint at the true character of the aged Pope Julius II. The drooping posture and long white beard don’t hide the steely resolve of a pope who chose his pontifical name in honor of the power-hungry Julius Caesar.

As with all the other Renaissance popes, Julius II wears red with a hint of white and is seated at a time when many sitters would strike almost any pose other than sitting. This was a pope who cared deeply about aesthetics, though. His crowning glory was commissioning Michelangelo to paint the Sistine Chapel.

Dozens of popes followed Julius II in having their portraits painted by leading artists of the day. There were exceptions. The fearsome Paul IV went further than shunning celebrity portraitists; he covered nude statues at the Vatican, ordered Michelangelo to repaint offending parts of the Sistine Chapel, and declared: “Even if my own father were a heretic, I would gather the wood to burn him.”

In comparison, Pope-after-next Pius V is positively cheery as he appears to wave to the crowds in a painting by El Greco. The papal highlight is probably Velazquez’s Innocent X. This is widely considered to be among the most important portraits of anyone in history, by an artist who is usually ranked number one by other artists. Among the other contenders is Titian’s painting of Paul III, remarkable (and scandalous) for including the pope’s grandsons. The painting gives no indication of how these grandchildren came about – the product of his four illegitimate children – but it is a masterpiece of family togetherness.

Fifty years later it was the turn of Titian’s heir, Caravaggio, who painted Pope Paul V. Unusually, on this occasion it was the pope who lasted a long time and the artist who quickly disappeared. The date of the portrait was not recorded but must have been between 1605, when Paul V was elected, and 1606 when Caravaggio fled Rome on suspicion of murder.

Papal portraits became rather formulaic from this point onward. Still, it was a formula that even a radical anti-clericalist such as Jacques-Louis David was happy to oblige. David was happier painting leaders of the French Revolution, such as Marat murdered in his bathtub. His favorite subject of all was the Emperor Napoleon. His official painting of Napoleon’s coronation, in 1804, shows the new emperor sidelining Pope Pius VII as he crowns himself and his wife while the Holy Father looks on. Napoleon must have felt some guilt, as a year later he commissioned David to do a portrait of a reflective Pius VII.

After David it was no longer the great names of painting who took on these commissions. The results don’t appear in the same surveys of “great art” that brim with the resplendence of Renaissance popes. The old formula clung on to despite the lack of critical acclaim. Right up to the mid-20th century, the official image of seated popes, wearing red, was maintained. A change only became really visible with St. Paul VI. From then on, the images that we are familiar with begin to feature far more white than red.

Art historians often say that white clothing is the supreme challenge for an artist. As 20th-century papal portraits are almost all in photographic form, we won’t know what modern painters are capable of. It’s clear that modern popes prefer to be seen in white. Is this because it is a more spiritual-looking color, or is it about putting distance between themselves and popes of the distant past? Those Renaissance pontiffs may have had the best artists, but few of them were the best human beings. Only one of them was made a saint (Pius V), and he is still reviled in England for excommunicating Queen Elizabeth I and worsening the fate of English Catholics.