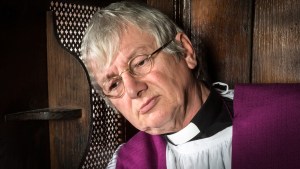

The archbishop of Melbourne isn’t expected to make further comment on the mandatory reporting law that has passed Victoria’s legislature, having already said that he is urging the government to focus on measures that will actually bring about greater protection for children and noting that legislators seem to be unaware of how the Sacrament of Confession works, since priests don’t normally know the identity of the penitents, and thus couldn’t report them to authorities.

On Tuesday, the state parliament passed laws that would carry a sentence of up to three years for priests who fail to report penitents who confess child abuse. Premier Daniel Andrews admitted the “most important thing” about the legislation is to “send a message.”

The Australian Capital Territory has a similar law, passed earlier this year.

Archbishop Peter Comensoli has already noted that if the government really wanted to protect children, the 2017 Royal Commission investigation recommended some effective measures, such as training to recognize and prevent abuse.

He’s also assured that “personally, I’ll keep the seal [of confession].”

Read more:

The seal of confession: What it is and why it should be protected

Archbishop Comensoli released a statement in August explaining why the legislation is unworkable. He first explained what the Church in Melbourne has instituted to protect children, and also his support for “religious ministers holding mandatory reporting responsibilities, a change the Catholic Church proposed in 2013.”

Read more:

Mandatory reporting laws and Seal of Confession not mutually exclusive, says Melbourne archbishop

But with this commitment to child protection, he assured, “I will also uphold the Seal of Confession.”

He explained that violating the seal would not address any of the needed reform, and that simply, “what is proposed is unworkable.”

It shows a significant lack of understanding about the act of Confession – particularly ignoring the anonymity of this sacrament, and the very real expectations of Catholic families that clergy will respect the strictest confidentiality of the Seal of Confession. Unlike a patient’s relationship with their doctor or psychologist, or a student’s relationship with their teacher, the relationship within the sacrament is between the penitent and God, with the priest being merely a conduit. It is a religious act, of a deeply spiritual nature, in which the priest has no latitude to require a penitent to identify themselves.

Despite the impracticality of the legislation, Australia’s is not the only government moving to enact it. Earlier this year, the US state of California considered something similar, though eventually withdrew the proposal.

At that time, Auxiliary Bishop Robert Barron of Los Angeles pointed out the impossible position in which such laws place priests, and also raised the concern that there will be some who undoubtedly try to take advantage of the legislation to trap priests:

I would like to make clear what the passage of this law would mean for Catholic priests in California. Immediately, it would place them on the horns of a terrible dilemma. Since the canon law of the Church stipulates that the conscious violation of the seal of confession results in automatic excommunication, every priest, under this new law, would be threatened with prosecution and possible imprisonment on the one hand or formal exclusion from the body of Christ on the other. And does anyone doubt that, if this law is enacted, attempts will be made to entrap priests, effectively placing them in this impossible position?

Read more:

Barron: It’s time for Catholics (and all religious people) to wake up to the danger of the California Confession bill

The seal of confession has accompanied the evolution of Confession from when it was public in the earliest centuries of the Church to its gradually becoming a private sacrament.

Read more:

Martyrs of the secrecy of Confession: How many beatings would he take?

Read more:

Martyrs of the secrecy of Confession: Would one priest betray another?