Earlier this year, Pope Francis announced that documents in the Vatican Secret Archives relating to the wartime pontificate of Pope Pius XII will be open to scholars in 2020.

Why are the archives called “secret”?

In spite of its name, the Secret Archives are not secret. Rather, the word from the Latin title Archivum Secretum Vaticanum (or the Italian Archivio Segreto Vaticano) indicates that the archives are the “personal” records of the pope.

According to the website of the Archives themselves, Pope Paul V implemented a project to build a “Novum Archivum” in 1611. Situated in the Apostolic Palace, it collected registers and volumes from the Vatican Library, the Apostolic Chamber and the Castel Sant’Angelo Archives, and the Archivum Vetus, in the Paoline Room adjacent to the present-day Sistine Hall of the Vatican Museums. The Castel Sant’Angelo Archives continue to house the oldest, most precious documents of the Holy See, carefully stored in wooden armaria and arranged geographically.

The “official history” of the Secret Archives dates back to 1612, when Paul V appointed Baldassarre Ansidei, former custodian of the Vatican Apostolic Library, custodian of the new archives.

Over the next couple of years, the documentary material collected by Paul V would be housed in the three rooms on the piano nobile in the present-day Archivio Segreto Vaticano, next to the Sistine Hall of the Museums.

In 1630, Pope Urban VIII granted the Archivio Segreto Vaticano autonomy from the Apostolic Library, and in 1660, Pope Alexander VII assigned the floor above the three Paoline Rooms to the Archivio Segreto Vaticano and set it aside for the conservation of the Secretariat of State Archives.

Napoleon raids the archives

The archives underwent a great disturbance in 1810, when Napoleon Bonaparte seized the papal archives and transferred them to Paris. “About 3,239 cases or baskets of documents from the Archivio Segreto Vaticano and other archives of the Roman Curia left Rome on enormous wagons,” the website says. It wasn’t until 1816 that documents began coming back to Rome.

Several convoys transported back to Rome the rest of the documents Napoleon had seized from the Holy See and transferred to Paris. The high transport costs involved prompted the papal commissioners to destroy hundreds of documents that were considered “useless” and to sell thousands as wastepaper. Many documents belonging to the archives were lost in transit, and some papers and documents were delivered to the wrong place and did not end up in the original archives.

Pope St. John Paul II’s bunker-like storerooms

In 1881, Pope Leo XIII opened the doors of the Archivio Segreto Vaticano to scholars of all faiths from all nations, and 99 years later, Pope St. John Paul II inaugurated new storerooms under the Cortile della Pigna of the Vatican Museums, where documents could be protected in bunker-like conditions.

So what’s in the archives?

Plenty. There’s Pope Leo X’s 1521 decree excommunicating Martin Luther, a parchment that changed the course of history, as it ignited the Protestant Reformation.

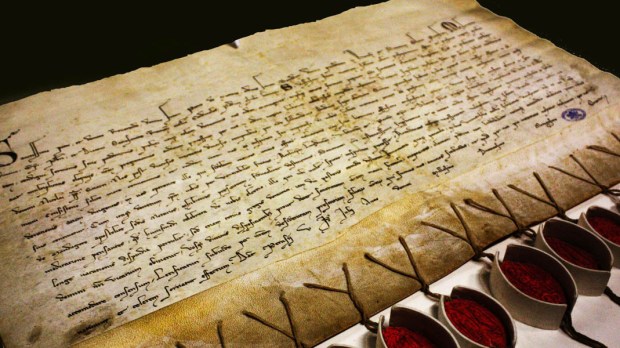

There’s a 1530 petition from 85 English clergymen and lords that asks Pope Clement VII to annul King Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon. According to Michael O’Loughlin, writing in Crux, the seals of many of the signatories were affixed to the petition, each held in place by red ribbon. “This is considered the source of the term ‘red tape,’” O’Loughlin writes. “Clement refused, of course, leading to the establishment of the Anglican Church.”

There’s a letter from Michelangelo to the pope, warning that Vatican guards had not been paid in three months, and that they were threatening to walk off the job.

There’s a bull (decree) from 1493, by which Pope Alexander VI divvied up the newly-discovered Americas between Spain and Portugal.

O’Loughlin continues:

- There are letters from Abraham Lincoln as well as Jefferson Davis, who wrote to try to convince Pope Pius IX that the South was an innocent victim of Northern aggression. Neither man was Catholic.

- The doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, the notion that Mary was conceived without original sin, was articulated in 1854 on a piece of parchment that’s in the archives.

- Famous Vatican trials were recorded with handwritten transcripts that are housed there, including cases against the Knights Templar in the early 14th century and astronomer Galileo Galilei in the 17th, who was tried by the Vatican for heresy and forced to spend the rest of his life under house arrest.

- When Sweden’s Queen Christina abdicated in 1654, she converted to Catholicism from Lutheranism, moved to Rome, and today she is one of the few women buried in St. Peter’s Basilica. There’s a letter to the pope announcing her conversion.