Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

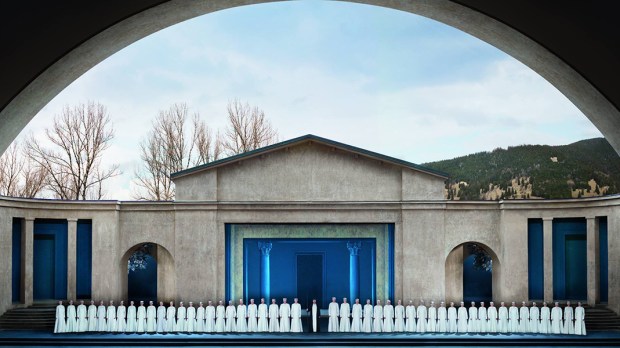

The Passion Play of Oberammergau takes place in the Bavarian village of the same name every 10 years. The play, performed over several months, dates to 1634 and draws hundreds of thousands of tourists from all over the world.

The performance began as a vow of the townspeople in response to the threat of a plague epidemic: if God would spare them, they would continue to act out the play every year. Nevertheless, the Oberammergau Passion Play is part of a long line of public religious performances dating from medieval times.

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, mystery and miracle plays developed among Christian nations at the end of the Middle Ages. Mystery plays are from the 15th century. Before this period dramatic pieces were called “plays” or “miracles.”

The art form originated in church itself. On certain solemn feasts, such as Easter and Christmas, priests dramatically depicted the religious event being celebrated, the encyclopedia explains. “At first the text of this liturgical drama was very brief, and was taken solely from the Gospel or the Office of the day,” it says. “But by degrees versification crept in. The earliest of such dramatic ‘tropes’ of the Easter service are from England and date from the 10th century.”

In time, the plays began to be performed in the vernacular, rather than in Latin, left the church and ceased to be liturgical.

One could say this was an early form of “taking the Gospel to the streets.” It was certainly a way for the masses, many of whom were probably illiterate, to learn the faith. Topics could be any period of salvation history, from the fall of man to the Apocalypse. And naturally, inventiveness and poetic license crept in.

The “mystery” plays that were popular during the 15th century often took up stories of the Old or New Testament or individual saints as their subjects. The word mystery is derived from the Latin ministerium, meaning “act,” not the mysteries of Christian belief.

“The most celebrated of these were the passion plays,” the Catholic Encyclopedia relates. Dramatic associations, such as the “Confrerie de la Passion” in Paris, were formed in large towns for the purpose of staging them. Being part of it demanded sacrifices.

“To play [the Passion Play], they condemned themselves to a labor to which few of our contemporaries would care to submit,” the encyclopedia says. “In some ‘passions’ the actor who represented Christ had to recite nearly 4,000 lines. Moreover, the scene of the crucifixion had to last as long as it did in reality. It is related that in 1437 the curé Nicolle, who was playing the part of Christ at Metz, was on the point of dying on the cross, and had to be revived in haste. During the same representation another priest, Jehan de Missey, who was playing the part of Judas, remained hanging for so long that his heart failed and he had to be cut down and borne away.”

Concludes the Encyclopedia, “And what the spectator saw represented was not fiction, but the holy realities which from his childhood he had learned to venerate. What was put before his eyes was most calculated to affect him, the doctrines of his faith the consolations it afforded in the sorrows of this life, and the immortal joys it promised in the next. Hence the great success of these religious performances. The greatest celebration a city could indulge in on a solemn occasion was to play the Passion.”

The York Mystery Plays, based on 15th-century scripts, are performed from a wagon in the city’s streets. Watch this performance from 2018.