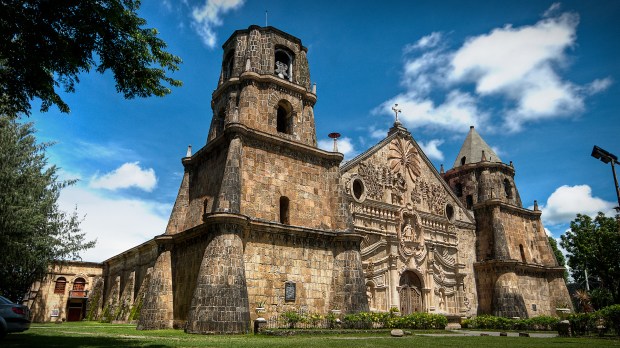

The Miagao “Fortress” church is one of the famous four great Baroque Spanish-era churches of the Philippines, the other three being San Agustín Church in Manila, Nuestra Señora de la Asunción in Ilocos Sur, and San Agustín Church in Paoay. While all of them were collectively declared UNESCO World Heritage Sites on December 11, 1993, there is something unique about the Miagao Church (also known as the Santo Tomás de Villanueva Parish Church): it is, at the same time, a church and a kind of fortress.

Read more:

In the Philippines, the soon-to-be tallest statue of the Virgin Mary in the world is about to be ready

The church’s foundation runs six meters deep into the ground, and its one-and-a-half-meter thick walls are reinforced with 4 meter-thick buttresses. As the original of town of Miagao was constantly invaded by the “Moros” for almost a decade in the mid-18th century, it had to be moved to a more secure place, so a new fortified church was then built at the highest point of the town to guard against potential invaders. But there is something else that makes this church even more special: its unique ochre color.

Built using a combination of Spanish Baroque and Romanesque Early Medieval architectural styles, with the addition of Chinese, Muslim, and local Filipino elements in the decoration of its façade (for instance, St. Christopher is represented in traditional Filipino attire, and the decorations of the bas-reliefs include papaya and palm trees), the Miagao Church’s distinctive yellow-ochre color comes from the inclusion of coral (ground into dust) and egg whites in the mixture for the adobes. In fact, the Spaniards customarily used egg whites to make mortar (“argamasa”) for their churches, in order to make the mixture more durable.

Read more:

Visit the great Baroque churches of the Philippines

Interestingly, the egg yolks were not discarded, but often used to make some of the most famous Spanish convent sweets and pastries, like the Yemas de Santa Teresa.

Read more:

5 Monasteries keeping ancient monastic recipes alive